Miguel Díaz-Canel Becomes New President Of Cuba

Cuba has a new President and he isn't named Castro, but that doesn't mean we're going to see significant change in the near future.

For the first time in more than forty years, the President of Cuba will not be named Castro:

HAVANA — Cuba’s National Assembly on Thursday officially confirmed 57-year-old as Cuba’s new head of state, ending Castro rule after nearly 60 years and shifting power toward a younger generation born after Cuba’s revolution.

Walking next to Raúl Castro — the 86-year old who took over from his brother Fidel Castro in 2008 — Díaz-Canel entered the assembly hall in a dark suit and red tie to a standing ovation.

Díaz-Canel’s name was put forward Wednesday as the sole candidate to head Cuba’s council of state, a post that effectively serves as the presidency. On Thursday, officials announced the results of the vote: 603 to 1 backing his nomination as Cuba’s new leader.

Díaz-Canel’s selection amounts to the dawn of a new era in a country deeply identified with the Castros, who led the revolution that triumphed in 1959 and resulted in the most enduring communist system in the Western Hemisphere.

But Díaz-Canel, a consensus-builder, is almost sure to make decisions in concert with the country’s communist brain trust. As the country’s first vice president since 2013, he was wary of the thaw in relations with the United States under then-President Barack Obama and has tended to echo concerns that economic change should not occur abruptly.

In his inaugural speech, Díaz-Canel paid homage to the Castro brothers, Raúl and Fidel, as well as “the historic generation” of older revolutionaries who have run Cuba for the decades.

He vowed to bring “continuity to the Cuban revolution,” and to involve Raúl Castro “in the process of making the most important decisions to the future of the nation.”

He talked of cautious change, but always in the context of Cuban socialism.

‘There is no room for those who aspire to a capitalist restoration,” he said. “We will defend the revolution and continue to perfect socialism.”

Under Raúl Castro, considered more reform-minded than his long-ruling brother, Cuba has cautiously tested greater economic and social freedoms, often taking two steps forward and one step back. It will be up to Díaz-Canel to balance two realities: the need to respond to Cubans’ growing frustration over economic stagnation and the reluctance of the Communist Party to embrace faster reforms.

His touchstone, analysts say, will remain Raúl Castro — who will keep the influential job of head of the powerful Communist Party.

“You can look at Raúl Castro and Díaz-Canel as mentor and disciple,” said Carlos Alzugaray, a former Cuban diplomat.

The son of a mechanic, Díaz-Canel was born in the central province of Villa Clara. He became an electronics engineer at the Central University of Las Villas before joining Cuba’s Revolutionary Armed Forces. Afterward, he was a college professor and built ties to the Communist Party.

In 1987, he was assigned to be a liaison to Nicaragua, whose leftist Sandinista government received significant aid from Cuba. Díaz-Canel worked his way up to party secretary in his home province during Cuba’s “special period” in the early 1990s, when the collapse of the Soviet Union resulted in a cutoff of subsidized oil and an economic crisis.

He developed a reputation as an approachable, efficient manager who held impromptu front porch meetings in shorts and T-shirts. He also showed something of an independent streak — resisting party pressure, for instance, to shut down a newly established meeting place for gays and lesbians in his province.

In 2013, when he was education minister, Díaz-Canel intervened in a dispute involving a group of professors at Cuba’s University of Matanzas. They had started an independent blog — La Joven Cuba (Young Cuba) — offering critiques and commentary on Communist Party policies and personalities.

After their site was blocked on the university servers, a request came in to the professors. Díaz-Canel wanted to meet them.

“We had big speeches prepared, about how our blog was valuable to Cuban society,” said Harold Cárdenas, one of the professors. “But then, when we got there, [Díaz-Canel’s] first words were, ‘What do you need to keep doing what you do? And how can I help?’ ”

Cárdenas is now among those who see Díaz-Canel’s new role as a chance for measured change in Cuba.

“In the 1990s, he was one of the first Cuban leaders using a laptop, and now you see him using his tablet,” he said. “I do think Díaz-Canel can bring change, while also keeping continuity” in the system.

Still, Díaz-Canel’s position on freedom of expression may have hardened in recent years.

