Drug War 101 (With an Emphasis on Coca Cultivation)

Here I am writing primarily about cocaine, although everything in this post can be applied to heroin as well. It should be understood that both are plant-based drugs. Cocaine’s most fundamental ingredient is the coca leaf, which grows almost exclusively in the Andean region of South America. Heroin comes from the opium poppy, which grows in multiple places. Most cultivation of opium poppy for US heroin comes from Colombia, although some is also to be found in Mexico. Marijuana is another major plant-based drug. It goes all over, including within the US.

The issue that I am primarily concerned with is the simple fact that we are wasting money on the drug war as it is currently constituted. Most people are reluctant to face up to this fact because they have fears about either drugs penetrating their own families, or just higher rates of addiction in the broader society. This tends to cause a reaction that is quite negative to any discussion of shifts in our anti-drug strategy. However, I have become convinced over the years that the drug war is an utter failure and a giant waste of money. On balance, the overwhelming majority of persons who actually study the process in an depth whatsoever tends to come to the same conclusions. Indeed, within the broader literature on this subject what one finds is that the only main proponents of the drug war are either people who work within the drug enforcement apparatus of the United States (which is vast network of agencies at this point in time) or are people who simply have very passionate views on intoxicants and see the war on drugs are a moral crusade. Yes, some exceptions can be found (James Q. Wilson comes to mind), but on balance to study the drug war is to realize what a waste it is. I say this having once been a general proponent of the policies.

A basic fact that has to be understood in terms of US anti-drug policy is that it is fundamentally a supply-side set of policies, i.e., we spend the lion’s share of our money on attack the source and distribution of the drugs. It is why, for example, we have spent as much money as we have in Colombia over the years and why we are spending it now in Mexico. Colombia has long been a major managerial nexus of the drug industry and after the US targeted (successfully, to some degree) cultivation in Bolivia and Peru, it became (and remains) a major source country. Mexico has recently become the main trafficking/management country, surpassing Colombian cartels. It should be noted that Mexico became the major transshipment route to the US for Andean cocaine and heroin after a decade+ struggle by the US government to curb trafficking through the Caribbean into Miami and the east coast in general. As the above paragraph notes, and will be illustrated further below, any given success (like curbing coca cultivation in Peru) usually leads to a shifting of the problem (to more cultivation in Colombia). It is what is called the Balloon Effect, i.e, squeeze one part of the balloon and it bulges out somewhere else. Along those lines, putting the squeeze on Miami has shifted trafficking into Mexico and so forth.

A supply-side policy means, as the name suggests, is one that targets the supply of the drugs. We have demand-side elements of the policy as well, which include locking up users. We also have some treatment and education based elements. The money, however, goes overwhelmingly to supply-side policies (especially military-based interdiction and law enforcement).

There are several basic metrics for success. One is the price of cocaine (noted in the previous post), while others include: the number of hectares under cultivation, the number of hectares eliminated, seizures, and arrests of traffickers. Let’s look at hectares under cultivation and to some extent hectares eliminated.

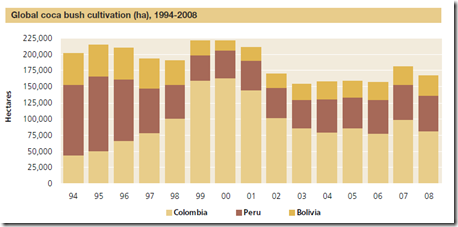

The chart to the right is from the 2009 World Drug Report [PDF] and shows thousands of hectares under cultivation from 1994-2008. Now, we see a couple of things here. First, the Balloon Effect is quite evident as starting in 1994 it is clear that the squeeze was put on Peru and on Bolivia around 1999. However, as those countries reduced cultivation, Colombian coca famers readily took up the slack. Indeed, with some variation (both up and down), coca cultivation in the aggregate remained pretty stable from 1994-2001. It should be noted that a lot of money was being spent on interdiction at that time and it was being hailed as a great success. After all, look how much coca cultivation diminished in Peru! However, how much of a success is a policy if it the net effect of all the effort and the spending is ultimately negligible? Indeed, the experience with Plan Colombia suggests that escalation of the drug war ultimately provides only partial results-perhaps even only negligible ones.

