On the Evolution of SCOTUS

When life terms means almost three decades on the bench, fights will be fierce.

Constitutional law professor Richard H. Pildes has a guest post the Monkey Cage that is worth a read: Neil Gorsuch’s confirmation shattered political conventions. Here is why.

Constitutional law professor Richard H. Pildes has a guest post the Monkey Cage that is worth a read: Neil Gorsuch’s confirmation shattered political conventions. Here is why.

The headline is a bit off the mark, as the post is less about Gorsuch, or about shattering conventions, than it is about why the politics of nominations are as heated as they are.

First, the average tenure of a justice is much longer now. From 1941 to 1970, justices served an average of about 12 years. But from 1971 to 2000, they served an average of 26 years.

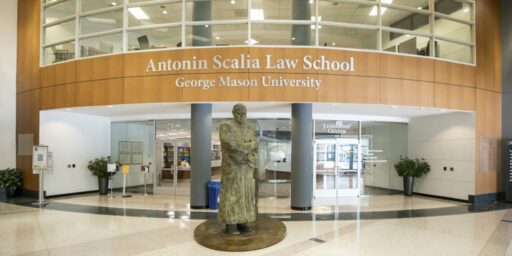

That figure has increased only since 2000. When John Paul Stevens retired from the court in 2010, he had served 35 years. When Antonin Scalia died, he had served 30 years. Anthony M. Kennedy has served 29 years, Clarence Thomas 26 years, Ruth Bader Ginsburg 24 years, and Stephen G. Breyer 23 years. Presidents who might serve only four years can have influence decades later if they can appoint someone to the Supreme Court.

[…]

Second, precisely because justices serve so much longer, vacant seats arise less often. From 1881 to 1970, a vacancy arose on average once every 1.7 years. But since 1970, a seat has become vacant only once every three years or so.

[…]

Third, the power of the Supreme Court has increased significantly. Over the 20th century, the court became more aggressive in declaring federal and state legislation unconstitutional. In the 1940s and 1950s, the court was invalidating about one act of Congress each year. In the 1990s, that number had become about four a year. Since 2010, it has been about three per year.

The piece is worth reading in its entirety.

And, as anyone who has read my posts on this general topic will not be surprised that I agree with the following:

The Supreme Court confirmation wars will become less heated only if the stakes in individual appointments diminish. One way to bring that about would be a constitutional amendment limiting Supreme Court terms to 18 years, staggered so that vacancies would occur at regular two-year intervals. Academic authorities on the Court and others have been floating versions of such proposals for years, but they have gotten little political traction. Absent change of this sort, the confirmation wars are likely to grow hotter.

And yes, before someone says it (as they always do when some kind of reform like this is mentioned): this is unlikely to happen. Nonetheless, I think it is worth trying to start a conversation on the topic, since that is the first step for potential change. I fully recognize that there is currently no scenario that would trigger such such a reform.

I would also note, for those who like to think about such things, that the way the Court is functioning is by no means how it was originally conceived (in a variety of ways). This is certainly true in the sense of the length of time that Justices are spending on the bench. This is worth noting if anything because one of the main reason we, as Americans, do not engage in constitutional reform is because of the mythology we attach to the perfection of the original constitution and the assumption that the Framers were transcendent in their ability to design institutions.

We shouldn’t forget Roe v. Wade which has politicized the court much more than would otherwise be the case.

@Andy:

I believe Roe v. Wade politicized ‘The People’ more than it politicized the Court.

@Andy:

Roe v. Wade likely has played a role yes, but it’s worth noting that there have been controversial and politically unpopular decisions from the Court in the past going all the way back to Marbury v. Madison.

@Andy: I don’t recall R v W being all that contentious at the time. IIRC the “right to privacy” was basically just doctor/patient privilege and the libertarian idea that it was none of the state’s damn business. It only became a big thing when the Falwell types realized they could fund raise off it.

This is not to dispute your point but to say that if there’s a villain in the piece it wasn’t the court, it was the holy roller preachers. And yes, that is the root cause, well a root cause, of our current politics. There are large numbers of people who will vote for any idiot

Leopards Eating FaRepublican as long as he promises to hate abortion.Indeed, evangelicals didn’t care much about abortion back in the day. The Religious Right’s initial organizing cause was to stop desegregation.

http://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2014/05/religious-right-real-origins-107133

@Andy:

Your comment has a nice beat and I’m sure that you can dance to it, but it doesn’t actually mean anything.

What important state interests were being protected when Texas banned abortions?

@Doug Mataconis:

Roe V Wade has exacerbated the factors in the article because it is the most important issue when it comes to SCOTUS confirmations. I also think Roe V Wade is important in a way that other decisions aren’t because abortion rights rest on the continued centrality of that case and abortion remains a very devisive issue.