A video leaked last year, for instance, shows Díaz-Canel in a party meeting, threatening to block a website for acting “against the revolution.”

Since the video leaked, journalists at the site singled out by Díaz-Canel — OnCuba, a Miami-based outlet with offices in Havana — say they have received no official pressure to change their middle-of-the road editorial line. But the outlet has been the subject of attacks from pro-government bloggers, attacks that have served as a kind of message.

“We speak of Fidel as a man, not as a god, and of the Cuban community in Miami as being people who are not totally against this island,” said Mónica Rivero, editor in chief of OnCuba. She continued: “But it’s not really about us. It’s more about whether you can or can’t have this kind of change when it comes to expression . . . . Díaz-Canel is going to be in the shadow of Raúl and those who fought with Raúl and Fidel.”

Yet with new leadership, Cuba is indeed changing. The list of names presented for Cuba’s Council of State, which Díaz-Canel is set to head, notably excluded José Ramón Machado Ventura — an arch-conservative who fought in the revolution with the Castro brothers.

The new candidates also included the first black Cuban to hold the post of first vice president, and three female vice presidents. The results of the assembly vote are to be announced Thursday, but there is little doubt that those on the list will be approved.

All of those named to the powerful council are party loyalists. But their relative youth — the list includes Yipsi Moreno, a 37-year old former Olympic hammer thrower — suggested a passing of the torch.

“It’s very significant. It shows that Raúl has been successful in bringing into retirement much of the octogenarian group,” said Arturo Lopez-Levy, a former Cuban government analyst who is now a professor of political science at University of Texas Rio Grande Valley.

The New York Times has a profile of Cuba’s new President:

HAVANA — As soon as Cuba and the Obama administration decided to restore diplomatic relations, decades of bitter stagnation began to give way. Embassies were being reopened. Americans streamed to the island. The curtain was suddenly pulled back from Cuba, a nation frozen out by the Cold War.

But one mystery remained: While nearly everyone knew of Cuba’s president, Raúl Castro, his handpicked successor, Miguel Díaz-Canel Bermúdez, was virtually unknown.

So when a delegation of American lawmakers visited Cuba in early 2015, they peppered Mr. Díaz-Canel with questions: What did he think of the revolution that defined the island’s politics and its place on the world stage?

“I was born in 1960, after the revolution,” he told the group, which was led by Representative Nancy Pelosi, according to lawmakers in the meeting. “I’m not the best person to answer your questions on the subject.”

Mr. Díaz-Canel, who became Cuba’s new president on Thursday, has spent his entire life in the service of a revolution he did not fight.

Born one year after Fidel Castro’s forces took control of the island, Mr. Díaz-Canel is the first person outside the Castro dynasty to lead Cuba in decades.

He took the helm of government on Thursday morning to a standing ovation from the National Assembly, which elected him in a nearly unanimous vote. Mr. Castro embraced him, lifting the younger man’s arm in triumph.

Mr. Díaz-Canel’s slow and steady climb up the ranks of the bureaucracy has come through unflagging loyalty to the socialist cause — he “is not an upstart nor improvised,” Mr. Castro has said — but he largely stayed behind the scenes until recent years.

Now, as leader, Mr. Díaz-Canel is suddenly taking on a difficult balancing act. Most expect him to be a president of continuity, especially because he arrives in the shadow of Raúl Castro, who will remain the head of the armed forces and the Communist Party, arguably Cuba’s most powerful institutions.

But Mr. Díaz-Canel also has to figure out how to resuscitate the economy at time when President Trump is stepping back from engaging with Cuba. On top of that, Mr. Díaz-Canel must find a way to manage the frustrations of a Cuban population impatient with the pace of change on the island — without the heft of his predecessor’s revolutionary credentials.

