Primaries and Party Evolution

Open access to party labels has consequences.

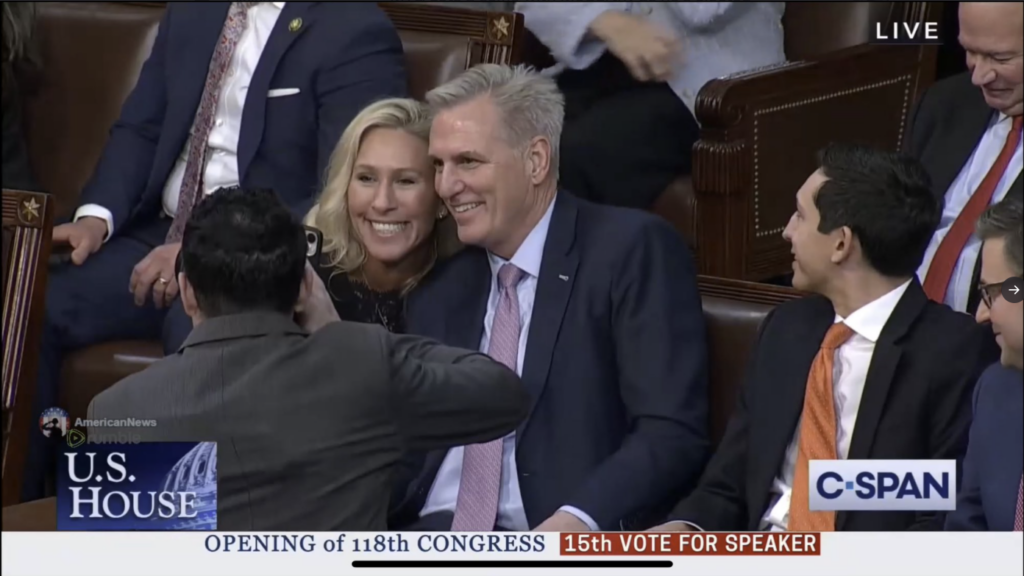

The above image, from the recent floor fight over the Speakership, is a fantastic illustration of my ongoing discussion of how primaries affect party evolution in the United States. The simplest version of the discussion goes as follows. Problematic Politician (PP) wins a primary. Winning the primary means using a major party’s label. Winning control of the label means the golden ticket to compete in the general election (It gets PP on the general election ballot automatically). If the district is dominated by the party label that PP won control over, the general election is a gimme. Of course, once the elected to be the incumbent member of Congress from that district, losing the seat becomes a low probability event.

This is an illustration of one key role played by parties in a representative democracy: the label is a signaling device to voters who use it often as the sole decision item in terms of their vote.

Once PP goes to Washington they are a part of their party’s caucus and no matter what else is true about them, the fact that they own their party’s label means they might be very important, especially if the party is in the majority and that majority is narrow. The assumption is that PP will be voting for the caucus’ desired leadership. Usually, this is mostly Pro-forma, but it is always possible that PP might need to be convinced to play. Maybe this means cutting deals, as McCarthy did with Matt Gaetz, a PP from Florida. At a bare minimum, it means normalizing PPs into the party caucus.

This is an illustration of another major role played by political parties in a representative democracy: they are collective actors, bound by label (as a sign of membership) to collectively organize the government.

Note, though, the utter lack of any centralized control of party labels in the United States. Control of a given label for an individual politician comes via the primary. Once in Congress, you are in the club and only truly extraordinary circumstances change that (as opposed to other democracies that we could name).

All of which sums to the following.

The more the party, as a whole, needs votes from the PP (or, as we saw in the Speaker fight, PPs) then more the party will have to normalize its more problematic members, hence mainstreaming them. This is clearly what Marjorie Tayle Greene wants and has achieved to some degree. It is what Matt Gaetz and Lauren Boebert are getting. At a bare minimum, they were central and important during that fight, even as they rebelled against the vast majority of the caucus.

Along those lines, see The Hill: Handful of McCarthy detractors get new top committee assignments

Four of the Republicans whose votes against House Speaker Kevin McCarthy (R-Calif.) led to a historic four-day Speakership floor fight last week will get new roles on top committees.

Rep. Byron Donalds (R-Fla.) and first-term Rep. Andy Ogles (R-Tenn.) will join the House Financial Services Committee, while Reps. Michael Cloud (R-Texas) and Andrew Clyde (R-Ga.) will join the House Appropriations Committee.

