Jail Where Judith Miller Is Held: Maximum, Modern Security

The New York Times has an interesting discussion of the jail its reporter Judith Miller is expected to call home for the next four months.

Jail Where Reporter Is Held: Maximum, Modern Security (NYT, July 8)

There are no bars in the 70-square-foot cell that Judith Miller, the New York Times reporter, is expected to call home for the next four months or so, as she serves her contempt-of-court sentence in the Alexandria Detention Center in Virginia. But though the jail has a reputation among lawyers and corrections officials as a relatively progressive institution, Ms. Miller indicated to her lawyers yesterday that the detention center seemed overcrowded and that she was told she would be sleeping on the floor last night because of a shortage of beds.

Ms. Miller was sentenced to jail in the Washington area on Wednesday for refusing to cooperate with a special prosecutor’s investigation into the disclosure of the identity of a covert C.I.A. operative, and entered the detention center later that afternoon. The staff was “extremely professional and very courteous,” she said from jail Wednesday night. After spending about a day in the initial receiving area, she was moved into the general population yesterday.

The Alexandria Detention Center, opened in 1987 at a cost of $15 million, adheres to a corrections philosophy that tries to use architectural and management styles different from the norm to reduce the tension between inmates and staff members. In contrast, the District of Columbia jail has been plagued by safety problems and overcrowding.

“When they tell you it’s a ‘new-generation jail,’ that’s not just a bunch of hype,” Melinda Douglas, the public defender for the City of Alexandria, said of the Alexandria jail. “They just don’t throw you in a cell and expect you to manage,” Ms. Douglas said.

Though the jail is considered maximum security, the layout of the eight-story building is reminiscent of a dormitory, with cells lining the outside walls and a lounge in the middle. The 450 inmates live in cells with doors and windows rather than bars, and are spread through housing units holding up to 90 people each where they are supervised by one or more deputies, said David Rocco, a captain in the Alexandria sheriff’s office.

In the lounges, inmates can watch television, play cards or otherwise be outside their cells except for shift changes and head counts during the day and for eight hours at night. Inmates may make unlimited collect calls and have radios and CD players in their cells, and have access to programs taught by volunteers. “You respect them, and in return they respect you,” Captain Rocco said. But, as Ms. Douglas noted, it’s still a jail and “it’s still no fun.” Ms. Miller has to wear a green or brown jumpsuit with the word “prisoner” on the back. She can receive visitors only on weeknights except Friday and during the days on weekends.

Among her fellow inmates is Zacarias Moussaoui, who recently pleaded guilty in connection with the Sept. 11 attacks. The local jail takes federal inmates through a contract with the United States Marshals Service.

While it’s really sweet that they make life so pleasant for the inmates, it still sounds like too much security for a middle aged reporter with no history of violence. Miller is the classic case of someone for whom the expense of maintenance in a corrections facility makes no sense. Why not simply sentence her to home confinement without access to a computer or the ability to give interviews for four months?

They should do that with a LOT of “criminals”

Because sometimes prison isn’t just about incarceration or preventing a repeat offense, it’s about punishment. And punishment needs to be unpleasant.

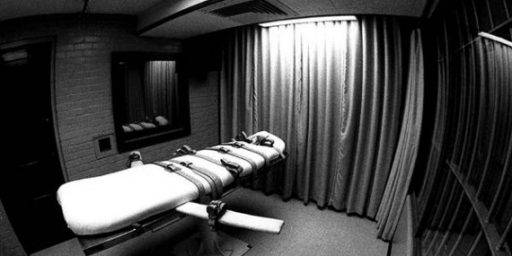

I was also very interested in this story, including the accompanying picture.

Cutting her off from interviews might well be viewed by an appellate court — and would certainly be challenged by her employers and their superb common lawyers — as an abuse of Judge Hogan’s discretion. For a reporter in her position, that would be a far worse punishment than incarceration in the very comfortable accommodations she’s now in. And cutting off her access to the press (as opposed to her ability to continue her gainful employment) might actually raise much more serious First Amendment issues than her attempts to quash the grand jury subpoena she’s defying.

I agree that she’s no security risk — neither posing a risk of escaping nor a risk of harming herself or others. But that’s not the main point of her incarceration, and any type of “home confinement” would be a mockery. It’s effectively the same as grounding an unruly teenager. The purpose of jailing someone for civil contempt is not punishment, but coercion (within the bounds of the law). That includes, for example, her being taken to the jail in manacles and wearing the jumpsuit. And I presume Judge Hogan either directed or approved her incarceration in this particular facility (as opposed to others that might be less pleasant and more coercive) as a measured exercise of his discretion. If she continues her defiance past the expiration of this grand jury’s term, is predictably re-subpoenaed, continues her defiance, and is re-sentenced again for civil contempt, Judge Hogan’s discretion would also extend to having her moved to a less comfy (but still constitutionally adequate) facility. He’s got a lot more flexibility about that sort of matter than in limiting her press contacts.

I value the public demonstration of the need to comply with valid court orders as well worth the cost to the taxpayers of her incarceration. In her particular circumstances, those costs are going to be more than offset in all probability by the fines she (or the NYT, voluntarily, on her behalf) will ultimately have to pay.

A point of further clarification: If she were found guilty of criminal contempt of court (or related offenses like obstruction of justice), then punishment would indeed become appropriate.

Since she’s only been found guilty of civil contempt, however, she “has the keys to her jail cell in her own hands.” Once she agrees to comply with Judge Hogan’s order and pays any accrued fines, she will have “purged” herself of the contempt, no further coercion will be needed, and she’ll be free.