I love how we’re talking about reforming the Court instead of acknowledging the reason the stakes are high in the first place. If Congress wasn’t hyper-partisan and willing to follow very obviously biased agendas, the Court wouldn’t have to intervene so damn much. Partisans want to pack the Court to get their way because they know the laws they pass won’t pass muster otherwise. Party should have nothing to do with decisions.

There’s nothing inherently wrong with Justices having longer terms since the search for Justices is supposed to yield quality and not formulaic party lines. People need to let go of the idea that parties or ideologies have “seats”; Scalia didn’t own his so there was no right to a conservative inheriting it as Republicans have been screaming for a year plus. That being said, watch that logic fall to the wayside if RGB dies. Suddenly, it won’t be a “liberal” seat that should be preserved to keep the balance but rather “winner calls it” with Trump nominating a conservative and the GOP gloating that Dems can do nothing about it. The Courts are now a tool of Congress’s agenda instead of being its own independent Constitutional arm.

One solution that some people have offered is the idea of increasing the membership of the Court in an effort to decrease the extent to which one appointment becomes so important. In the short term, that might just happen, but it wouldn’t last for long, and there’s only so far you can go in expanding the membership of the Supreme Court before you do something that would make it unmanageably large in the manner that many legal scholars argue the Ninth Circuit has become.

If this idea were considered it strikes me it would only work if certain criteria were met.

First, both current and retired Justices should be consulted for their thoughts on the impact that a larger membership might have on how the Court functions. Practically speaking, a Supreme Court that went beyond 11 members starts to look unmanageably large from my perspective, and the Justices who have served there would be the best source to speak to the practical limitations on Court operations such an expansion would create.

Second, if this were done Congress would have to find a way to ensure it doesn’t turn into an effort by whoever happens to be POTUS at the time to pack the Court with nominees. This is especially true in the new, post-nuclear option, world we are in after Thursday. Perhaps initially the appointment of new Justices to fill expanded seats could be spread out so that one President doesn’t get three or four appointments right off the bat.

The one advantage of this idea is that it would not require a Constitutional Amendment, merely a statutory change. At other points in our history the maximum number of Justices has been at different levels depending on the law was in effect, Between 1789 and 1869, for example, the number of Justices on the Court was as low as 5 and as high as 10, The last change came with the Judiciary Act of 1869 when the membership was set at a maximum of nine. Congress could change that at any time, although the fact that it has stood for nearly 150 years now suggests it’s unlikely Congress would agree to change it any time in the near future.

The Supreme Court became “controversial” when it began to recognize the rights of minorities.

The Supreme Court of the 19th century upheld segregation (Plessy v Ferguson) as it dismantled civil rights (the various cases re: the Civil Rights Act of 1875). These results were perfectly fine for the white majority that either didn’t care or else were hostile to equality.

The postwar Supreme Court took a different tact, tearing down Jim Crow institutions and the caste system that went along with them. They label that as “controversial” because they preferred the status quo of white supremacy.

Those folks still can’t get over it. They’re so upset that they restructured the party system from being largely urban v rural to pro vs anti civil rights. And the antis are crafty enough to recognize that the Supreme Court is one institution that can impede or aid their reactionary cause, which has led us to this.

@Pch101: I don’t think it was Texas’ interests that were being argued , but the right of a woman to not be obliged to carry a pregnancy to term was.

@Doug Mataconis:

Also, I’ve heard people talk about an age or a term limit, and that is an obvious recipe for political mischief/mayhem too. I could see one party trying to force the other to nominate someone who is older (say 65) to the court, figuring that 20 years on the court is better than the 40 you get when the nominee is 45 years old.

@Michael:

Roe v. Wade addressed a Texas law that had banned abortion.

@Doug Mataconis:

I’m super confused how adding justices to SCOTUS would make it unmanageable in anything like the way the 9th Circuit is challenged. I thought the 9th is difficult because of its large number of cases compared to the number of justices. SCOTUS needn’t take more cases if they had a 13 judge roster, I think, and they’re already maxed out on jurisdiction, so there’s no change there, either.

Would you say mre?

The Supreme Court judges need to send a lot of those cases back to the states. And many of those cases need be settled at the local level or let the people vote on it. Too many complaints are sent to the Supreme Court that do not involve the Constitution. One such example was the infamous and spurious ruling about the health care act.

The whole idea of a Federalism and of English Law implies that the Supreme Court is going to take a lot of cases from the states and Congress. That’s the meaning of the whole idea of institutions. If you are going to take a very closed and strict reading of the Bill of Rights you are going to end without any rights in the Bill of Rights.