The States and the Framers (Again)

Madison argued that the people were the ultimate authority.

It is often alleged in conversations about federalism (and especially ones that revolve around the 17th Amendment) that state’s have unique qualities that lend themselves to being represented in a way that is somehow different from representing the people in said states. Further, the argument is sometimes proffered that this is what the Framers intended.

It is often alleged in conversations about federalism (and especially ones that revolve around the 17th Amendment) that state’s have unique qualities that lend themselves to being represented in a way that is somehow different from representing the people in said states. Further, the argument is sometimes proffered that this is what the Framers intended.

The position is typically that the House represents the people and the Senate represents the states. However, I would counter that since the states are ultimately made of people, that one cannot stop the analysis with the notion that the states are someone separate from the people who live within them.

Assertions about state sovereignty apart from the populations of said states miss a couple of rather key points.

1) We had a government wherein all the states were truly sovereign, co-equal entities as this was what we had under the Articles of Confederation. It failed.

2) The entire purpose of the Philadelphia convention was to subordinate the states to the central government. This is a fact that utterly impossible to deny or refute. Yes, one can argue over the extent of said subordination, but one has to first acknowledge that subordination was the goal. Again: s system of co-equal, sovereign states had been tried and it did not work.

3) As I noted in a recent post, James Madison went to Philadelphia hoping to severely undercut the power of the states—although he did not achieve all of those goals.

4) The reason we emerged from Philadelphia with federalism (a system with both a strong central government but also with strong states) is because it was necessary to find a political compromise that would allow the states to give up a great deal of power while still not giving up all of it. Federalism was born of political compromise, not grand design and certainly not from an imperative to treat the states like sovereign entities in the way meant by revisionist interpretations of the 17th Amendment . On that latter point we have to return to item #1 of this list: we had such a system and its failure led to its rejection.

Now, recognizing the caveats I noted in the above linked post about quoting the Framers/Founders, let me quote James Madison from Federalist 46 on the question of whether the states are to be considered units apart from the people who populate them:

The federal and State governments are in fact but different agents and trustees of the people, constituted with different powers, and designed for different purposes.

Note we have here Madison’s basic approach to what he called republican government: the delegation by the people via the vote to the government to act as agents of said people. Further, the notion of accountability via regular election is central to that model (see, for example, Federalist 39 on this topic). Madison assumed that the agents of the people would serve for set amounts of time at the pleasure of the people (i.e., that at regular intervals they would have to seek re-election).

More important to the topic of the post it should be noted that Madison does not here consider the states to be unique entities in and of themselves. In other words, he does not delineate a theory of the constitution as representing the states on the one hand and the people on the other.* Rather, he sees them as being agents of the people just like the central government, just with different responsibilities (i.e., federalism).

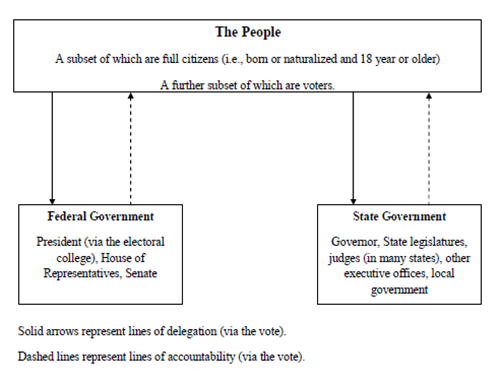

The basic relationship can be detailed as follows:

Such a model does not envision states are having their own interests apart from the people living in them.

Interestingly, Madison went on from the quote above to state

The adversaries of the Constitution seem to have lost sight of the people altogether in their reasonings on this subject; and to have viewed these different establishments, not only as mutual rivals and enemies, but as uncontrolled by any common superior in their efforts to usurp the authorities of each other. These gentlemen must here be reminded of their error. They must be told that the ultimate authority, wherever the derivative may be found, resides in the people alone…

Interestingly, the opponents of the 17th Amendment make the same error that the anti-Federalists did: they look to the states as the ultimate authority in some cases, instead of looking to the people.**

None of this is to say that the states were considered unimportant (indeed, quite the contrary). However, the issue is whether the states can be construed as having their own, unique interests as states. They do not because the only thing that animates them as political entities in the first place are the people who reside within them.