The general dynamic I am describing here also will be the reason the House GOP will treat George Santos (R-Narnia),* as a perfectly normal member of the chamber and make noises about “innocent until proven guilty” and “let the process work its way out” because they can’t afford to lose a seat with the slim margin they have in the chamber. McCarthy, in particular, is aware that he needs every vote he can get for, well, anything and everything the caucus attempts to do over the next two years.

And this is also how the party, as a whole, changes. If you are forced to normalize that Q-Anon types and the fabulists (as well as the election deniers and insurrection-downplayers), your overall organization evolves to adapt. To be clear, these types of changes don’t have to be in the PP kind of direction, the same dynamics apply to various possible directions, even the pragmatic. It all depends on what the nomination process produces.

This brings me to one of my core points about primaries. US parties are not constructed in a strategic way, but instead, evolve on the fly in response to whatever the primary process produces. And let me remind the reader that the vast majority of partisan office-holders come into the party, officially speaking (as in controlling the label) via the primary process.** The press has a tendency to pretned like it is jus the presidential nomination process, and I find sometimes that that is therefore where readers’ minds go. The entirety of the party system is shaped by primaries, and have been for a very long time (longer, by many decades, than has been true about presidential nominations).

There are no gatekeepers for control of the label, save the primary voters. Moreover, those gatekeepers tend to be a relatively small slice of the electorate, tend to be ideologically more extreme than the general pool of co-partisans in a given district, and they operate in a low-information environment (especially if it is an open seat).

I would refer readers back to my post in June of 2020, QAnon and Congress, which discussed how MTG won the nomination and was certain to win the seat (and I will confess to being mildly surprised that she has only been in Congress since 2021. It feels so much longer than that–I was thinking 2019, TBH). Greene was one of nine candidates in the primary and she had the most money of any of them.

As I wrote at the time,

My basic point remains that we do not have a system that allows for the coherent construction of political parties that can cogently present policy alternatives to the voters. Instead, we have two vessels that can be filled in various ways without national strategic purpose. The gateway to running in a primary is self-selection and nothing more. The only way to filter out fringe candidates is to hope that primary voters are savvy enough to do so in what amounts to massive collective action problem.

And if the fringe candidate is the one with the most money and therefore the most name recognition, then that fringe actor can capture control of the party label, whether the party writ large wants that candidate or not. And then, from there, the partisan breakdown of the district is destiny save in very unusual (if not impossible, depending on the numbers) circumstances.

None of this, by the way, is a defense of the House GOP caucus embracing Matt Gaetz, MTG, or George Santos, but it is an explanation of how the party ends up behaving as it does. And how any party in the US is likely to behave given the conditions above (slim majority, internal conflict, etc.).***

Not only do these dynamics influence the internal party behavior in the chamber, but it also affects what voters are socialized to accept. If their team is embracing certain PPs, it makes it easier for the general electorate to also accept those PPs and any others that might emerge. It changes what is “normal” for a given set of politicians and their voters.

That last point is really, really important. In an alternate universe, MTG would have been the QAnon candidate running against a mainline Republican and a mainline Democrat. She would likely have lost the election in 2020 as a result, because having to openly discuss her views without the cloak of protection of the Republican Party would likely have turned a lot (but not all) of voters off. And while partisans can jump ship (as we saw in Boebert’s slim re-election win), it is always better to be the major party nominee because a lot of voters use that as the main signaling device for voting. And when the fringe gets into office, those voters often will simply become more accepting of the fringeyness of it all, rather than reject their team.

Some additional writings on this subject:

- The Centrality of Nominations

- The Power of Primaries

- A Note on Primary Elections

- An Extreme Example of the Problem with Primaries

- Another Example of Primaries in Action

- Assessing the Party Fringes

*This is especially true because if Santos is kicked out or resigns, there is a very high probability he will be replaced by a Democrat because of the partisan makeup of his district. This fact, coupled with the slim majority, means Santos is safe from internal attack unless something truly indefensible is revealed (and note that the threshold for what they might be is defined by the circumstances I have outlined).

**I would note that in states with Top Two access to the label in the first round is basically all-comers, the same in Alaska’s Top Four process.

***And yes, a thousand times yes, the GOP is responsible for whom it embraces and what it ignores. But that responsibility doesn’t change that our overall system helps to produce it and that all of us have to live with the consequences thereof. I know someone is going to assert that the GOP is inherently susceptible to these outcomes and the Democrats aren’t. I think this is both true (as it pertains to certain specifics) and not true (as it pertains to the fact that any party under the right conditions can be held captive to a fringe), but that doesn’t change the overall analysis. Indeed, we can see how Senate Democrats had to kowtow to their moderate fringe (if you will) when it came to Kirsten Sinema and Joe Manchin.