The chart to the right is from the 2009 World Drug Report [PDF] and shows thousands of hectares under cultivation from 1994-2008. Now, we see a couple of things here. First, the Balloon Effect is quite evident as starting in 1994 it is clear that the squeeze was put on Peru and on Bolivia around 1999. However, as those countries reduced cultivation, Colombian coca famers readily took up the slack. Indeed, with some variation (both up and down), coca cultivation in the aggregate remained pretty stable from 1994-2001. It should be noted that a lot of money was being spent on interdiction at that time and it was being hailed as a great success. After all, look how much coca cultivation diminished in Peru! However, how much of a success is a policy if it the net effect of all the effort and the spending is ultimately negligible? Indeed, the experience with Plan Colombia suggests that escalation of the drug war ultimately provides only partial results-perhaps even only negligible ones.

Now, it is true that cultivation was reduced, and specifically in Colombia, starting in 2002 as Plan Colombia, which despite its original billing was an interdiction/crop eradication heavy policy. It is fair to say that the policy had some effect. However, it is worth noting that while the policy helped take coca cultivation down from it peak, it did level out at a fairly high level (~150,000+ hectares). Note, also, production in Peru starts to creep up at the same time. Another point that needs to be pointed out is that if we look at net cultivation and the level and intensity of eradication in Colombia, we are left asking if we are getting good return on our dollars especially if, as was noted in the post on price, the eradication effort is not effecting supply enough to drive up price.

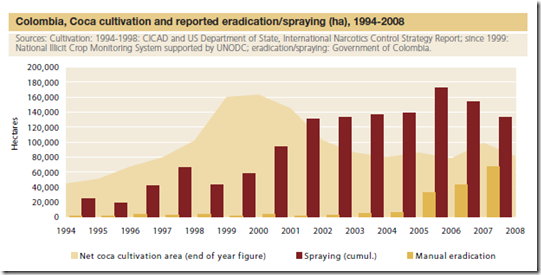

The Report provides the following on crop eradication and Colombia, and we can see that a great deal of eradication effort has been engaged in,  and yet the net cultivation has remained pretty steady. As such, a lot of money is being spent to destroy coca bushes, and yet the farmers have simply started planting more and more plants and have reached an equilibrium despite the actions of the US and Colombian governments. It should be noted that the coca bush is a hearty plant that is easy to grow and can be be harvested multiple times a year. And, because of the black market in coca leaves, it pays more to grow them than it does other traditional, and licit, crops.

and yet the net cultivation has remained pretty steady. As such, a lot of money is being spent to destroy coca bushes, and yet the farmers have simply started planting more and more plants and have reached an equilibrium despite the actions of the US and Colombian governments. It should be noted that the coca bush is a hearty plant that is easy to grow and can be be harvested multiple times a year. And, because of the black market in coca leaves, it pays more to grow them than it does other traditional, and licit, crops.

So, what we have here is a great deal of effort and money being spent so that the cocaine market can still sell drugs at a cheaper price than it did when all of this started. People die and billions of dollars exchange hands and it is still possible to get drugs in the United States if one really wants them. So I would ask, does this stand up to a basic cost/benefit analysis? Yes, I understand very well that drug addiction is bad and that it wrecks lives. However, that is happening right now in spite of the billions spent. Indeed, a lot of lives are being ruined because of the drug war. America’s cocaine habit (and to a lesser degree Europe’s) funds, for example, the FARC in Colombia and the drug violence in Mexico. Some people are more than willing to engage in all sorts of bad behaviors if they will make a lot of money in the process. The appetite for cocaine (and other drugs) in the US coupled with prohibition equals a lot of money to be made. It means, therefore, a lot of violence to protect that money. Indeed, a lot of the violence in the southwestern United States that is being attributed to illegal immigration is really a lot more about the drug war and drug trafficking than it is about illegal immigration as we typically use the term.

The question becomes: are we getting what we, as a public, think we are getting from the drug war? Is it worth the cost or should we have a serious public debate about another way of doing business?

