Why Debating Defense Spending is So Hard

Nobody even agrees on what baselines to use.

Congress has authorized some $738 Billion in defense spending for the current year and wrangling is already underway for FY21 (and, indeed, FY22, FY23, and FY24). The Navy wants a bigger share of the pie, citing the National Security Strategy. The Army wants a bigger share of the pie, citing the disproportionate share of the load it’s been bearing in ongoing operations. The Marine Corps claims to be by far the most frugal. And that’s to say nothing of the Air Force and the new Space Force.

But AEI’s Mackenzie Eaglen points to a major problem: everyone is using different numbers to represent what they’re currently getting. And none of them are wrong.

Here’s an example. A common but flawed assumption persists that the total budget for the Department of Defense is divided roughly equally between the Army, Air Force, and Navy.

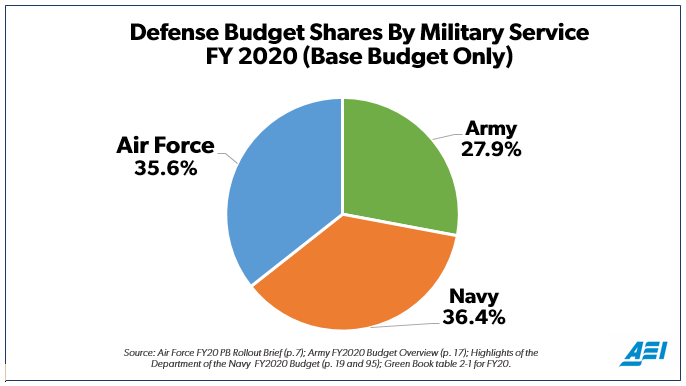

In the fiscal 2020 defense budget request, based on the pool of money allocated to the base budgets of the services alone, 35.6 percent goes to the Air Force, 27.9 percent goes to the Army, and 36.4 percent goes to the Navy (including the Marine Corps).

But those numbers are malleable. Whether a service chief uses only base budget numbers in making his case matters. Same with a service secretary including Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO) dollars in his or her arguments—especially now that a significant chunk of “emergency” funds are for entirely knowable and predictable base budget activities.

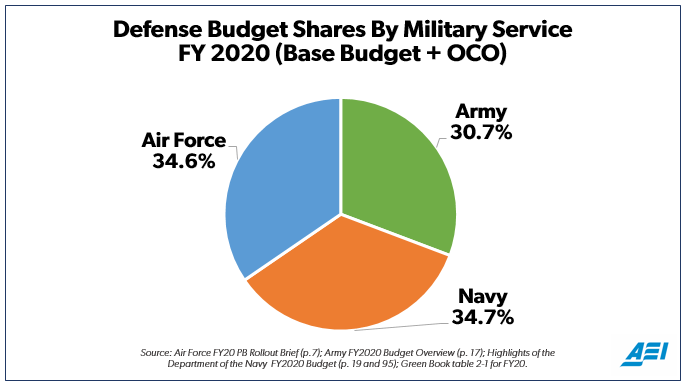

Therefore when you include OCO spending, 34.6 percent goes to the Air Force, 30.7 percent goes to the Army, and 34.7 percent goes to the Navy. Still, some of the services say this is an unfair analysis depending on their portion of global combatant commander requirements compared to their budget.

Whether overseas contingencies should be included in the base budget or remain a separate category is a topic that can be argued either way. Ditto whether it’s reasonable to include OCO in talking about how much a particular service is getting.

The Army, not unreasonably, says that it’s not. Its share of the budget goes up considerably when including OCO. And, yes, it’s spending that money. But, as the name implies, it’s spending it on operations, not investing in future capability. If the debate is about preparing for a future war with China and/or Russia—which the National Security Strategy is predicated on—then we shouldn’t count OCO.

The Navy, not unreasonably, says that we have to include OCO because, well, we’re spending money on overseas contingencies rather than investing in future capabilities. And the Navy needs to do the latter if it’s going to fulfill its mission. Oh, and for these purposes, the Navy includes the Marine Corps.

