13-Year-Old Defeats Tetris (Sort Of)

James T. Kirk would be proud.

When I saw the AP headline “13-year-old gamer becomes the first to beat the ‘unbeatable’ Tetris — by breaking it,” my mind immediately went to Cadet James T. Kirk’s famous response to the Kobayashi Maru training simulation at Starfleet Academy by changing the conditions of the test.

Alas, it was something both more benign and, in some ways, more remarkable:

The falling-block video game Tetris has met its match in 13-year-old Willis Gibson, who has become the first player to officially “beat” the original Nintendo version of the game — by breaking it.

Technically, Willis — aka “blue scuti” in the gaming world — made it to what gamers call a “kill screen,” a point where the Tetris code glitches, crashing the game. That might not sound like much of a victory to anyone thinking that only high scores count, but it’s a highly coveted achievement in the world of video games, where records involve pushing hardware and software to their limits. And beyond.

It’s also a very big deal for players of Tetris, which many had long considered unbeatable. That’s partly because the game doesn’t have a scripted ending; those four-block shapes just keep falling no matter how good you get at stacking them into disappearing rows. Top players continued to find ways to extend their winning streaks by staying in the game to reach higher and higher levels, but in the end, the game beat them all.

Until, that is, Willis managed on Dec. 21 to trigger a kill screen on Level 157, which the gaming world takes as a victory over the game — something along the lines of pushing the software past its own limits.

The makers of Tetris agree. “Congratulations to ‘blue scuti’ for achieving this extraordinary accomplishment, a feat that defies all preconceived limits of this legendary game,” Tetris CEO Maya Rogers said in a statement. Rogers noted that Tetris will celebrate its 40th anniversary this year and called Willis’ victory a “monumental achievement.”

It’s been a very long road. Early on, “the Tetris scene people didn’t even know how to get to these higher levels,” said David Macdonald, a gaming YouTuber who has chronicled the gaming industry for years. “They were just stuck in the 20s and 30s because they just didn’t know techniques to get any further.” Level 29 posed an especially tough roadblock because the blocks began falling more quickly than the in-game controller could respond.

Eventually players found ways to make progress, as Macdonald chronicled in his detailed video on Willis victory. In 2011, one got to Level 30 using a technique called “hypertapping,” in which a player could rhythmically vibrate their fingers to move the game controller faster than the game’s built-in speed. That technique took players to level 35 by 2018, after which they hit a wall.

The next big thing came in 2020 when a gamer combined a multifinger technique originally used on arcade video games with a finger positioned on the bottom of the controller to push it against another finger on the top. Called “rolling,” this much speedier approach helped one player reach Level 95 in 2022.

Then other obstacles arose. Because the original Tetris developers had never counted on players pushing the game’s limits so aggressively, bizarre quirks began to crop up at higher levels. One particularly difficult issue arose with the game’s color palette, which traditionally cycled through 10 easily distinguished patterns. Starting at level 138, though, random color combinations began to appear — some of which made it much harder to distinguish the blocks from the game’s black background.

Two particularly devilish patterns — one a dim combination of dark blues and greens later dubbed “Dusk,” the other composed of black, gray and white blocks called “Charcoal” — proved taxing for players. When combined with the strain of increasingly longer games, which could run 40 minutes or more, progress slowed again. It took a Tetris-playing AI program dubbed StackRabbit to break that logjam by helping map out just where players might happen across a glitch resulting in a kill screen, and finally beat the game.

StackRabbit, which managed to make it all the way to Level 237 before crashing the game, ran on a modified version of Tetris, so its achievements aren’t strictly comparable to those of human players. And its findings weren’t immediately applicable to the human-played game, either. But its runs clearly demonstrated that game-ending glitches could be triggered by very specific events, such as which block pieces were in play or how many lines a player cleared at once.

That let human players take over the task of mapping all possible scenarios that could cause such crashes in the original game. These typically resulted when the game’s decade-old code lost its place and began reading its next instructions from the wrong location, generally resulting in garbage input. A massive effort spurred by StackRabbit’s experience eventually led to the compilation of a large spreadsheet that detailed which game levels and which specific conditions were most likely to lead to a crash.