The question becomes: are we getting what we, as a public, think we are getting from the drug war? Is it worth the cost or should we have a serious public debate about another way of doing business?

This could become an interesting series of posts on this blog but you’re asking questions of readers and not really providing any basis upon which they can answer with any substance.

What we did a number of times on my blog was write the best counterfactuals we could so as to make the strongest case of our critics and then we addressed the issues that we, and our critics, spelled out. Why not do the same here, use your expertise and write the best-case counterfactual in support of the Drug War and list all the benefits that arise, especially the ones that can be documented. Then follow-up with your favored position and write about what you actually think are the costs to society from perpetuating a Drug War. Then a post on how we should go about valuing the costs against the benefits, should it just be a decision based on fiscal costs, or what?. Wrap up with a post about how you think that the landscape would look like after a cessation of Drug War policies.

What I see you doing now is making your case but you’re doing it in kind of a vacuum because no one, with your level of knowledge, is presenting the opposing view. In this sense, a one-sided argument is going to have limited persuasive utility.

I’m engaging with you on piddling issues like study design and semantics, but that doesn’t really advance the state of debate and I don’t see others who frequent this blog stepping forth and forcefully arguing in favor of the Drug War. The upshot is that everyone is kind of, more or less, just nodding their heads because you’re either writing a piece which confirms their bias or because what you write makes sense so long as it isn’t challenged by a counter-argument.

Your comment is just weird, Tangoman. Indeed, I don’t think it’s even a valid criticism.

The “opposing view” in this case is an actual policy. It’s enshrined in the legal code, and the Office of National Drug Control Policy presents it all the time. For FY 2011, they have a budget of $401.4 million bucks, a number I got from this document. Over the last ten years, taxpayers have spent almost $10 billion to fund the ONDCP.

$10 billion to present the “opposing view!”

Besides I recommend you take your own advice. Before commenting on a subject, first offer a full and fair accounting of the opposing view. If you don’t, you’re just arguing in a vacuum…

Your comment is just weird, Tangoman. Indeed, I don’t think it’s even a valid criticism.

If you’ve never tried to argue a counter-factual case before then I can see how you might think it weird. I doubt that anyone who’s been through a doctoral program will join you in your opinion though.

Secondly, it’s not a criticism at all. It’s a comment. Unless a co-blogger, or a commenter, steps forth and argues for the merits of the Drug War and is specific in support of his position as Steven is with his detailed posts, then all we’re getting is Steven arguing a point with most people agreeing with him. My personal bias leans towards a policy reform on this issue but until I see a pro v. con debate, I don’t know enough to make an informed decision because I don’t really think too much about the Drug War and I just operate with a surface knowledge. It’s pretty orthogonal to my existence.

Look at the closing questions Steven is asking. If he’s preaching to the converted then he can basically save his effort because his posts, while informing us, aren’t convincing people to, as he writes, “have a serious public debate about another way of doing business?”

The “opposing view” in this case is an actual policy.

Yeah, no kidding. Thanks for that news flash. My point is that no one is really stepping forward and arguing strenuously in favor of the Drug War against the position that Steven is laying out in his posts.

Before commenting on a subject, first offer a full and fair accounting of the opposing view. If you don’t, you’re just arguing in a vacuum…

Dude, I serve the function of foil in quite a few threads. Perhaps I’m experiencing selective amnesia in regards to the vigorous debate in these past threads – refresh my memory, who’s stepped forward in comments and presented a strong case in favor of the Drug War?

Where is this counter-factual you speak of? I see charts and facts but no counter-factuals.

(And what would you know about doctoral programs anyway?)

Um…that usually happens with good arguments. They’re persuasive.

But, as I’ve demonstrated, that’s not true. There’s a well-funded government agency “arguing strenuously in favor of the Drug War” all the time.

Oh, you meant on OTB? Why should Steven L. Taylor or any of OTB’s commenters duplicate the ONDCP’s efforts? Tell you what…you want to give me a $400 million budget, I’ll put together a pro-drug war case for ya. I’ll even post it right here for all to see.

@TangoMan:

My basic response would be that I don’t think that I am preaching to choir, even though it is clear that there are people out there who agree with me.