—-

*Indeed, it is worth nothing that the preamble of the Constitution states “We the people of the United States…” and not “the states of the United States.” Indeed, one can contrast the preamble of the Articles with that of the Constitution and see two different approached to constituting the union. In the Articles case the document is drawn up as a charter of sovereign states while the Constitution is a charter agreed upon by “the people.”

**Indeed, it is remarkable the degree to which many alleged defenders of the US Constitution in the current era sound like anti-Federalists. While they are certainly free to hold said views, it should be understood (lest it is not obvious) that the anti-Federalists opposed the ratification of the Constitution.

I agree overall. But I suppose a counterpoint would be to say that a bicameral legislature is in and of itself proof of a competing power. Otherwise, you’d be making the argument that the creation of the Senate was intended to make some people more equal than others. To me it’s simply easier to go with the State vs. people view of things. Plus the tenth amendment also reads better when treating the states and people as separate things.

We also have to look at how the “founders” defined “the people”. My readings would indicate it was not like we define it now. In fact it may have been closer to what Matthew Vadum is saying. I disagree with this but I can’t deny that may have been what the founders were saying.

@Ron Beasley: The issue of defining “the people” is a fair one, and worthy of elaboration at some point. There is little doubt that the original conception was far more limited than the contemporary conception of the term.

I often hear politicians talk of the 10th Amendment and the need to adhere more closely to it, but I rarely hear the 9th Amendment mentioned at all, especially vis-a-vis issues of liberties. Is this a symptom of the same mentality?

@pajarosucio:

I can see why people would differentiate the ninth and tenth amendments. The constitution works the same with or without the tenth amendment. Really, the tenth amendment is code for “I may not know what the constitution actually says, but surely the government can’t do that thing I don’t like them doing.” Without the tenth amendment, Congress still can’t assume powers that aren’t in the constitution.

However, without the ninth amendment, it’s perfectly reasonable to come up with a hypothetical situation where the government uses powers it already has to squash a right that isn’t in the bill of rights.

The reason conservatives get ass backwards on the amendments they support is because despite the rhetoric, conservatives are authoritarian instead of liberal/libertarian. There aren’t too many conservative pet causes where invoking the 10th amendment will lead to some radical increase in freedom. Federalism, schmederalism

@Console:

Boy, do you have that backwards!

The 10th amendment is what the SCOTUS used to beat back some of FDR’s overreaching legislation in the 30’s, by declaring certain acts simply unconstitutional. This amendment was designed to limit government’s scope over the people, which is why social progressives find it so obstructive to their broad and utopian-like agendas.

The 9th amendment was brilliantly considered, as the Founding Fathers realized they couldn’t possibly list every natural right of human beings that needed protection. Consequently, they delegated certain powers to the government that were specifically spelled out in the Constitution, and said everything else is left up to individuals and to their state governments.

The wording in the 9th is so relevant and important, as intellectuals tend to quibble and parse wording in order to change the intent to the way they want it. The 9th amendment, though, is cut and dry in asserting that what is Constitutionally stated is what is within the government’s perimeters or jurisdiction . And, what is not stated is not, and is given to the people to decide, clearly containing government powers that would otherwise tend to grow, oftentimes in a malignant, oppressive fashion.

I used to think that a liberal was just that, liberal-minded. However, as time has gone on I find that being liberal is a paradoxical term when used in politics. For, most of the policies of liberals are far from liberating. They confine freedoms, try to do away with market competition (especially involving unions), are very anti-individual prosperity, opting for wealth redistribution through various forms of high progressive taxation, and dislike free choice (except in abortion) when it comes to education, the work place etc.

These are not mutually exclusive. It required a pretty grand design to square the hole between states as entities* and people as entities. That the architect of the design might have preferred something different if left to his own devices doesn’t change the fact that the design he produced gave us one house treating the (voting) people as equals (more-or-less) and the other treating the states as equals regardless of the number of people within them.

* – He may, of course, have preferred that the states *not* be entities. But they were, and that was accommodated for in the Constitution he produced. After all, he wasn’t compromising with vapor.

Re “They do not because the only thing that animates them as political entities in the first place are the people who reside within them”

Not true. There are things called borders and they are political borders at that. If one moves from Texas to another state, many things change including not being able to vote in Texas elections. Also the Constitution itself often refers to and specifies powers to the States and any power not given to the federal government belongs to the States.

