Frozen Russian Assets to Fund Ukraine War

It's about time.

An interesting story has been brewing the last few days. The first shoe dropped Tuesday:

Euractiv (“Council of Europe unanimously votes to use seized Russian assets to fund Ukraine reconstruction, compensation“):

The Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (CoE) unanimously adopted a resolution on Tuesday (16 April) calling for frozen Russian assets to be transferred to a new fund to reconstruct Ukraine and compensate victims.

The Russian government should be held responsible for compensating the human and material losses incurred and “its destruction of Ukraine”, rapporteur for the file, Lulzim Basha (Albanian Democratic Party, EPP) said upon opening of the body’s session.

Basha’s resolution, adopted with 134 votes in favour and no abstentions or opposition, states the seized Russian assets should be used to compensate natural and legal persons for damages caused by Russia’s acts that have accompanied its illegal invasion.

“Today we vote to endorse the establishment of an International Compensation Mechanism, under the auspices of the Council of Europe, to comprehensively address the damages incurred by natural and legal persons concerned […] due to the unlawful actions of the Russian Federation in its invasion of Ukraine,” Basha said.

The mechanism, he said, would be given the authority and capacity to receive and review claims from Ukraine and other damaged parties — public and private — and distribute appropriate compensation for such claims in line with internationally agreed standards and procedures.

It would complement the register of damage caused by Russia’s aggression against Ukraine, already created by the body

“Third states, that is, states that have not been directly injured by the offending state’s conduct, are permitted by international law to take collective countermeasures against the offending state, in this case Russia, for grave breaches of its obligations,” Basha said.

Russia has received plenty of warnings and requests to desist “It is overdue to take the next step”, the rapporteur noted, calling on CoE member states to cooperate fully with the prompt transfer of assets to the mechanism and fund.

This is part of a larger effort that has been talked about for some time.

The Economist (“Frozen Russian assets will soon pay for Ukraine’s war“):

After Russia destroyed the Trypilska power plant on April 11th, Ukraine blamed a lack of anti-missile ammunition. The country’s leaders are also desperate for more financial support. The two shortages—of ammunition and money—reflect different constraints among Ukraine’s allies. Whereas the lack of ammunition is mostly the product of limited industrial capacity, the lack of money is the product of limited political will.

In one area, though, there are signs of progress: over what to do with Russia’s frozen assets. After Vladimir Putin invaded Ukraine, Western governments quickly locked down €260bn-worth ($282bn) of Russian assets, which have remained frozen ever since. Proposals about what to do with them have ranged from the radical (seize them and hand them over to Ukraine) to the creative (force them to be reinvested in Ukrainian war bonds). Until recently, none has found widespread favour with Western governments.

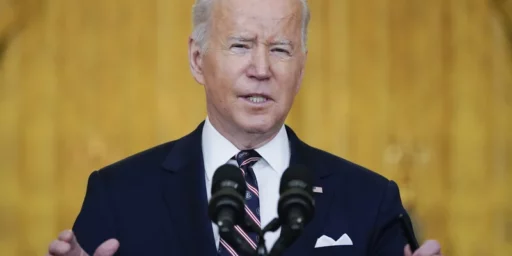

Could that soon change? On April 10th Daleep Singh, America’s deputy national security adviser for international economics, declared that the Biden administration now wanted to make use of interest income on frozen Russian assets in order to “maximise the impact of these revenues, both current and future, for the benefit of Ukraine today”. Six days later David Cameron, Britain’s foreign secretary, announced his support, too: “There is an emerging consensus that the interest on those assets can be used.”

The approach is an elegant one. Income earned on Russia’s foreign holdings can be seized in a manner that is both legal and practical. Many of the country’s bonds have already matured. Cash from redemption of bonds is held by the depository in which it currently sits until it is withdrawn, paying no interest to the owner as per the depository’s usual terms and conditions. Any interest earned thus belongs to the depository—unless, that is, the state decides to tax it at a rate close to 100%.

Next, as suggested by The Economist in February, would be to transfer the net present value of that income stream to Ukraine. Investing Russia’s cash holdings into five-year German bunds would yield €3.3bn a year, enough to service eu debt of about €116bn at the same maturity. The rest is financial plumbing: set up a G7-guaranteed fund that receives the depositories’ incomes on Russian cash, issue that fund’s debt to the markets and send the proceeds in bulk to Ukraine.

Although the eu has agreed to seize profits from depositories, it has not agreed to the subsequent steps. Under the bloc’s current plans, the proceeds will be used to pay for Ukrainian ammunition by July if all goes well, with a small portion set aside to compensate depositories for any Russian legal action or retaliation. But many in Europe remain suspicious about America’s desire to unlock more money through financial engineering. On April 17th Christine Lagarde, president of the European Central Bank, suggested that such proposals face a “very serious legal obstacle”.

A drip of funds would be welcomed by Ukraine, but a big wodge of cash, as promised by America’s proposal, would be better still. European politicians would therefore be wise to sign up to it before there is a new occupant of the White House.

While I study international security for a living, the finer points of economic tradecraft are outside my expertise. In a just world, these assets would indeed be used to compensate Ukraine for damage inflicted in Russia’s illegal war and to help fund the war effort. It’s really the least the international community should do to punish Putin’s transgressions.

Clearly, though, an international system with state sovereignty at the core is going to make it very difficult to seize state assets. One would think siphoning off the interest would be easy enough but the more, the better.

Unfortunately, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe has about the same amount of strength as a chocolate teapot.

It’s a useful indicator of how the climate of opinion in European circles stands.

But this needs the support of actual governments to strong-arm their central banks, kicking and screaming, to do the deed.

At the very least, it needs buy in from US, UK, Japan, Germany, France, Italy and (here’s the fly in the ointment) Switzerland.

Just seize all Russian assets, and send Mad Vlad a nice thank you note.

I hope and pray they find a way. We must back Ukraine and Europe with every fiber, till the bitter end.