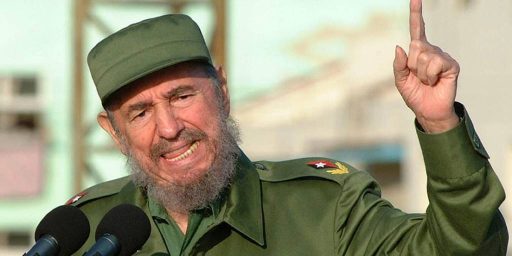

Such credentials have been the bedrock of political power in Cuba ever since Fidel Castro seized control of the nation in 1959. In the ensuing years, the Castros ruled over Cuba with ironclad control, bolstered by a cadre of loyalists, nearly all of whom had fought alongside them in the revolution.

In the end, the most effective opposition to the Castro brothers was time.

Fidel Castro handed power to Raúl in 2006, then died 10 years later at the age of 90. Raúl then ushered in some of the most substantial reforms in decades, and is now orchestrating yet another one — the passing of the torch to a new generation.

After opening up the economy to private investment and entrepreneurialism, expanding travel in and out of the country and re-establishing ties with the great enemy, the United States, Raúl Castro has selected Mr. Díaz-Canel to fill his shoes.

Despite recent efforts to raise his profile, Mr. Díaz-Canel remains a somewhat unknown figure both domestically and abroad. In 2012, he led the Cuban delegation to the London Olympics and accompanied Raúl Castro to an international conference in Brazil.

Still, “he is someone who has very little exposure to U.S. political or cultural figures,” said Daniel P. Erikson, a former State Department official. “He is simply not a known figure in the U.S., and frankly he isn’t that well-known in the rest of Latin America, either.”

Ever since Mr. Díaz-Canel was named first vice president in 2013, Cubans and Cuba watchers alike have scrambled to find out more about the enigmatic heir apparent, combing through his track record as party leader in the provinces of Villa Clara and Holguín, and later as minister of higher education, for clues on how he will lead.

In each position, according to those who knew him at the time, Mr. Díaz-Canel has been a quiet but effective leader, often with a progressive bent. Many called him a good listener, while others described him as approachable, free of the rigidness and inaccessibility of typical party chiefs.

Through it all, he has also been a relentless defender of the revolution and the principles and politics it brought.

(…)

But in Cuba, the continuum of political thinking is not black and white. Often, conventional definitions of progressives versus hard-liners do not apply. Leaders can be both, and Mr. Díaz-Canel is an example of that. While he is seen as open to the ideas of others, as a younger man he led a campaign to stifle students who read and discussed literature that was not approved by the Communist Party, according to those who knew him at the time.

Last year, a video was leaked of Mr. Díaz-Canel addressing a group of party officials. In it, he lambastes the United States, claiming that Cuba had no responsibility to meet its demands under the reconciliation brokered by President Barack Obama.

He then went on a diatribe against a website whose work he considered subversive. He told fellow officials that the government would shut it down — no matter whether people considered it censorship.

The video was seen as a way for Mr. Díaz-Canel to shore up his credentials with hard-line factions within the government, and yet a review of his career shows that he has not shied away from confronting activities deemed out of bounds by the government, either.

Prior to today, the office of the President of Cuba had been occupied by a Castro since 1976 when Fidel Castro was appointed to that position. Prior to that point, there had been two Presidents in post-Batista Cuba, Manuel Urrutia Lleó, who served in the position for roughly seven months in the immediate aftermath of the revolution, and Osvaldo Dorticós Torrado, who served from 1959 until Casto assumed the position, During that period, of course, the real power in the country was in Castro’s hands as head of the Cuban Communist Party, and this seems likely to be the case at least initially for Diaz-Canal given the fact that Raul Castro will retain his title as head of the Communist Party and will thereby continue to hold some influence over the direction of the country. Castro, however, indicated today that Diaz-Canel is likely to assume his position as head of the Communist Party at some point in the future although it’s unclear when that might happen. As things stand, the younger Castro is 86 years old but appears to be in good health so he may decide to hold on to power for some time to come, and Diaz-Canel seems to be a Castro loyalist who would be unlikely to try to push him out of office. Notwithstanding the fact that Castro will remain, in some sense, the power behind the throne the fact that the Castro family will be out of power marks a significant change for Cuba that could have an interesting impact going forward.