A Federal Representative often states they are representative of their State or representative of the great people of their State.

Your diagram is inaccurate to. On one side should be the People –District representative – State government with the Governors being elected by all the people of that state.

The federal side should be people-Districts\(50)States- Federal Government. Even the Presidency doesn’t get voted on directly by the people. The people vote through their States which then use the Electoral College.

The winner of the State getting all the electoral vote, sure sounds like the states have their own interest to me. If it was simply the people living in them then the electoral college vote would be split by % of votes the candidates received and would not be broke down by “States”.

It is not a simple matter that all systems are equal as long as people can vote. Why that is even in dispute is amazing.

One should remember the founding fathers knew a simple majority Democracy would be a disaster. They also knew the further away power was moved from the people the less power people will have. That is why they went overboard on the Articles of Confederation. They rectify that by creating the U.S. Constitution. They recognize they needed to give the Federal Government “some” powers but were also still very concerns with State Powers and Individual Rights.

I think the key Madison quote is this one:

The arguments I’ve seen are about which powers belong to the federal government, and which to the states. For a concrete example, the definition of marriage.

In that context, the 9th and 10th Amendments make sense — “these aren’t the only rights the people have” and “if it ain’t listed here, then it belongs to either the states or the people.”

At least, that’s this layman’s reading.

J.

@Trumwill:

And yet, if you read the Notes on the Debate in the Federal Convention what you find is that the construction of what we call federalism was constructed by a series of compromises and decisions that were often debated well apart from one another and that these decisions were made to try and deal with specific political problems and were not based on a grand design of what becomes federalism.

You can likewise see the lack of grand vision when one read the Federalist papers (indeed, the exact way that words like “federalist” are used illustrates this fact, given that the federalists were the ones seeking to strengthen the central government and the anti-federalists were the one arguing for maintaining state power).

@Jay Tea: Yes, there are some powers given to the federal government and some to the states, but the ultimate fount of all of those powers is the people. That would be the most basic point.

@Wayne:

None of which refutes my position. Indeed, your example of moving from Texas to another state changing where your vote counts rather underscores my point: the political power and significance of a state derives, ultimately, not from its stateness, but from the people who live there. This why when you leave you can no longer vote there.

And there is nothing in my argument about who does what–that is, I am not arguing that there aren’t powers given to the states and then to the feds. I am arguing that even the powers given to the states ultimately are linked to the people in the states and that the states themselves are not the unit being represented in an ultimate sense. Take all the people out of a state and all you have is real estate.

And yes, my diagram is simplified, but then again I wasn’t trying to create a diagram of the US government in all its detail, but one that illustrates exactly what Madison was saying in 46.

@Wayne:

No, they wrote the Articles from the perspective of the 13 colonies becoming 13 independent, sovereign countries (i.e., “states”). Treating the states as sovereign co-equals was the problem, and the Articles was not part of the “democracy v. a republic” business.

And yes, the Framers knew we could not have a direct democracy where everyone governed together at once. But, as I have demonstrated on numerous occasions, when Madison used the word “republic” he was referring to the 18th century* version of what we would call “representative democracy.”

*added via edit.

@Steven L. Taylor:

Notes is on my reading list. My main point, though, was that the Constitution was the product of an attempt to thread the needle between those that wanted a stronger, more national government, and those that wanted something that flew closer to the AoC (but with the fundamental change that the states would not be sovereign). And that while the particulars may have been sausagemaking, reserving some powers for the state governments and some for the federal governments was quite intended. Wasn’t it? While recognizing that the overall attempt was moving things towards a more singular national model, there was enough resistance to the notion of a more completely national model, which is why we ended up with a deliberate middle ground between confederate and national: federalism. Correct?

Or are you saying that the federalism was completely incidental? That no one participating wanted to preserve states as distinct political entities? If so, I’d like to see you tackle the creation of the senate the way you tackled the electoral college (which I thought was a great post, btw), so that I have a better idea of where you are coming from.

@Steven L. Taylor:

Take all the people out of a state and all you have is real estate.

Of course, take out all but a dozen and you have real estate, a governor, a (very small) legislature, and most importantly, two senators. 🙂

@Trumwill:

No, I am arguing that a lot of what ends up being federalism was not clearly understood when it was proposed (hence “not grand design”) but resulted from the political back and forth over the question of how to preserve the states as distinct political entities.