First, as many noted above, the prevailing view in terms of both government policy and public opinion is in opposition to mine. It isn’t like I am blogging about how puppies are keen or that literacy is a good idea. There is a great deal of opposition to my position.

Second, I look at a post like this to be educational in nature. Most people don’t know anything about this stuff. They basically say to themselves “Drugs are bad, and so a war on drugs must be good.” However, most people don’t think much about it beyond that.

First cultivation went from approximate average of 200,000 from 94 to 01 down to around 150,000 from 01 to 08 which about an 25% decrease. Not too shabby.

Second the argument that “total†supplies must be higher since the price is lower doesn’t even hold true in an economic 101 class. Yes price due to supply vs. demand is in a basic model in economic 101 but even those classes usually teach that many other factors can lower the price.

However even using basic economic models, price due to supply vs. demand is relative to each other not the total of just one. If supply goes down but demands goes down even further then price goes down. Many consider cocaine as yesterday drug and are moving to things like meth. Cocaine can also be cheaper because of more fierce competition between entities. Then there is ability to cut price due to cutting overhead considerations.

What does that all mean n the end. It means that you can’t “justifiably†state that because the price is lower that the “total†supply is higher.

Yes, but was it worth the expenditure? And it does not appear to have substantially affected the supply of cocaine.

I never said that supply was the only effect on price. Indeed, part of the overall point is that prohibition itself is driving up price artificially.

However, you are ignoring the more fundamental point: a major component of US interdiction policy is to control supply and one of the goals of that control of supply is to drive up price. Yet, it hasn’t even come close to accomplishing that goal.

This is a rather important issue when trying to evaluate the policy.

And BTW, if that’s true, then how much more stupid are our policies?

The end goal is to end its use. There are many methods to do this including methods to decrease the demand and methods to decrease the supply. Finding a way to increase the price is one way but not they only one. Also keep in mind that keeping the price higher than it otherwise would have been still helps your cause. The only problem with judging such a tactic is it is very hard to determine how “worst off†something could have been.

Re†Yes, but was it worth the expenditure? And it does not appear to have substantially affected the supply of cocaine.â€

It has on those three countries you listed. Where is your support for that statement? Unless you are still claiming that lower prices is proof that “total†cocaine supplies are higher as they have ever been.

IMO the policies are worth the expenditures.

Yes we are fighting the war on drugs on many fronts. Which mean we go after cocaine, meth and anything else that is out there. To not do so would be foolish. If we went strictly after meth then other drugs like cocaine would be more popular.

Yes, but was it worth the expenditure? And it does not appear to have substantially affected the supply of cocaine.

OK, I’ll play. Yes, it was worth the expenditure. Case closed now?

I’d say that a 25% reduction in supply is substantial. It seems that you’re establishing unrealistic benchmarks by which to judge success.

However, you are ignoring the more fundamental point: a major component of US interdiction policy is to control supply and one of the goals of that control of supply is to drive up price. Yet, it hasn’t even come close to accomplishing that goal.

If the Drug War takes consumers out of the market, for whatever reason, then that seems to me to be a successful byproduct of the initiative and it is equally, if not more, important than reducing price, in that it has the same effect on market demand that high price would.

It appears that you’re selectively choosing your metrics and you’re not weighing competing metrics adequately.

Why would you deem the initiative a success if it forced cocaine prices up to $1,000 a gram thereby lowering demand for the product to 10% of the number of users from a benchmark year, say 1990, but minimize the same deterrent effect created by fear of incarceration even in a market environment where cocaine is priced at $100/gram and then deem the Drug War to be a failure?

Two things:

1) A reduction in hectares under cultivation is not the same thing, ultimately, as affecting the supply on the street, which has not seen an substantial, sustained reduction.

2) Not unrealistic at all. The issue is not the number, but whether the overall goal is met. If one allows an 11 yard run 25% of the time and 0 yards 75% of the time in football, you will lose and lose grandly.

We are spending billions of dollars, helping to destabilize countries and ultimately not stopping the drugs from making it to the US, even with crop reductions. The issue is not how many bushes you kill, it is how much cocaine ultimately makes it to market.

