Does Privacy Still Exist?

When everyone can record video at any time and post it to for all the world to see, is there such a thing as privacy anymore?

When everyone can record video at any time and post it to for all the world to see, is there such a thing as privacy anymore?

Brian Stelter for NYT (“Upending Anonymity, These Days the Web Unmasks Everyone“):

Not too long ago, theorists fretted that the Internet was a place where anonymity thrived.

Now, it seems, it is the place where anonymity dies.

A commuter in the New York area who verbally tangled with a conductor last Tuesday — and defended herself by asking “Do you know what schools I’ve been to and how well-educated I am?” — was publicly identified after a fellow rider posted a cellphone video of the encounter on YouTube. The woman, who had gone to N.Y.U., was ridiculed by a cadre of bloggers, one of whom termed it the latest episode of “Name and Shame on the Web.”

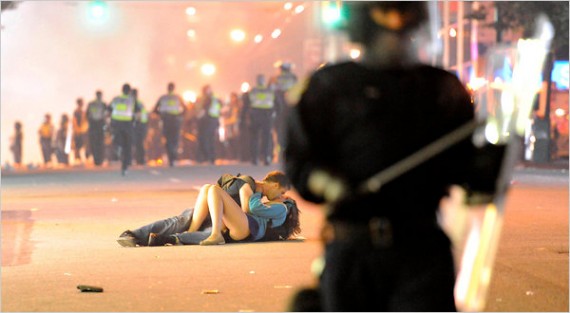

Women who were online pen pals of former Representative Anthony D. Weiner similarly learned how quickly Internet users can sniff out all the details of a person’s online life. So did the men who set fire to cars and looted stores in the wake of Vancouver’s Stanley Cup defeat last week when they were identified, tagged by acquaintances online.

The collective intelligence of the Internet’s two billion users, and the digital fingerprints that so many users leave on Web sites, combine to make it more and more likely that every embarrassing video, every intimate photo, and every indelicate e-mail is attributed to its source, whether that source wants it to be or not. This intelligence makes the public sphere more public than ever before and sometimes forces personal lives into public view.

To some, this could conjure up comparisons to the agents of repressive governments in the Middle East who monitor online protests and exact retribution offline. But the positive effects can be numerous: criminality can be ferreted out, falsehoods can be disproved and individuals can become Internet icons.

[…]

This erosion of anonymity is a product of pervasive social media services, cheap cellphone cameras, free photo and video Web hosts, and perhaps most important of all, a change in people’s views about what ought to be public and what ought to be private. Experts say that Web sites like Facebook, which require real identities and encourage the sharing of photographs and videos, have hastened this change.

[…]

This growing “publicness,” as it is sometimes called, comes with significant consequences for commerce, for political speech and for ordinary people’s right to privacy. There are efforts by governments and corporations to set up online identity systems. Technology will play an even greater role in the identification of once-anonymous individuals: Facebook, for instance, is already using facial recognition technology in ways that are alarming to European regulators.

After the riots in Vancouver, locals needed no such facial recognition technology — they simply combed through social media sites to try to identify some of the people involved, like Nathan Kotylak, 17, a star on Canada’s junior water polo team. On Facebook, Mr. Kotylak apologized for the damage he had caused. The finger-pointing affected not only him, it affected his family: local news media reported that his father, a doctor, had seen his ranking on a medical practice review site, RateMDs.com, drop after people posted comments about his son’s involvement in the riots. Other people subsequently went to the Web site to defend the doctor and improve his ranking.

[…]

“Publicity” — something normally associated with celebrities — “is no longer scarce,” Dave Morgan, the chief executive of Simulmedia, wrote in an essay this month. He posited that because the Internet “can’t be made to forget” images and moments from the past, like an outburst on a train or a kiss during a riot, “the reality of an inescapable public world is an issue we are all going to hear a lot more about.”

It’s almost certainly a good thing that rioters can now be more easily prosecuted, having lost much of the anonymity of the mob. It’s less clear that a subway commuter having a bad morning should be subject to national ridicule and be part of the “permanent record” of the Internet. But these are facts of modern life.

@James:

National ridicule is only fitting for people unable to be quiet in “quiet cars”.

Loud Cell Phone Talker Arrested.

Maybe that woman had a bad morning too?

Well, it was a bad morning that stretched on for several hours and led to her being dragged away by police. But I’m not sure that it deserves to be made a viral internet sensation. Once that happens, though, there’s not much point in pretending it’s not out there.

I’m not on Facebook. Can I sue them for using my image without my consent? At the very least, images of me when I’m not in a public place, as most of the above examples are.

(Just curious; it’s my next get-rich-quick scheme. 🙂

This is only a new phenomena here. Anyone following the net in Asia has heard of the Human Flesh Search Engine and its pernicious mob mentality effects. That Metro North video was reminded me of the “Bus Uncle” video that went viral in Hong Kong a few years back (along with the subsequent “Airport Auntie” tantrum at Hong Kong’s airport).

Privacy is a recent concept. In village life and tribal life there was no privacy. In clans and extended families there was none. So for most of human history everyone knew everyone else’s business.

It’s not that the internet is destroying privacy, since the cited incidents were very much public. What the internet does is make permanent and widely available those incidents that had previously been limited to the memory of those who directly observed it.

As @MR and @Michael have both suggested what internet and new media technologies have primarily done is alter the speed, scale, and scope of “gossip.” Privacy, as we understand it is largely a modern and western idea.

The other big change is that in the past, one could reinvent themselves through travel — going to where they are not known. This was one of the reasons that prisoners and deserters were often explicitly or implicitly branded (either literally or through the removal of body parts) — so that no matter where they went people knew their past.

The other thing to remember is that norms are always in flux and always in dialog with a whole bunch of factors including technology. As has been seen with changes in phototagging practices on Facebook, new norms will develop that will create a new sort of “privacy” — or at the very least, less concerns about certain types of past behavior.

http://www.peopleofwalmart.com

’nuff said.