Well that was kind of the stated* intention of the Senate, that it’s members would be indirect representatives of the people, while the House would be direct representatives. As was often argued in the Federalist Papers, this added layer of scrutiny would serve as a sort of “filter”, making the members of the Senate a higher quality. The state legislatures, being composed of the highest quality representatives to be had in any given district, would then be more qualified to choose state-wide representatives of the highest quality than a direct election by the people. This was also used (along with their longer terms) to support the Senate’s role in some functions to which the House was excluded, like confirming executive nominees, judicial nominees and treaties.

Moreover, setting aside intent for a moment, there is a very real and practical difference between direct election and appointment by the states. Just as we can have a President elected by a majority of electors, but a minority of voters, so too can a candidate be chosen by a majority of state legislators who would not, perhaps, have been chosen by a majority of the voters in that state. Though this is a very real example of the different nature of representation that existed prior to the 17th amendment, I doubt it’s one that very many people would actual support today.

* “Stated intention” because, like you mentioned previously, the Federalist Papers were an argument after the fact and, like I mentioned at my blog, was not at all what any of the authors had wanted prior to the convention.

Depends on which founder you’re talking about. Hamilton wanted to take away all sovereignty from the states.

@Michael: Yes, but even as an indirect representative body, the fount of all the representation was the people themselves. This is my fundamental point.

Yes, the states were (and are) important. However the only reason the states ultimately matter is because people live in them.

@Michael:

Madison pretty much did as well, at least going into Philadelphia.

Yes, that is the nature of a republic. I was simply making the case that the type of representation that the people would get can be different depending on the mode of selection of the representatives (as the argument has been made that there is no difference in outcome between the pre and post 17th amendment systems).

As to the nature of preserving sovereignty, it’s worth mentioning that the Constitution gives the federal government the authority to “guarantee to every State in this Union a Republican Form of Government”.

@Michael:

Yes: a guarantee to not have aristocracy or the like.

I am not sure what that has to do with sovereignty, per se.

A sovereign state has the authority to choose it’s own form of government. If Mexico decided to adopt a constitutional monarchy, it would have that right. If Texas decided to do the same, even if it otherwise accepted it’s place within the Union and subordinate to the federal government, the federal government would have the right to overthrow that government and replace it with a different one.

@Michael: Excellent point. I thought you were asserting the opposite, which is why I was confused.

@Steven

Re “I am arguing that even the powers given to the states ultimately are linked to the people in the states and that the states themselves are not the unit being represented in an ultimate sense”

That is like saying “even the powers given to a country ultimately are linked to the people in the country and that the country themselves are not the unit being represented in an ultimate sense”.

Yes that is technically true in a “sense”. However a country or a state is more than just its people. It is their real estate\borders, their shared laws, their shared government, etc. A person leaving a state leaves that state community. If it was “only” about being one of the people than that person would be part of that state regardless of where they went. That simply isn’t true.

The people of the world could decide to have one world government with one homogeneous community. They haven’t done that. They are broken up with into nations with their own unique laws and their own governments. The U.S. is broken up in 50 states with their own unique laws and their governments. Many liberals want a homogeneous U.S. and World Government. Just because they wish it that way doesn’t mean it is that way. I for one think it is a terrible idea in practical sense.

Yes there were a few founding fathers that wanted to take away all sovereignty from the states. However there were a shit load more who didn’t. There were many who knew if you did such a thing, the less populated states were be trampled by the more populated states. They purposely design the U.S. Constitution to “help” avoid that.

If the U.S. Constitution would have done away with sovereignty of the states, it would never have been ratified. It wouldn’t even have made it out of the Convention. It disgust me now when people now try to do away with sovereignty of the states and yes they are going against the intentions of the vast majority of our founding fathers.

@Wayne:

A country sans people is Antarctica.

Need I say more?

@Wayne:

But the Constitution did do away with the sovereignty of the states. They became semi-sovereign at best after ratification.

Or are you saying that Texas can have its own currency?

Or that Alabama can declare war on Cuba?

Or that Montana’s legislature can allow its citizens not to pay income taxes to the feds?

Or that California can ratify its own free trade deal with Japan?

Or that New Mexico can open the border with Mexico?

Or that Indiana can declare a monarchy?

I could go on and on and on…

Well, one more:

Or that the South can secede?