Crop eradication does not take consumers out of the market. Further, the goal of the policy is to take consumers out by driving up price–which isn’t happening. That’s the whole point–the policy isn’t working as it is designed to work.

The metrics I am discussing, wholesale price and cultivation/eradication are the chosen metrics of the drug warriors, which is why I used them. My point is that based on the metrics used by the US government, they policy is failing.

I am not entirely sure what you are trying to say in the last paragraph. However, I would refer you again to the fact the price metric is something the US government targets and further I would note that despite threats of incarceration, lots of people still do cocaine. Indeed, that again makes my point: the policy doesn’t work as stated.

I suppose it is for you, which is your right, of course.

However, I think it is odd to assert that the policy is worth the money since by its own metrics it doesn’t work, unless the goal is question is simply to destroy coca bushes. We have been pretty good at that.

And it’s a fool’s errand. People have been using intoxicants for 100s of years, and have continued to do so even with a 4 decade “war on drugs”.

You are confusing coca cultivation with cocaine supply. It is not the same thing.

I will, no doubt, return to that issue.

TangoMan:If the Drug War takes consumers out of the market, for whatever reason . . .

Steven L. Taylor: Crop eradication does not take consumers out of the market.

Drug War /= Crop eradication.

Further, the goal of the policy is to take consumers out by driving up price–which isn’t happening.

This doesn’t make sense. Goals are usually measured by outcomes, not by means. The goal here is to reduce cocaine consumption. One of the means of doing that is to increase price. However, to declare the initiative a failure if cocaine consumption goes down while the price of cocaine hasn’t risen is nonsensical.

Steven L. Taylor: Yes, but was it worth the expenditure?

TangoMan: OK, I’ll play. Yes, it was worth the expenditure. Case closed now?

My point in this exchange was to answer what looked like a rhetorical question on your part. You’re asking us to make a cost/benefit judgment and you haven’t laid out a case for us to consider. You’ve presented a surface argument by quoting street price of cocaine, crops under cultivation but you haven’t yet explored the benefits that arise in America from efforts to control drugs. It’s clear that you think the expenditures aren’t worth it but I’m not exactly sure why you’ve reached that decision. I get that your area of expertise is Colombia and Latin America and you’re likely factoring in the costs of the Drug War that fall on those countries, but to me, those costs are immaterial, that’s just realpolitik, and they’ll remain immaterial until a convincing argument is put forth why those costs should matter to me.

And it’s a fool’s errand. People have been using intoxicants for 100s of years, and have continued to do so even with a 4 decade “war on drugs”.

I don’t think many are disputing the historical use of intoxicants. You know what else has been prevalent throughout history? Older men sleeping with young teen girls. In fact, older men used to actually take as wives, girls who were as young as 14. In fact, there are alive today in the US, old women who lived this experience. It’s a fool’s errand to deny the allure of youth or to try to control the behavior of adult men on this matter, right?

I am not entirely sure what you are trying to say in the last paragraph.

Let me take another stab at it. The way I’m reading your argument the only way you see of gauging success is to measure one metric – price per gram, because it is understood that higher prices will drive users away from the product, thereby reducing consumption. What I’m saying is that if consumption falls independent of the price mechanism, that should be judged a success but you seem to be categorizing that as a failure because you’re focusing solely on the price not rising.

Yes, but what we are talking about here is crop eradication and you made the claim in that context.

No, not rhetorical at all. My whole point is that we, as a public, do not give this question enough consideration. We simply say: “Drugs are bad, so war against them must be good” and then assume that if we didn’t have the war on drug things would be worse. We don’t actually ask the questions that need to be asked. I believe that if a policy is failing it should be canceled or revised.

Let me try again: I am trying to talk about this one variable at a time. We are dealing here with blog posts, not a book. I am trying to go one at a time. First with price, then with cultivation and more to come.

The point you seems to keep avoiding is that the US government is trying to make the price go up. And it isn’t working.

That is not the totality of the drug war, and I am not arguing that it is.

Where is your evidence of falling consumption of a level that would justify the expenditure? You are assuming facts not in evidence.