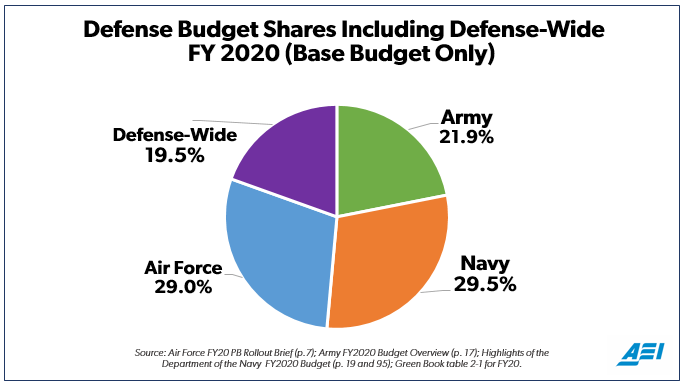

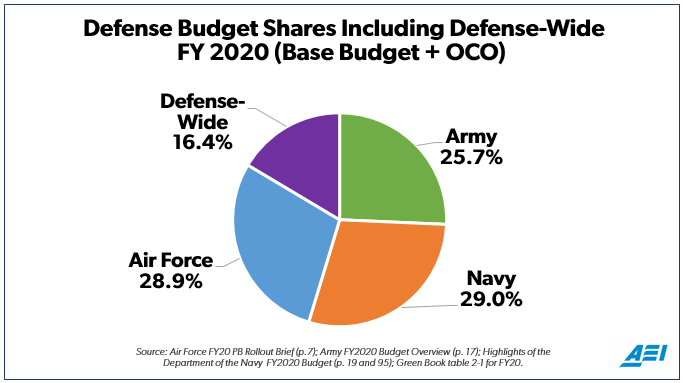

The two charts presented thus far obscure the overall debate, though, because the three departments (Army, Navy, and Air Force) and four/five services (the Marine Corps is part of the Navy Department and the Space Force is standing up under the Air Force) aren’t the whole budget.

But the military departments together do not comprise the entire defense budget. A huge portion of their spending exists outside departmental budgets for health care, allowing further obfuscation of what each military branch actually spends.

Still, comparing the uniformed service spending to an account fast-approaching the size of a standalone branch is helpful, namely defense-wide spending. From the Missile Defense Agency to Special Operations Command to Washington Headquarters Service, the so-called Pentagon “fourth estate” essentially refers to all of the entities within the Defense Department that are considered enterprise-wide. This ranges from administrative and support functions like human resources to combat enablers like the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) and DARPA.

Unlike the military services, the fourth estate resembles a loosely affiliated patchwork of semi-autonomous agencies. This spending accounted for nearly one-fifth of the defense budget in the 2020 request.

As House Armed Services Committee Ranking Member Mac Thornberry has noted, these agencies contain up to about a quarter of the Pentagon’s workforce — nearly half of its civilian personnel—and control a contractor army estimated at 600,000 people.

How does adding these costs in impact the numbers?

Eaglen goes through much more analysis, noting that there are many additional controversies. How does one count the large part of the intelligence community that’s nested under the Air Force? How about the Marine Corps?

Her conclusion is sensible:

All of the arguments are hotly contested—both within and between the services and do not account for every consideration that policymakers must weigh against the demands of the wider strategic environment facing the US military in the coming decade. Even so, it’s important to create a shared baseline. For analysis and potentially decision-making to shift these investments in the future based on a forthcoming joint warfighting concept.

Ultimately, each service can have their own set of numbers, but this does little to help make a decision. As the pressure mounts for senior Pentagon leaders to defend their respective priorities during the budget debates of fiscal year 2021, Congress must be presented with accurate information. Carve out everything or carve out nothing. Congress, and the Pentagon, should be working with the same set of facts.

But, as I’ve already noted, picking which set of numbers one uses slants the debate to the advantage of some services/enterprises and the disadvantage of others. Which numbers one uses really depends on what question you’re trying to answer. One size does not fit all.

Beyond that, “Who gets what share of the pie?” shouldn’t even be the question we’re trying to answer. Rather, we need to ask “What capabilities does the nation need the Defense Department to provide and in what capacity?” This, in turn, leads to more questions. Regardless, the debate shouldn’t be about a “fair share” of the pie.

