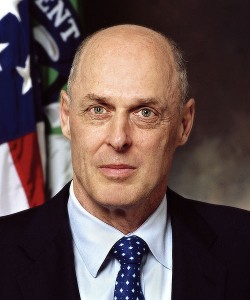

The Lies of Henry Paulson

Buried in the article that James linked in his earlier post about the loophole that essentially eliminates the executive pay limitations of the TARP program is this fun little tidbit:

Lawmakers agreed to the Treasury’s request that the measure apply only to executives at companies whose assets were bought by the government through auctions. In the executive-compensation tax section, a new sentence saying that eventually was inserted.

Meanwhile, Paulson repeatedly told lawmakers that he did not plan to use bailout funds to inject capital directly into financial institutions. Privately, however, his staff was developing plans to do just that, Paulson acknowledged in an interview.

Yes, this is a little tidbit that basically states that Henry Paulson’s testimony before Congress on the necessity of the TARP program was full of lies and misdirections. Quick question: does anybody know if he was under oath when he was requesting this appropriation? If so, how about a perjury charge or two here?

Executive branch officials shouldn’t be able to get away with lying to Congress about how they intend to use requested appropriation money. It’s one thing if circumstances change and adaptation is required. It’s quite another to ask for money for one program when you’re planning to use it for a different purpose the whole time.

h/t Steve Benen

It’s a fair question. As you likely recall, Paulson’s original proposal amounted to “Give me the damn money and shut up.” When Congress balked, he basically talked them into a bill that gave him wide latitude within hazy parameters. But things like the GM bailout are so tangentially related to even that vague purpose that I don’t see how he gets away with it.

Uh huh.

And I’m sure if you look somewhere in the Penegon there resides operational battle plans for wars to be waged against every country on the planet.

My guess is, we won’t execute such plans.

Bit: But Paterson has already done just that and is now planning to circumvent Congress and give money to the Big 3 auto companies. Almost as soon as Congress approved TARP, Paulson and Company decided that they wanted to spend it in an entirely different way than they’d told Congress they would.

It never ceases to amaze me that people are astonished when government actually doesn’t live up to their expectations of some sort of benevolent entity. I also like it when people learn that government is like many other entities–i.e. is concerned about its own self-preservation and prosperity and will pursue those ends just as vigorously as most other entites (i.e. corporations).

But what the heck…lets give it just one more go…and if we find just the riiiiight person…well everything will be fine.

So you’re saying we shouldn’t be upset when things like this happen? Or was this just an opportunity to insult both the government and anybody who is less cynical than you?

But if they were planning to executing one of those plans, while simultaneously telling Congress that they were not planning on executing that very plan, that it was in fact only a measure of last resort….oh wait, nevermind.

You’re right, lets not give it another go, forget this whole government thing, it’s time to try…..what exactly? What do we do that isn’t “one more go” Steve?

Seems to me that Paulson and Bernanke saw that a total economic collapse needed to be avoided and the initial solution was to buy troubled assets. Congress gave treasury up to 700 billion with some wide latitude as to how it would be used. But the purpose was always clear, ie. head off widespread economic calamity.

While we can always disagree on the details it seems to me that the money did what it was supposed to do. The banking sector is still intact and engaging in economic activity remains possible across all economic sectors.

Republicans are usually not worth defending but Paulson’s actions are easily defensible. He did the big thing right. He got a lot of secondary things wrong due to his conservative ideology but all and all he kept the financial system, and along with it the entire economy, from total collapse.

To be fair to Paulson, as the congressional approval was in the air a great number of economists started raising questions about how the original TARP could work.

The basic question (how could you buy assets cheap enough to make them an reasonable government investment, but high enough to refloat the banks?) had merit.

The original argument, that we could buy these things cheap, bail out the banks, and recover taxpayer monies seemed to have collapsed.

So what to do?

Many economists liked the “buy equity” path. They liked it as implemented in Britain. So some shift by Paulson may have been expected.

Perhaps also they expected him to drive a better deal.

Yep. This is what happens when you have a discretionary government.

I prefer the rules rather than discretion approach.

In other words, the idea that we can have a government that engages in discretionary policy has been around well past its expiration date. It is time to rethink this idea that we can elect just the right person each and every election to make things just right. There is a fairly long list of reasons why voting is a pretty bad way for setting policy.

Add Steve Verdon to your list of communo/fascist/dictatorship sympathazing libertarians…

And before you jump all over me Steve, do you have a better way to run a country?

Yes, read the link. All the way to the end this time, especially the second paragraph on page 487. Then you might want to look at their follow up article. Read through Bryan Caplan’s book Myth of the Rational Voter, and also take a look at some of the stuff by Gordon Tullock and James Buchanan.