Of course, disrupting Columbian distribution networks have been much more effective than eradication. Unfortunately, this led to the Mexican cartels taking primary control over funneling drugs into the US and has created the current situation across the border.

Thus, the only real “success” of the drug war has shifted the violence and instability North from Columbia to our southern neighbor. Hurray!

My whole point is that we, as a public, do not give this question enough consideration. We simply say: “Drugs are bad, so war against them must be good” and then assume that if we didn’t have the war on drug things would be worse. We don’t actually ask the questions that need to be asked. I believe that if a policy is failing it should be canceled or revised.

I think that your simplistic phrasing is a pretty accurate description of the dynamic at work but you know, it applies to a host of issues.

Corruption is bad, so war against corruption must be good and then assume that if we didn’t have the war on corruption things would be worse.

Child porn is bad, so war against child porn must be good and then assume that if we didn’t have the war on child porn things would be worse.

Cheating on tests is bad, so war against cheating on tests must be good and then assume that if we didn’t have the war on cheating on tests things would be worse.

Reckless driving is bad, so war against reckless driving must be good and then assume that if we didn’t have the war on reckless driving things would be worse.

Even though these points of view are simplistic, they seem to be widely held and have levels of support. I’m not sure this simplistic framing of the Drug issue is a sufficient indictment on the invalidity of the framing.

We don’t actually ask the questions that need to be asked.

I’m looking forward to the post in which you lay out the questions that you think should be asked.

Let me try again: I am trying to talk about this one variable at a time. We are dealing here with blog posts, not a book. I am trying to go one at a time. First with price, then with cultivation and more to come.

My apologies. I await future posts to get a fuller picture of your argument.

The point you seems to keep avoiding is that the US government is trying to make the price go up. And it isn’t working.

I’m not avoiding that at all. In a comment in the post previous to this one I addressed this issue with respect to the differences we see in contemporaneous international metrics versus longitudinal metrics. It isn’t working if we judge by longitudinal metrics but it certainly is working by contemporaneous international metrics.

I feel that this distinction is relevant, you clearly favor a longitudinal metric. The fact that there is disagreement on the significance of the metrics doesn’t mean that I’m ignoring your points.

I believe that if a policy is failing it should be canceled or revised.

I look forward to your posts on the effects of policy changes. I guess this plays a part in why I thought you were asking a rhetorical question. I find it difficult to consider the question until I have a better understanding of alternatives, so the question seemed premature and of a rhetorical nature.

Of course, we don’t spend billions on the things you list, nor do we disrupt whole countries in pursuing our policies. You act as if you do not understand the scope of the drug war, and perhaps you don’t/perhaps I am assuming too much based on your interest in engaging the topic.

I will post more as time and energy permits and I invite you to weigh in as you see fit.

In all honesty, I am not sure what your overall point is, but time will tell, no doubt.

” I am not sure what your overall point is”

Tango appears to be asking for more metrics than just cost of cocaine. If you are doing a series, then you could look at the number of civilians killed in the Drug War (Balko is a good source). You could add in the cost of prison and prosecutions. Then, show the incidence of drug use in the US and how it has changed or not changed during this same time period. Maybe compare it with countries where there is lax enforcement.

For the people who see this as a moral cause, “drugs are evil”, almost no cost will be too high. Killing thousands of innocents so that we can jail thousands of pot users? That will be ok with them. Just collateral damage. Spending $50 billion a year but nothing is changing? They will assume it would be worse if you dont spend that, and TBH, you cannot prove otherwise.

Steve

Of course, we don’t spend billions on the things you list, nor do we disrupt whole countries in pursuing our policies.

Is that the crux of your objection – scale of spending? If we spent the same amount on the War on Corruption as we spend on the War on Drugs would you be advocating that we should live with reduced spending on the War on Corruption and be prepared to pay bribes as a way of life?