Further, I have made clear that I see the GOP’s fringe as a different animal than the Democrats’. See Not Both Sides wherein I noted, apropos to the above, “Kevin McCarthy is about to be Speaker because he kowtowed to Trump and he is about to have to placate people like Marjorie Taylor Greene and Lauren Boebert in the process.”

What you say is completely true, but it’s worth pointing out that primaries aren’t the only reasons that bad behavior is normalized and a parties character becomes fundamentally changed. The Southern Strategy was crafted before the primacy of primaries, in smoke filled rooms among party bosses, but it has had a profound effect on the party.

@MarkedMan: Actually, and to the point of an aside in the post, primaries were a tool of segregationists in the early 20th Century.

See, for example, “white primaries.”

And the reason many states (like Alabama and Georgia) have majority run-offs in the primaries is because it dilutes the voting power of Blacks.

But, I will certainly agree that primaries aren’t the only reason parties accept bad behavior.

Reading this and Dr. Joyner’s airline piece one after the other, I cannot help but think that America excels at finding ways to race to the bottom.

There’s a lack of minimum acceptable standards, and a broad belief that things will somehow work out despite all evidence to the contrary. There’s not enough of a negative feedback loop for things to work out in the end.

Swing district Republican-aligned voters don’t reject their local Republican candidates because they’re willing to caucus with the Q folks. Airlines don’t face enough of a consequence when things go wrong to cause them to build in more buffer into the system so failures don’t cascade. The market doesn’t correct.

Ladies and Gentlemen, today’s Republican Party:

Only 41% of GOP voters think MLK day should be a Holiday. That’s 9 points lower than when the holiday was enacted in 1983.

https://www.mediaite.com/news/shock-poll-only-41-percent-of-republicans-say-mlk-day-should-be-federal-holiday-7-pts-less-than-when-law-was-signed-in-1983-2/

https://docs.cdn.yougov.com/vkklxli0e8/econTabReport.pdf Page 147 for the crosstabs.

@Steven L. Taylor:

Can I fully accept your overall analysis and still wonder why the asymmetry of these outcomes as they pertain to Democrats and Republicans might help us better manage this political moment? There has to be some useful understanding to come from this moment when The Four Whackjobs of the Apocalypse hold sway in the GOP, while the Most Problematic Politicians on the Democratic side I could come up with are The Squad. (And a Whackjobs to Squad comparison isn’t apples to oranges so much as apples to bowling ball.)

I’m loathe to help the Republicans out of their current mess. But, what could they learn from how establishment Democrats have managed to minimize the real political power (as opposed to rhetorical influence) of their fringe during their primaries? And how they managed to do that despite the strong polarization in US politics today.

@Scott F.:

The first question to pose is “have they in fact” minimised their fringe or is it more that their fringe is simply weaker numerically than the mirror of it on the right side.

If – as would appear to be the case – the Left fringe is generally smaller numerically than its Right equivalent (and perhaps differently structured geographically in ways that are election district important), then you do not have a strong lesson as such from the Democrats, rather more a dodged bullet for now.

Regardless, the general take away from across an ocean is that the naive drive for ‘more democracy’ at the primary level has had a quite perverse effect (and undemocratic one in the end given the unrepresentativeness of the primary voters). Enabling better party machinery control would rather seem a better idea – perhaps more realistically achievable than other reforms….

@Scott F.: While I do think that Pelosi was a more skilled leader than McCarthy, I think the solution isn’t necessarily in anything the Dems have done specifically.

It may well be that the American right is more susceptible to this kind of fringe. I think that a combination of the Cold War, which tamped down isolation and some forms of xenophobia (e.g., it was ideologically more accepted to want immigration because it proved our system was desirable) and the weird one-party status of the deep South made it possible for some of those influences to be diluted.

It is also the culmination of decades of anti-governance rhetoric and infotainment approaches to politics.

How does RCV interact with primary voting? Or don’t we have enough data to say yet?

@Stormy Dragon: RCV as it is currently practiced on a limited basis in the US actually makes the party-weakening effects that I note in the post worse. It is what I am referencing in note #2 above.

Indeed, if we look at Alaska, the system basically allows anyone to use D or R in the initial round, meaning that there isn’t even really a primary (same is true of CA’s Top Two, which isn’t RCV, but has similarities to AK’s first round).

Further, any system that uses single-seat districts is going to have the same basic problem I keep discussion: the partisan lean of the district is the most important variable.

If you have an interest in this, I would suggest the work of Jack Santucci.