Diaz-Canel’s appointment comes amid several changes that have impacted Cuba in the years since Fidel Castro handed over most of his power to his younger brother. While maintaining party rule and the repression that comes with it, the younger Castro did preside over some liberalization in the economic area that was largely made necessary by the state of Cuba’s beleaguered economy and the fact that the nation could no longer rely on the economic assistance it used to receive from the Soviet Union during the Cold War. This has led to an increase in some foreign investment from Europe and elsewhere in the world that has helped improve the state of the economy. There has also been at least some lifting of the repression of news and information that typified the regime for much of its rule, although not to the full extent that Cubans ought to be entitled to.

Perhaps the biggest change under Raul Castro, though, came in 2014 when talks with the United States led to the first significant normalization of relations between Cuba and the United States since the Revolution. Those moves included the lifting of a part of the embargo that had been in place since the Kennedy Administration and liberalization of the reopening of mutual embassies for the first time in 54 years and the resumption of commercial air travel between the two nations. While there are many elements of the embargo against Cuba that remain in effect that can only be lifted by Congress, this has resulted in a significant uptick in travel between the two nations and the beginnings of American businesses exploring opportunities for investment in the island nation to compete with European, Chinese, and Canadian companies that have pursuing these opportunities for several years now. Finally, in March 2016 President Obama became the first American President since Calvin Coolidge to actually visit Cuba. Soon after taking office, President Trump rolled back some of the changes in policy toward Cuba that his predecessor had implemented, but not all of them, and the fact that a Castro will no longer be in power in Cuba could be a means to allow for more liberalization in a policy toward Cuba that has been outdated for decades. Whether Trump would get behind that effort, and whether Republicans would be willing to change the anti-Cuba rhetoric that they have relied on largely to help their political position in Florida, remains to be seen.

Notwithstanding the fact that someone other than a Castro will be the leader of Cuba this isn’t likely to lead to real change in Cuba in the short term, of course. As the profile above notes, Diaz-Canal has long been a strong supporter of the Communist Party and the revolution and seems unlikely to be inclined to roll back any of the political restrictions that have been in place in Cuba since the overthrow of Batista back in 1959. That being said, there’s no small degree of symbolic importance in the fact that Cuba is being handed off to a new generation of leaders and it will be interesting to see what impact that could have on the island nation’s future. For a wide variety of reasons, the idea of opposition to either of the Castro brothers was largely unthinkable but it’s unclear whether or not Diaz-Canal will be able to count on that kind of loyalty within the Communist Party, especially after Raul Castro gives up his position as head of that organization at some point in the future. In the short term, then, Cuba will remain much the same as it is today. Hopefully, though, there will be a brighter future ahead.

This translates to moving toward socialist institutions and away from state capitalist institutions, a process toward which there has been great resistance by the bureaucracy. My hope is they continue on that path rather than further empowering the red bureacracy with private capitalist reforms.

@Ben Wolf:

One of the things in one of the articles I linked to that I linked to but didn’t post noted that Fidel Castro had resisted efforts to build statutes or name buildings or stadiums after him or his brother. Apparently, he had concerns about the idea of a “cult of personality” developing around the Castros. It would appear he learned from one of the more significant mistakes the Soviets made under Stalin.

One has to wonder why Castro the not-so-younger chose not to perpetuate the royal bloodline on the throne.

@Doug Mataconis: I would hope that’s true. A lie as monstrous as the Soviet Union should at least do the good of teaching us lessons on what to avoid. China continues down that road but the Cubans, at least for now, are taking the libertarian path.

The new leader of Cuba needs to publicly repudiate communism as the failure and sham that it is.

@Tyrell:

Please share your shopworn spiel that Cuba needs to repay us before we graciously grant them our hard-earned Yankee tourist dollars. That bit is gold. I love that.

@Tyrell:

Your Cuba material isn’t as sharp as your Iran stuff, though.

It’s amazing when you bang away at them like 1979 happened yesterday and that Mohammad Reza Pahlavi was the popularly elected ruler and that the Mossaddegh coup d’etat never happened at all, let alone was a US /UK operation.

I really dig your take that they have to scrape and bow and beg for our forgiveness or else we’ll nuke them just on principle. That rocks so hard.

And so savvy. Exactly the type of clear-headed foreign policy analysis we need in this topsy-turvy world.