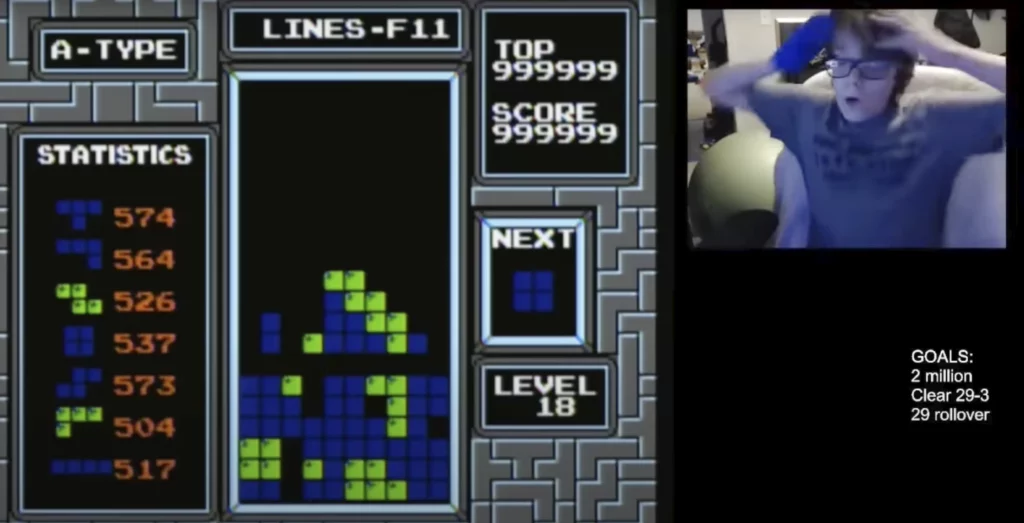

That’s what compelled Willis to make his run for the record. Yet even he appeared shocked when he crashed the game at Level 157. In his livestream video, he appears to hyperventilate before barely gasping “Oh my God” several times, clutching his temples and worrying that he might be passing out. After cupping his hands over his mouth in an apparent attempt to regulate his breathing, he finally exclaims, “I can’t feel my fingers.”

This is remarkable to me in many ways.

That a game designed four decades ago is something of a perpetual motion machine is just stunning. As is the fact that a game with comparatively bad graphics and simple gameplay is still captivating people all these years later.

The sheer human endurance required to maintain concentration through 157 levels of a game, some of them essentially blind, is extraordinary.

It’s also a monument to human cooperation that, through the ever-advancing tools of the information, Tetris players have shared enough knowledge to help the community learn to navigate these levels. It would have been simply impossible for someone—much less a 13-year-old—to play the game enough on their own to figure out the thousands of idiosyncracies required to get through so many levels of a constantly-evolving game.

I was in Edinburgh on book tour (with a side order of single malts), walking down the hill toward the New Town when my publicist and I came across a street band playing bagpipes. An energetic, somehow Slavic tune that we both recognized but could not place. Later the penny dropped: the Tetris music, but with kilts. Even the music has endured for decades.

The backstory on Tetris is fascinating.

BBC did a documentary several years ago: Tetris – From Russia With Love.

Tetris has also been extensively research in the psychological and brain sciences. The wiki page summarizes some of it.

It was the first game I played on Nintendo Game Boy. I’ve never been a gamer, but it made long car rides to soccer tournaments that much more bearable. I’ve not played in years.

Hat tip to the denarian player for the achievement. And to the quinquagenarian blogger for posting on it.

Part of the game’s longevity is probably related to the “Tetris effect”. There’s something about the game that resonates deeply with some core part of the human cognitive cycle.

Most interesting application is that playing Tetris for a twenty minutes within six hours of a traumatic event appears to provide a prophylactic effect that prevents the development of PTSD:

How Tetris therapy could help patients

Wife and I were Tetris addicts during Desert Storm. We would compare scores when we got a chance to talk and talk over strategies. It gave us something to do while we were apart. She gave it up when she started getting hand and shoulder issues from playing too much so I quit also. I thought the game had kind of faded away but happy to hear that it has persisted and i am honestly surprised anyone was able to crash it. Kid must have incredible hand skills.

Steve

@Mimai:

Apple did a surprisingly good movie dramatizing the backstory of Tetris last year:

Tetris — Official Trailer

Never had the hand-eye coordination to play Tetris past level one. Good thing I’ve never n needed PTSD treatment, I guess.

As a software nerd, the coolest part of this story (to me!) is just how the system breaks.

The color schemes go crazy because the location it looks for colors is bounded by a specific set of bits – but the color scheme selector overruns that set past Level 29 (10 levels past the last “speed-up” level, since that’s all the colors they thought they would need!) and the generated colors are entirely predictable but also very strange. There are also levels where it takes more lines – sometimes a lot more lines! – to advance, because the internal system is subtracting two numbers but one of the numbers has rolled over, so it comes up with something absurd like 300 lines to advance. The breakage this kid hit is a single-line score computation, because rather than implement multiplication, it was more compact for the designers to implement “serial addition” up to the level; on Level 157, that’s a lot of adds and if the next game action tries to come in before it can be completed, the entire game freezes.

What’s incredible to me is how cartridge game designers cut corners to fit all the content in the allotted memory space. Things like calculation of the location of Mario in SMB that let people do speed runs, or the level designs in Pitfall!, or even the Street Fighter II fix of the name “World Warrier” using the extant sprite sheet.

(For the record, I’ve gotten up to Level 21, starting on 19, by somehow slamming a pair of Tetrises at the right time. It was total dumb luck. At the time, I could regularly advance to 20, but the speed increase at 20 is brutal for an old-school player like me.)

One reason I’m not terribly worried about AI.