Stephen, you have established that people are required for a state or a nation, but not that they are ultimately all that matters.

People without land are not a nation.

People with land but no government are not a nation.

Even people with land and a government are arguably not a nation without external recognition or indifference.

It seems to me that while people are a necessary component for a nation, they are not the only meaningful one. The same goes for states.

Indeed, one has only to look at at the Palestinians for a people with land and a government, yet no nation, no state, no sovereignty.

@Trumwill: Yes, but I would submit that people without and are substantially more important than land without people.

Somehow, for example, the plight of the Palestians is a tad more important than the plight of Antarctica.

@Steven L. Taylor:

The very fact that some believed they retained this right, or the claim to a right of nullification that preceded it, prove that the amount of sovereignty left to the states under the Constitution was never perfectly clear.

Or, should I say, never perfectly agreed upon.

@Steven L. Taylor: Well that depends… land with oil can be pretty important, whether there are presently people there or not. And there are environmentalists that would argue that land without people are important (and should stay without people).

Anyhow, I can get on board with “people are the most important thing” a lot more than people are “the only reason [states/nations/etc] ultimately matter.”

We accord Wyoming more in terms of governance than we do Los Angeles, even though the latter has considerably more people. Beyond land and people, there are also the issues of government and recognition.

@Michael: You might want to see David Hare’s brilliant monologe “Via Dolorosa” in which he addresses the Israeli/Palestinian question through the lens of “what is more important? stones or people?” I believe you can get it through Netflix — it’s troubling and beautiful and everything you would want a great work of art to be.

@Trumwill:

And, yet, the only reason it matters is because of people, whether we are talking about the people who want to exploit the resource or the people who want to protect it.

@Steven L. Taylor:

My main point was in the paragraphs following that one, but forgive a bit more contrarianism.

The fact that people over here care about land over there for selfish reasons doesn’t negate the fact that it’s the land, rather than the people on the land or lack thereof, that is of specific value. Even if nobody lived on Alaska, the land itself would be important without regard to the people that don’t live there.

Now, if your point is “people matter most to people” that’s a true enough statement (except for a certain breed of environmentalist, of course), but not directly relevant to the question of land and people on that land and the land’s value independent of its inhabitants, which can be considerable.

But, again, this is all a side-track. My main contention is the notion that statehood, and nationhood, is defined primarily by people, since there are other necessary-but-not-sufficient factors involved.

@Trumwill: I am not arguing that land is not important. The land upon which my house sits, for example, is rather important to me.

I am arguing that in the scheme of government of the United States that land, simply as land, does not have any political importance despite the way some people argue about the states.

States are ultimately nothing but land under the constitution if there are not people occupying said land. As such, states do not have political interests apart from the people who occupy them.

I reject the notion that states, simply as states, have interests.

Put another way: the only thing that animates the political interests of a state are the people living within said state’s borders.

@ Steven

A country sans land, borders, government is a country that does not exist.

Need I to say more?

Re “But the Constitution did do away with the sovereignty of the states. They became semi-sovereign at best after ratification”

Simply not true. The states still make their own laws and have territorial integrity. Surely you don’t think the U.S. is semi-sovereign because they subject themselves to some international laws. I suspect one day a state or many states will leave the Union once again. It may be the South once again or maybe a single state like California.

California already printed their own currency called IOUs last year. They also have ignored Federal laws.

States also have refused extraditions to other states. They have their own militias. They have refuse cooperate with the Federal Government more than once.

The reason the North gave for declaring war on the South wasn’t the right if the South could seceded or not but the attack on Fort Sumter.

Re “I reject the notion that states, simply as states, have interests”

The fact still remains that the interest of the State of Nebraska is different than the State of New York. The states are “in part” made of people but the States never the less have interest.

@Wayne: “A country sans land, borders, government is a country that does not exist.”

Until they can prove that they have the world’s best egg salad recipe. Then they get a place on the map.

I’d like to think this might be the most obscure movie reference ever posted at OTB…

@Wayne:

Yet, the states are ultimate subordinate to the US central government. This is just a fact (and I noticed you are ignoring my list).

International law is not binding on the US, but US law is binding on the states (it says so in Article VI of the US Constitution). Also: state law is not binding on the US.

Yes, because the people of New York have different interests than the people of Nebraska. The real estate in New York has no interests.