You act as if you do not understand the scope of the drug war,

I’ve already stated that I don’t command much knowledge on this issue as it’s pretty orthogonal to my life. I’m not advancing a counter argument to what you’re presenting, I’m simply testing the validity of what you’re presenting. I’m open to being convinced by your point of view but these few posts haven’t been sufficient to sway me yet. You want to convince your readers that the Drug War hasn’t decreased the street price of cocaine and you cite historical trends but I pointed out that, citing your data source, the street price in the US is one of the highest in the world. I think that observation merits some consideration in reference to the claim that the Drug War hasn’t decreased the price of cocaine. What I did here was test your claim and I didn’t find it as convincing as you think it to be. It appears to me that the Drug War is raising the street price of cocaine above its natural equilibrium based on what it is selling for in a variety of international markets. The Drug War is raising the price of cocaine but it is falling as part of a time-series trend. That’s a complex finding. I think it should be duly considered when evaluating the efficacy of the Drug War effort.

I see the shortfalls of current policy but I’m pretty pessimistic guy when it comes to governing structures and human nature, so I need to be convinced that there is actually a better alternative because I can make peace with living with the best option from a selection of really bad options. Right now I’m tentatively holding to the position that the Drug War is the least bad option. Maybe further arguments from you can convince me otherwise and then I’ll change my tune.

Tango appears to be asking for more metrics than just cost of cocaine. If you are doing a series, then you could look at the number of civilians killed in the Drug War (Balko is a good source). You could add in the cost of prison and prosecutions. Then, show the incidence of drug use in the US and how it has changed or not changed during this same time period. Maybe compare it with countries where there is lax enforcement.

This. Also, I’d like to see the benefit side explored.

I’m a critic of a number of liberal policy initiatives and I have no issue with detailing the benefits that derive from some of these initiatives, in other words, I can make a case for the liberal side of the argument. It’s just that I can make a far stronger case against than I can for, and so the balance of strengths/weaknesses or costs/benefits work to favor my position.

I imagine that even critics of the Drug War concede that there are some benefits. I really want to see what happens to those benefits if we cease prosecuting the Drug War.

Re “Of course, we don’t spend billions on the things you list, nor do we disrupt whole countries in pursuing our policiesâ€

Actually we spend more on those things Tango listed than we do on war of drugs.

The point remains that even if attempts to stop some bad behaviors results in only the reduction of said behavior, does not means that the attempts are pointless or a total failure.

Like murder or stealing, we will never stop 100% of the currently illegal drugs use. That doesn’t mean we are not successful in reducing it.

Re†You are confusing coca cultivation with cocaine supply. It is not the same thing.â€

Actually it sounds like you are. Now less coca cultivation does mean less supply to the next intermediaries. However what we are mainly concern with is the end users. If interdiction is lesson then supplies for the end user can increase even with less coca cultivation. However the chances of decreasing the supply to the end users are much greater if you decrease the supply to each intermediary link. Decrease cultivation and increasing interdiction at every stage will decrease supply to the end user.

Does this mean price will go up? No. If demand is decreasing as fast or faster or if there competitor price war then price would still go lower. You claim supplies are greater but only back it up with only “we know this because cocaine is cheaperâ€. Someone already state that even that is not true at all stages.

Once again the goal is to decrease consumption. Rising prices is only an intermediate goal. To say the policy is a failure if it reaches its ultimate goal without reaching some of the intermediate goal is foolish. Since you like football, it is like saying you lose if intermediate goals were to hold number 43 to less to a hundred yards and to run as much you passed but you didn’t achieve them. Never mind that you score 35 to your opponent 7. You a failure you didn’t meet your intermediate goals.

As for your football analogy, in many cases not true. For example, assuming all else is constant if you allow three consecutive 11 yard run\pass and allow the next 9 time 0 yards, the other team won’t score.

To restate Tango, yes we know that you think the war on drugs is pointless. Besides giving us your opinion (IYO), you haven’t given anything sound to back that argument up. Reduction of production by 25% doesn’t support it. IYO the reduction isn’t worth the cost but that is IYO. The price of cocaine isn’t as high as you would like it to be. That doesn’t make the war on drugs pointless either.

One more thing Steve, it is one thing to say that the war on drugs haven’t increase the price of cocaine over the last 20 years and another to say that the the war on drugs haven’t increase the price of cocaine therefore the war on drugs is pointless.