DOD Won’t Fund Promising PTSD Treatment

Anesthesiologist Eugene Lipov thinks he has found a cheap, effective treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder. The Army won't fund it.

Anesthesiologist Eugene Lipov thinks he has found a cheap, effective treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder. The Army won’t fund it.

Megan McCloskey, Stars and Stripes (“Doctor: PTSD injection can work miracles, but DOD won’t fund it“):

In 2007, the Chicago-based Lipov discovered that injecting a local anesthetic into a bundle of nerves in the neck of war veterans relieved PTSD symptoms. One, or sometimes two injections, and the veterans were suddenly better.

Lipov has tried three times in the last four years to get the Department of Defense to fund a study on the treatment, but even with an endorsement of then-Sen. Barack Obama, he hasn’t been able to wrench open the government pocketbook. The best he’s been able to do is convince two Navy doctors in San Diego to do a small study of their own.

“You would think the government would look at the results I’ve had and say, ‘This is a great idea. How can I help you?'” Lipov said. “But I’m still waiting.”

[…]

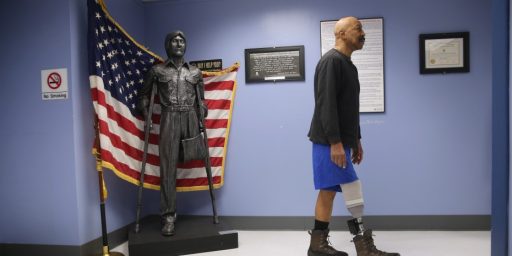

Lipov says his 12 patients have shown the shot to work, and in 2009, an Army doctor replicated those results with two soldiers at Walter Reed Army Medical Center. Lt. Col. Sean Mulvaney’s results were published in the Pain Practice journal, where he wrote that both of his patients with chronic PTSD “experienced immediate, significant and durable relief.” Mulvaney has now treated 15 patients with the shot.

The testimonials of many of the veterans and servicemembers are powerful. The nightmares, flashbacks, anger and other PTSD-related issues were gone, they said, replaced with a calm they hadn’t felt in years.

Still, with those who hold the purse strings in the military research community, it’s been a hard sell for an outsider like Lipov. The 10-minute procedure has been used since 1925 to treat pain, so it isn’t a new concept. But no one before has proposed that it could treat PTSD, which despite its physical manifestations in the brain, is still largely thought of as an emotional problem.

Lipov and his supporters say this is bureaucracy at its worst, rejecting a novel treatment from an outsider. But the Army’s explanation seems perfectly reasonable:

The U.S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command at Fort Detrick isn’t buying it. Last month, they rejected Lipov’s latest proposal, a $1.6 million clinical trial.

Reviewers of the proposal acknowledged that should a randomized controlled trial prove successful, it “could lead to important innovations in the medical treatment of PTSD.”

But they wrote in their scientific review that they were concerned Lipov’s study was overly ambitious and expensive for a relatively untested concept — and one they think lacks a convincing neurobiological explanation for why it works.

Even a psychologist who has signed on to help advise Lipov as he moves forward with his work, agrees with the reviewers on that note.

“You have to start with a theory that makes sense to folks,” said Stevan Hobfoll, who heads the Department of Behavioral Sciences at the Rush University Medical Center in Chicago.

Col. Carl Castro, director of Ditric’s Operational Medicine Research Program, said Lipov skipped an important step: a study with control groups. Without that, the scientific community looks at results as little more than fallible anecdotes.

The Army, which spends about $30 million a year on PTSD research, would like to explore Lipov’s approach, but he “needs to do a scientifically rigorous study, and that way if he gets promising results, we can be confident in doing a much larger clinical trial,” Castro said. “We don’t want to fund a study that has the possibility of failure, or has findings that will be so ambiguous we won’t know what to make of the findings. It’s a novel concept and really we have just got to ensure that what we’re doing is safe and actually does what the treatment is supposed to do.”

There’s an old joke about a doctor who has come up with a miracle treatment and is presenting his success story. A questioner asks him if he’s using a control group and the doctor huffs, “No! I’m not going to kill half my patients!” The questioner retorts, “Ah, but which half?”

One hopes Lipov’s treatment works. PTSD is rampant in those who have suffered the stress of multiple deployments over the past decade. But there’s a reason medical research protocols exist. That a handful of patients who have been desperate enough to try Lipov’s treatment are feeling better doesn’t really tell us much. Maybe they’re experiencing a Placebo effect. Maybe the injection itself provides temporary relief but has yet-unknown side effects. There needs to be a sound basis for moving forward and then careful, controlled research to figure out these things.

One sentence jumped out at me:

“You have to start with a theory that makes sense to folks,” said Stevan Hobfoll, who heads the Department of Behavioral Sciences at the Rush University Medical Center in Chicago.

I cannot disagree enough with this sentiment. So many discoveries have been counterintuitive. My favorite example is “we got hyperactive kids. We need to calm them down and help them focus. Let’s give them stimulants!”

Perhaps the good doctor’s plans were a bit too ambitious, but his positive results deserve further investigation.

J.

Sometimes things that have been done for a long time aren’t always the right thing, but more often, if its been used this long its side effects are benign (or at least known).

Even without out a study what prevents people with PTSD from seeking this treatment? Cost? If its a few hundred or even a few thousand the out of pocket cost seems worth it. If its more than that I can understand why people would want it covered as part of their health care coverage. Of course Insurance companies will balk at the cost at least until it becomes an “approved” treatment. (A doctor assuming the ‘liability’ for an unapproved procedure is probably also a deterent.)

This quote from the article probably explains it more. This is a budgeted amount that is already spent, or being spent. It wouldn’t necessarily increase for this study, instead Lipov’s study would cut into someone elses pet project (i.e. study money)

In all seriousness, if I were the doctor, I’d contact Jon Stewart (see, Christopher Buckley, Jon Stewart, Live at the USO).

@samwide: Let’s toss in Congressmen Ron Paul and Allen West — say what you want about those two gentlemen (and I’m on record as saying that Paul is several kinds of crazy), they’re serious about veterans’ affairs.

J.

“We don’t want to fund a study that has the possibility of failure…”

Some real cutting-edge research these people must be doing.

This is patently ridiculous. It is not scientific research that they are funding if their selection criterion is that the study cannot fail.

@rodney dill:” Lipov’s study would cut into someone elses pet project ”

And it wouldn’t be simply a treatment project; as I understand it, DOD has been doing a lot of research in preventive measures (particularly around concussions) and getting soldiers diagnosed earlier and in treatment.