Now, if we shifted to RCV in multi-seat districts (also known as STV, the single transferable vote, as used in Ireland) then you have a system that produces much more proportional results than does our system.

But another way: nominations are how parties can control what their label means. Primaries (or any variation thereof) mean that it is ultimately up to the candidate what the label means.

This means parties can change without any central directive from the party as an organization. It also means that politicians have zero incentive to form new parties, since they have open access to already established party labels.

Why open a “Joe’s Burger Shack” when I can open a “McDonald’s” and get an already established customer base for the same cost?

@Steven L. Taylor: without I believe you mean (“with any central”)

Regardless, I take away that sans centralised control of the label at least the state level, the inevitable tendency will be as observed.

@Steven L. Taylor: it is perhaps the electoral geography effect you have, given the rural tendency to the right and those specific factors.

@Lounsbury: Indeed, “without”–thanks for the correction.

And yes, our electoral geography is a huge part of it (and the distortions in our politics that gives those areas outsized importance).

@Steven L. Taylor:

Does RCV tend to lead to more moderate or less moderate winners (relative to a primary/general election)?

@Stormy Dragon: The simple answer is that despite the claims made by RCV enthusiasts, there is no reason to assume that RCV will produce more moderate outcomes in and of itself.

The full answer requires more explanation, not surprisingly.

@Steven L. Taylor:

Right, that’s why I was asking. Is there data yet on the actual effects of RCV? If it weakens parties but leads to more moderate candidates, that might not be a bad thing as it would make compromise more likely, but it could also weaken parties and make candidates more extreme, which would be worse.

The main thing I guess I’m wondering is whether doing it all in one fell swoop as opposed to jungle primaries or runoff elections, does RCV offset the problem with only a small group of the most partisan people participating outside the general?

Another question: is their any data on primary participation rates by party? Are Republicans more likely to vote in their party’s primary or less?

Excellent post, I can’t find anything to disagree with, so I’ll add something that I think is under-discussed.

Specifically, as the parties have gotten weaker, the power of various leadership positions in government has gotten strong, principally the Presidency, but also the Speaker and Senate Majority Leader.

But the Speaker is perhaps the position that has changed the most in the last decade.

It was originally intended to be a quasi-administrative function to ensure the smooth running of the House. As partisanship came into the picture, it became more of a partisan position with the Speaker giving specific advantages to their side, but for a very long time the norm was to still about promoting good order in the body, including giving individual members, committees and the minority a voice, such as the ability to bring up amendments on the floor.

In the last couple of decades, probably starting with Gingrich, this all began to change. More rules were added – both formally and informally – that increased the power of the Speaker. In the last decade, the Speaker has become quasi-dictatorship, beginning with Ryan and then continued by Pelosi. Ryan finally ended regular order and that continued under Pelosi and mostly continues under McCarthy.

The end of regular order means the Speaker today controls the entire legislative process in the House, and nothing comes to the floor, and nothing is considered, much less passed, without the Speaker’s permission. The ability of regular members – from both the majority and minority – to offer amendments to legislation on the floor is no longer allowed. Any amendment that is offered must have the Speaker’s prior approval. Legislation no longer goes through the normal committee process. Instead, the Speaker, along with leaders of various factions within the House, determines the content of legislation in private, takes a secret roll call, and only brings it to the floor when passage is assured. The usual tactics are used to make individuals play along and accept whatever the leadership proposes.

The ultra-MAGA representatives in the GoP understand how this game is played, which is why they insisted on making a small step toward the return to normal order, such as the ability for members to propose amendments on the floor. Given the very tight margin the House, they have the ability to force the Speaker to accept some terms and they understand that they would be sidelined if the majority was larger.

That is both good and bad – good because a return to normal order is good and necessary for the proper functioning of Congress. A House whose agenda is entirely controlled by one member is, to say the least, highly undemocratic. But it isn’t good because these dispensations were, perhaps, only given to the ultra-MAGA people. I haven’t done the research yet, but hopefully, there are actual rule changes that need to be adhered to evening and not pinky promises to a handful of douchebag GoP House members. But, of course, such rules could be rescinded assuming they exist.

Anyway, from a systemic POV the power of the Speaker as it’s currently exercised is undemocratic and contrary to the intentions of the role. There is no good reason for one member to have such sweeping authority over the agenda of Congress (and the country), an authority whose only limit is what the Speaker’s partisan majority will accept. But we know from group dynamics that it would take a major fuck-up for a Speaker to be removed and replaced by the membership. There is a strong incentive for tribal loyalty, even if individual members don’t like that they have no real power.