Have long thought that the future development budget should be separate. My nephew’s partner does logistics for one of the three branches. It is incredible how much money is wasted.

Steve

Read through the post hoping you’d say something like that. Quite right.

Yes, this. The parochial service interests are probably too important.

If it were up to me, I think we are overdue for furthering what was started with Goldwater-Nichols. There is still a lot of duplication among the services and various agencies that don’t make much sense anymore.

Listening to NPR this morning about the growth in the naval budget to accommodate 355 ships (we are at about 306 currently). The Dept of Navy guy they were interviewing was basically incoherent. It basically went like this. Trump wants 355 ships. Navy creates the analysis to justify the 355 ships. There’s not enough money for 355 ships. So we have to buy smaller and less expensive ships to meet the arbitrary target of 355 ships. Its nuts.

What makes the DoD budgeting hard is that the wider defense establishment adds a lot of budget also. There’s the National Nuclear Security Administration budget ($14B) in Dept of Energy. The CIA ($30B), the VA ($220B). I’m pretty sure there are other defense related agencies also. A lot of interaction between the various departments.

We are well over a trillion for defense alone.

@Scott: And China protects four times as many people with $180 billion per year.

We have the money to make this a much better country, but we waste it on F-35’s that don’t fly and new tanks that go straight into storage.

Wait…wut?

It really isn’t that hard.

We spend way too fuqing much money on Defense.

See…easy.

@Scott:

It’s something that trump wants. What can it be other than nuts?

Ok. It might be bananas.

This is a case where it is actually worthwhile comparing to private industry. In a corporation, the different divisions would argue about the metrics and how to track but at the end of the day the Corporate C level would dictate a structure and set of metrics and everyone would work towards it. The only way to go over the head of the CEO/CFO is the Board, and that is a career ending move if you get caught. In private industry there is also less ability to creatively account since Divisional Finance almost always reports straight up to Corporate Finance, so it is hard to cook the books at the divisional level.

In the Military, the C Level is very weak and going straight to the “Board” (Congress) is the norm. And, if I understand correctly, the equivalent of Corporate Finance is also weak, and easily overwhelmed by whatever accounting tactics the Services employ.

@Scott:

Sadly, you can’t blame this bit of idiocy on Trump. The Navy wanted 355 ships, and knew they couldn’t afford to operate that many even if they could buy them for free, back when Trump was still firing apprentices.

Just the other day, the Navy admitted that they had painted themselves into a corner, and decided to scrap their long-term planning and start over.

@Teve:

Assuming we can trust China’s numbers, sure. But China is a developing country that pays its troops a small fraction that we must to attract and sustain talent in an advanced economy. Further, China is a regional power while we’re a global one.

@Daryl and his brother Darryl:

That’s an instinct, not a debate.

@Teve and @Daryl and his brother Darryl: How small should our Defense budget be? What should our aims be?Which alliance commitments should we abandon? What regions should we cede to Russian, Chinese, or Iranian hegemony?

@James Joyner:

No, it’s basic common sense.

Our Defense budget could be 30% less…no matter what baseline you use…and we still wouldn’t have to address any of those issues. We would only have to address bloat, both within the Pentagon, and in the Defense Industry itself.

Call that instinct, or whatever…but the fact is that the Defense budget has grown at a steady 5% every single year since the 50’s. That’s ridiculous.

@James Joyner:

In one sense I agree. If we debate our commitments and the force levels necessary to fulfill them then, yes. But if the question is whether we spend too much fulfilling those commitments, I don’t think there is any room for debate. Here’s just one example.

Back in the Reagan era when much of the country and all of the Republicans went all in on “the gummint cain’t do nuthin right”, a lot of vendors saw an opportunity. They convinced congress and the pentagon to outsource things like military food service, IT services and the like to private industry. I suspect in their vision it made sense because, hey, those services were going to bases in Marietta, GA or Japan or France. The locals just needed a base contractor pass. Even under those idealized circumstances did anyone check whether this was saving money? I sincerely doubt it.

