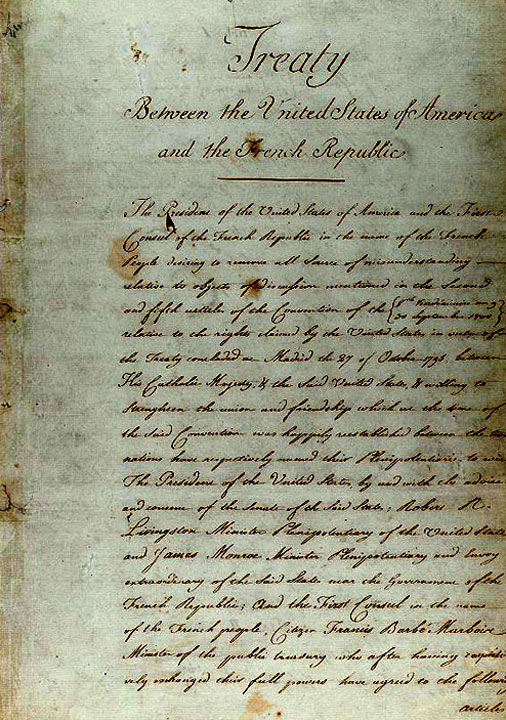

TREATIES AND SUCH

My earlier post has now gotten Steven involved.

I’ve done some more research into the Executive Agreement and treaty processes. The Senate‘s home page gives quite a bit of information on this issue:

Executive Agreements In addition to treaties, which may not enter into force and become binding on the United States without the advice and consent of the Senate, there are other types of international agreements concluded by the executive branch and not submitted to the Senate. These are classified in the United States as executive agreements, not as treaties, a distinction that has only domestic significance. International law regards each mode of international agreement as binding, whatever its designation under domestic law.

The difficulty in obtaining a two-thirds vote was one of the motivating forces behind the vast increase in executive agreements after World War II. In 1952, for instance, the United States signed 14 treaties and 291 executive agreements. This was a larger number of executive agreements than had been reached during the entire century of 1789 to 1889. Executive agreements continue to grow at a rapid rate. The United States is currently a party to nearly nine hundred treaties and more than five thousand executive agreements.

The growth in executive agreements is also attributable to the sheer volume of business and contacts between the United States and other countries, coupled with the already heavy workload of the Senate. Many international agreements are of relatively minor importance and would needlessly overburden the Senate if they were submitted to it as treaties for advice and consent. Another factor has been the passage of legislation authorizing the executive branch to conclude international agreements in certain fields, such as foreign aid, agriculture, and trade. Treaties have also been approved implicitly authorizing further agreements between the parties. According to a 1984 study by the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, “88.3 percent of international agreements reached between 1946 and 1972 were based at least partly on statutory authority; 6.2 percent were treaties, and 5.5 percent were based solely on executive authority.”

Washigton Trade Reports, a group with which I’m unfamiliar, has a very long essay on this issue that looks authoritative. Not knowing their bonafides makes me reluctant to endorse it more fully than that. Their summary of the history, however, comports with my impression:

During 1789-1839 the United States reached an average of just 1.7 international agreements per year, of which only 31.0 percent were executive agreements. By 1980-1990 the pace increased to 402.1 agreements per year, 95.8 percent of which were executive agreements. [Calculated from data in Lindsay, op.cit., page 82.] The growth of executive agreements was also facilitated by the Supreme Court̢۪s increasingly expansive view of executive authority and the constitutionality of delegated power.

This essay does a good job of differentiating between true executive agreements, executive-legislative agreements, as well as those pre-approved by Congress versus those submitted after the fact. Those submitted under Fast Track/TPA are technically executive-legislative agreements with prior legislative authorization. The chief advantage of this system, from the Congress’ perspective, is that it forces presidents to work with the legislature throughout the process rather than submitting the completed treaty as a fait accompli; hence the Senate’s willingness to suspend its Constitutional 2/3 approval power.

Griffith Bell has an interesting essay on the subject in which he argues that executive agreements and executive orders are just a natural part of the ambiguity of the Constitution, rather than a real sidestepping of it. He’s probably right on this. As much as I like Strict Construction as an abstract concept, it’s almost impossible to govern a 21st Century superpower while strictly following a 18th Century Constitution.

There is a useful reference guide compiled by the University of California-Berkeley listing all treaties in force. A lot of presidential documents, including links to executive agreements, can be found at this site compiled by a professor The University of North Texas.

Update (15:15) Brett supplies this review of a book by Bruce Ackerman and David Galove.

Those stats are quite interesting.

Great post.

How do you know constitutional ambiguity and functional necessity when you come across it? This is an important question and opens the door to the death of “strict construction” as binding rather than as a rule of thumb (one among many), in my view.

Brett,

No doubt. While most of the time, Strict Construction is used as an argument against the courts making up new law, it is problematic on occasion. If the Supreme Court were to knock down every action of the legislature that violates the letter of the Constitution, we’d definitely need to amend the Constitution a lot more. That may be a good thing. But it’s clear that a strictly construed 1789 document isn’t practical in all instances.

I agree with what you say. The question of whether or not to apply “strict construction” is, then, a matter of political judgement. That’s not what you hear from a lot of people who defend “strict construction.” What you generally hear is that people who don’t hold to whatever view of constitutional interpretation that this is supposed to represent are “making law” rather than interpreting it. But what you’re saying here, if I understand you correctly, is that there is no “strict construction internal” account of when to apply “strict construction” itself. That strikes me as very important, and it certainly takes away a lot of the thunder of people who pound on the table when you advance a different view of constitutional interpretation.

Brett,

I agree. I see a legitimate distinction between an activist judiciary striking down laws based on a made-up Constitution, such as sewing together a right of privacy from loose strands of the document, and a judiciary that allows the elected branches some leeway in how they handle things in the gray areas of the Constitution. To use a sports analogy, it’s better for the umpires to “let the players play” rather than injecting themselves too much into the game and calling the ticky-tack fouls. On the other hand, we don’t want umpires making up their own strike zone.

But, I agree, from a purely philosophical standpoint, there’s little real difference.

Jim:

I like the strike zone analogy, partly because everyone knows that umpires do vary their strike zones slightly, and pitchers and catchers know this as well (that’s why pitchers like Greg Maddux test the outside edge when they start). If you just stared at the rule book, you wouldn’t be able to account for the actual practice of calling strikes. Plus, the american league umpires call a different strike zone from the national league umpires, and players rarely complain about this; indeed, they adopt their styles to the differences — that’s why the Braves starters like to throw low and away a lot of the time, while that strategy wouldn’t help as much in the narrower and taller American league strike zone. That’s as it should be; it’s an inevitable part of a game played and judged by human beings.