All of Steven’s excellent discussions about primaries and weak parties have been key enablers of this shift. Since the only political threat to most members of Congress is a primary challenge, the incentives for those members are to avoid that. And you avoid that by being the “gray man,” not sticking one’s nose out, and voting with the group. And one important partisan role of the Speaker is to try to ensure that members never have to take a tough vote that will bring a primary challenge. The Speaker also coordinates so that vulnerable members can vote against something as long as the legislation will still pass. In short, the Speaker will allow members to vote against (meaning they won’t be punished) as long as they get enough votes elsewhere. And it’s also beneficial to individual members to be able to defer to leadership since they control the agenda and write the actual legislation. Note, for example, how a lot of moderate Democratic politicians in swing states refused to say anything about the BBB and had nothing about it on their website. Why take a stand and risk political vulnerability when it’s easier to stay silent and vote with the group?

In short, we’ve adopted many of the worst aspects of a parliamentary system, with none of the benefits.

The Senate isn’t there yet, but it’s moving in that direction, and individual Senators have de facto more power in the institution.

As time goes on, I’m more convinced that nothing will change without significant primary reform along with rolling back some of the well-intentioned reforms that weakened parties, particularly regarding campaign finance.

@Steven L. Taylor:

RCV isn’t a god-send, but I think you are selling it too short. RCV, in a strictly partisan contest, can prevent fringe candidates from gaining the nomination based on a small plurality. RCV in an open or top-2/top-4 primary gets more complicated.

But in general, if primaries are going to basically function as first-round election, then we ought to go whole hog on that. And open first-round election that whittles the field for the general election where RCV or some other method is used to ensure the winner gets a majority of votes.

The alternative is to force the parties to select their own candidates or, if they want to use the government-provided election system, make them pay the costs to run their private primary. As much as I like to be able to choose which primary I can vote in here in Colorado, that choice is bad. There should either be a single primary (first-round election) that everyone can vote in and all candidates are on the ballot, or candidate selection control needs to be returned to the parties.

The half-assed system we have now is terrible.

@Stormy Dragon:

If I were going to guess, my guess would be that the outcomes will depend on what types of people “throw their hat into the ring” multiplied or divided by the make up of the voting community’s attitudes. You’ll get different effects in highly urban and mixed generational Multnomah County than you will in mostly rural and predominantly ageing Cowlitz County.

@Stormy Dragon: As long as RCV works as it does in AK, you are highly dependent on the individual choices of the politicians who self-nominate. There is nothing about that process that would necessarily result in moderation.

And the rest is highly dependent on the partisan makeup of the district. Most arguments that RCV leads to moderation assume a bell curve of ideological distribution, which is simply not a good assumption to make.

The route to improving American democracy is modest PR, not RCV.

@Andy:

Honest to goodness, I don’t think that I am. I would really commend Jack Santucci’s work on this.

And other colleagues who study this stuff really do not think RCV will do what advocates assert.

This is especially true if party labels aren’t controlled in any way.

I am not going to say that under no circumstances would RCV produce a moderate candidate, but it will not systematically solve the problems we currently have.

Single-seat districts are the core problem, whether we fill those seats via plurality, two-round elections, or RCV.

Shift the conversation to multi-seat districts and RCV, I will change my tune (but I still prefer list-PR or MMP).

@Steven L. Taylor:

I don’t think RCV was ever intended to be a silver bullet. But you need something to address weak plurality primary winners, and a system that produces a majority winner is an improvement.

Single-seat districts aren’t going away anytime soon. Congress is not remotely interested in repealing the apportionment act, and so far, no states have sought to play with multi-seat districts. Achievable reforms need to take precedent.

And we would probably see this problem in a Presidential primary were it not for the strange way primaries work over a long period of time, with the early states having the most influence.

@Andy: The thing is, my position is not based on it not being a silver bullet. I am noting that it may be a BB at best, and I am not sure it is even that.

And, further, I wholly agree that single-seat districts aren’t going away any time soon, but I also think that hoping that RCV will do something that it is not likely to do will only prolong the time between now and real reform.

Perhaps it is better than nothing, but more likely than not it will be a lot of motion without much results. And it will have the effect of further weakening our parties, in a circumstance in which the weakness of parties is part of the problem.

I would note that Top Two inn CA was supposed to produce moderation, and it didn’t really change much in that regard.

@Steven L. Taylor:

Well, we don’t know until states experiment with this stuff. And I think it’s good that they are doing that. And there are other alternatives besides RCV that could be better.

Also, I do not think Top -2 is the same thing as RCV. You can have a top-2 system with a different voting mechanism.