Fast forward to the last 20 years of war. Not only do we have to pay private individuals hundreds of thousands a year as a cook to operate in an Iraqi base under constant threat, but we have to protect them with more soldiers. Long gone are the days when Charlie the cook was also the platoons best rifleman.

In almost any other government agency or in every private industry a mistake of this magnitude would get corrected. But because every congress critter has a civilian contractor in their district and every general knows they have a nice sinecure with one of them when they retire, the government just digs deeper into the next generations pocket to fund this terrible and dangerous system.

@Daryl and his brother Darryl:

Politicians and critics of government have been claiming that we can cut budgets without sacrificing anything real—just go after “fraud, waste, and abuse”—for at least the last four decades that I’ve been paying attention. I’m sure there is some bloat that could be trimmed in our ginormous Defense budget. But the vast majority of it goes to paying the salaries and benefits of people. Real savings requires a significantly smaller workforce (uniformed, civilian, contractor, whatever) and making hard choices on acquisitions. There are high-dollar programs I might be persuaded to cut were I king. But it’s extremely hard in practice because of how our budgeting process works.

@MarkedMan: I agree that the movement to replace uniformed personnel and civil servants with private contractors wound up being inefficient, likely costing more than it saved. But I don’t think we’re going to find massive savings there even if we had the political will to do it.

I was in a car wreck in 2018 and woke up in intensive care and in the next few months I’m going to be filing for bankruptcy and losing every asset except probably my car. it’s either that or 25% of my paychecks will be garnished for the rest of my life.

Why do I give a shit about us paying trillions of dollars to dominate the globe and we don’t have money for basic healthcare. But no, we have to dominate The Globe. We need another aircraft carrier, and some billion dollar planes that can’t fly when it’s sprinkling. Fuck that.

@James Joyner:

Yep. What really needs to happen is more fundamental reform of the federal government, which is still based on industrial-era processes developed in the 1940s.

Unfortunately, this is not a topic that any politician is interested in discussing – it’s simply much easier to argue over spending priorities than advocate for reforms that might actually make government more efficient and accountable.

@James Joyner:

This is what the conservatives say every time the subject comes up. It’s the same theory that causes people to decide that there’s no sense in saving because “I’ll never become a millionaire.” Is it possible that we should stop trying to find “massive” savings and just decide that saving is a virtue of itself? Should the government set the example?

(And yes, I know that government will not set the example because it’s easier to say “we’ll never find massive savings, so there’s no point in trying” and because grifting is what Congress does.)

@Just nutha ignint cracker:

Liberals say it too, just about different programs.

And it’s not like people haven’t examined this problem closely, including left-of-center defense think-tanks.

The problem is that it’s difficult to make the federal government be able to do the same thing with less money. Cutting the budget doesn’t magically create efficiency. You’ve got to change the system and there are always tradeoffs when doing that.

The Trump budget for 2020 that proposes these increases in military spending also includes a 9% cut in the budget of HHS. HHS includes the Center for Disease Control and Prevention. I hope that our 355 ship navy will have some antivirus capability.

@Teve: I’m sorry to hear about your health and financial woes. I’ve supported universal coverage going back to my College Republican days. Growing up in the Army, where everybody from private to colonel and their families got access to the same, mediocre care must have influenced me.

@Just nutha ignint cracker: No, conservative politicians routinely claim that there are massive savings in FW&A. There just ain’t.

@James Joyner:

I am happy that you favor universal healthcare, but only someone who has never had to deal with the real world of healthcare could think TRICARE is ‘mediocre’. If TRICARE were available to ordinary citizens, it would be a Cadillac plan. RAND estimated back in 2005 that a young military family would pay well over $3000 per year for a comparable private-sector plan, pay $500 more out of pocket per year, and have a much higher worst-case expense.

@DrDaveT: I’m old enough to have grown up in an era where TRICARE was a supplemental insurance plan vice the current default. In the 1970s and 1989s, Army healthcare was very much like the British NHS—you showed up at the clinic and waited your turn for the next doc. TRICARE was for the rare occasion you needed to get care off post, as when my mom got uterine cancer. We shifted at some point to TRICARE being primary insurance and retirees and dependents mostly relying on private care.