Basically we want to move away from majority rule as a policy setting device. It doesn’t mean a dictatorship though as that wouldn’t solve the problem either. We need to reduce the ability of politicians to fiddle around with policy, not increase it.

Oh, and engage your brain.

But if we move from discretionary to rule based, who will determine the rules? How will we allow them to be changed? How much and how frequently will we allow them to be changed? Who will determine when exceptions to the rule should be made, and how will they determine it? One way or the other, you get back to either democracy or dictatorship.

No, but voting is the best way of unsetting policy, and that is why it is still important.

Another Rip Van Winkle asleep for the past eight years. And someone should find a fainting counch for this blog’s writers. They’re stunned that a Bush Administration official has lied to Congress.

1. Determining the rules is the tricky part. Obviously politicians would be involved in this and we’d be asking them to basically limit their own power. In other words, good luck here.

2. As for changing them, you could use super-majority rules or other difficult but not impossible ways to indicate level of commitment to a given policy.

There are two things to keep in mind here.

1. Rules don’t have to be simple, they can be somewhat sophisticated, hence the reference to Kydland and Prescott’s follow-up article.

2. You don’t want to change them if possible as that is where you run into commitment problems.

Again, you don’t want to do this so you’d want such changing things and “exceptions” difficult or rare. Making it easy/common means there is little or no commitment and you are back to the sub-optimal outcome.

Lets knock off this goddamned freaking bravo sierra about dictatorship, mkay? I mean really, what kind of moron thinks a libertrain leaning person is going to favor dictatorship. There is only one rule under dictatorship and it goes like this, “One man, one rule.” In other words, one person makes the rules and can change them at his whim. This is 180-fricking-degrees from what I’m writing about.

As for democracy, yes, but please note my previous comment, “We need to reduce the ability of politicians to fiddle around with policy, not increase it.”

And yes, I realize that this is not going to be easy and possibly even impossible given that we are dealing with venal politicians who often have no backbone. But tom p asked if I thought there was a better way. Yes I think there is, and I’ve outlined it somewhat roughly. But the short comings of our politicians makes this better way difficult to achieve at best. Hence my cycnicism regarding politicians…of all viewpoints. I don’t think Democrats or Republicans are all that different and I despise them both.

And as long as our politicians are elected by majority vote, then a our policy will still be determined by a majority vote, which you’ve already stated will produce suboptimal results.

I see where you’re going with this, but requiring a super-majority to get anything done sounds like the making of a system where everything stays suboptimal, but nobody can be held responsible for it.

But the more detailed a rule is, the narrower it’s application will be, which means we would need ever more rules to cover every application, which increases the likelihood of establishing suboptimal rules that will be difficult to correct.

Why is commitment good, other than for the application of control theory?

But when there is little or no commitment, the lifespan of a sub-optimal policy is much shorter.

Sorry, I meant that in a much more generic way, that either the rules are established by a popular vote (which you said results in suboptimal policy), or the rules are established by a minority who unilaterally declare the rules (which I gather you would oppose).

I see that you’re advocating a weak democracy, where changes in policy are few and far between, but you still have not addressed how it is that we should establish optimal rules at the beginning, rather that establishing suboptimal ones? If we can’t guarantee optimal rules from the onset, and we can’t hold our elected officials accountable for their continuation, what forces would ever cause a change in the rules?

No, the system with discretion will always be sub-optimal and even with supre well intentioned politicians who are complete dedicated to serving the “public good”.

As such, the use of rules is to move to a better outcome, maybe not optimal, but better than the policies under discretion.

It is a question of trade-offs between simpler more broadly applicable rules, and narrower sophisticated rules. It isn’t perfect, then nothing in this world is.

Without a commitment mechanism you wont be able to achieve the better policy outcome. The problem is that forward looking actors will realize the policy maker will have an incentive to deviate. For example in the inflation/unemployment trade off model, the optimal policy is to hold inflation to zero. If consumers and firms believe this then you can get an increase in welfare by increasing inflation at a later date and reducing unemployment. However, without commitment these consumers and firms will realize this and when you go to increase inflation you get no boost in employment and higher inflation, clearly the less preferred outcome.

But you can never achieve the optimal, so what? So you have a sequence of sub-optimal outcomes. I don’t see why this is preferred.

I didn’t say it would be easy. Establishing the rules will probably be the hardest part since as you pointed out it will be the result of the democratic process. As far as I know there is little or no comprehensive answer to this part of the problem. However, these kinds of things have happened piece-meal. Here in California a super-majority of votes is needed to raise taxes. This is of course one reason why CA is having budget issues. Also there was Prop. 13 in CA that limited the State’s ability to raise property taxes. The latter was more of a grass roots/voter revolt kind of thing.