Productivity Killing American Economy?

Derek Thompson argues that "the real reason Americans fell so squeezed" is our obsession with productivity.

Atlantic business editor Derek Thompson argues that “the real reason Americans fell so squeezed” is our obsession with productivity.

Americans have a complicated relationship with productivity. We obsess about our personal efficiency, but we don’t think much about efficiency across broad swaths of the economy. Productivity is the not-so-secret sauce in our GDP. We’re the second-largest manufacturer in the world even though manufacturing jobs have shrunk to less than 10 percent of our economy. We’re the world’s third-largest agricultural nation even though only 2 percent of us farm. The reason we can do so much work with so little is that the U.S. economy is incredibly, and increasingly, efficient at making some things cheaply.

Don’t ask David Allen to explain this. Ask David Autor. He’s the MIT economist who, in last month’s cover story, “Can the Middle Class Be Saved?“, told Don Peck that technology and offshoring is replacing jobs for the middle-educated middle-class. “Almost one of every 12 white-collar jobs in sales, administrative support, and nonmanagerial office work vanished in the first two years of the recession,” Peck writes, and one in six blue-collar jobs disappeared in production, craft, repair, and machine operation.

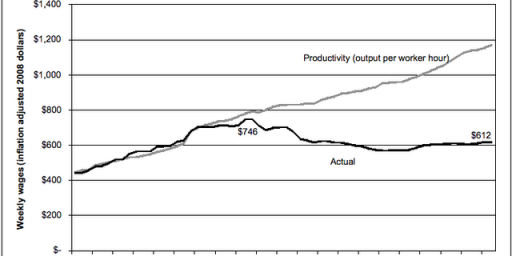

We know where the jobs are going — to machines, software, and foreign workers. We also know why they’re going away. Global competition gives companies the incentive to be more productive, and technology and foreign labor gives companies the means to be more productive. Automation lets one employee handle the work of three, or three hundred. Off-shoring lets ten Asian workers receive the salary of one. As these corporate Getting-Things-Done strategies make the typical worker increasingly expendable, real wages have stagnated, or declined, to their 1950s levels.

What’s so bad about 1950s wages, anyway? you may ask. They worked for the 1950s. We could make do with them today if the price of everything — from socks, to televisions, to medicine — moved at the same rate. But that is not what’s happened. Instead, socks got cheaper, televisions got more complex, and health insurance got much more expensive.

[…]

In fact, eating and clothing ourselves is getting easier all the time. Before the Great Depression, about 35% of family expenditures went to food and threads. Today, we spend only 10% of our income on food and 3% of our income on clothes. Again, this is an achievement of manufacturing and farming efficiency.

It doesn’t end there. Behind the most important technology stories of our time, there is a clear theme: The triumph of software. Consider the rise of Netflix over Blockbuster, music sharing over albums, Flickr over Kodak, Amazon over Borders, wireless Verizon over wired Verizon, webpages over printed pages. Everything getting cheaper feels the touch of innovation — especially online innovation, IT, and computer software.

But there’s a dark side behind the advance of productivity: Cheaper goods need cheaper workers.

[…]

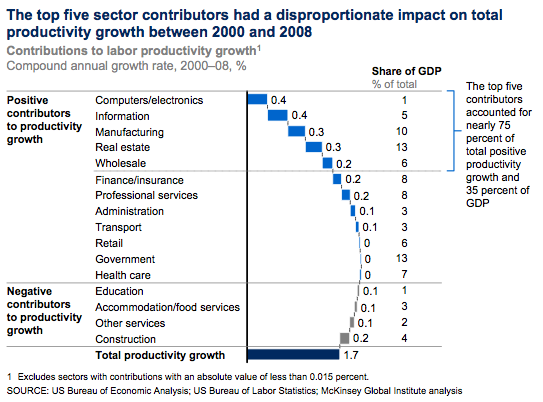

The reason why toasters are cheap and health insurance is not is that the productivity gains that made toasters — not to mention computers, media*, durable goods, food, and clothes — more affordable are not spilling over into health care. The next chart from McKinsey tells the story: More than half of total productivity growth comes from computers and information technology. Practically zero comes from health care and education. In fact, one reason why heath and education are adding the most jobs today is that employers can’t meet new demand with technology or offshoring. They have to keep hiring people.

I used to tell my students that, if a job held by an American could be done more efficiently by an illiterate Third World peasant, it ought to be. The thinking was that people in high skill countries should gravitate toward high skill jobs. Naturally, things that are high skill today won’t be tomorrow but that’s creative destruction and has been a boon to Western society–and the world at large–for more than two centuries.

It’s possible, though, that this bubble has burst. Thompson’s solution is the usual one: education. But not everyone has the ability to master complex mathematics and scientific concepts. And it’s quite possible that, even were that not a barrier, that there are simply not enough high skill jobs to go around.

No. Comparative advantage not absolute advantage.

Additionally, I think that something that’s being ignored is that the skill-level required for a particular job is itself subject to policy and design. 300 years ago weaving was done by skilled craftsmen, master weavers. We produce enormously more cloth at tremendously higher quality vastly less expensively than we did 300 years ago and the operators of the automated looms are less skilled than the master weavers were.

Why do we have artisanal medicine and higher education? Is it because it’s the only way to do it or is it because of the power of the guilds?

James,

“I used to tell my students that, if a job held by an American could be done more efficiently by an illiterate Third World peasant, it ought to be. The thinking was that people in high skill countries should gravitate toward high skill jobs.”

The problem isn’t that jobs which can be done by an illiterate third world peasant are being off-shored. It’s that jobs which can be done by an educated third world professional are being off-shored. When a radiologist in India will read x-rays or an accountant in Ecuador will audit the books for 1/10th what a similarly educated American professional would, education will not be a panacea.

@Dave Schuler and @Moosebreath: At the time, we were talking about things like NAFTA putting South Carolina garment workers out of business, since Mexicans could do routine tasks on sewing machines much more cheaply. It still strikes me as reasonable for that to happen.

It gets a lot more complicated, though, when just about ANY job can be outsourced and create a race to the bottom.

And this is the crux of the problem. We’re not able to outsource lawyers yet, but we have begun to outsource a lot of the mundane tasks done by junior associates, such as legal research and document review. Ditto doctors. And I’m sure we all know plenty of computer programmers whose jobs were outsourced to India. Education is no longer a panacea in the internet age when some well-educated person halfway across the globe can do your white collar job for a fraction of the price.

I’m not so sure we’re well served by outsourcing low-level jobs to other countries either, despite all the free-trade propaganda. What happens to us as a nation when we can no longer make a lot of the things on which we depend (such as computers) at home?

There were things that we missed, in that first free trade era, with talk of low skills jobs and 3rd world labor.

Broadly, what we missed was that it wasn’t a one-time deal. It wasn’t “siphon off 5% low skill jobs, shift our workforce, and be done.” We didn’t expect those “low skills nations” to “climb the skills ladder” and repeat the cycle again, and again.

We missed that if every exported job is a labor reduction, then that person reduced is likely to live on wealth, until that wealth is exhausted. That is either individual wealth through savings, or collective wealth, through social services.

We had a dream of retraining, and net-jobs elsewhere, but those were never more than vague assurances, by the economists, that “comparative advantages” all balance out, in a net net sense.

Should they? Why should an aging population, with high salary expectations, in a land with increasingly scarce natural resources, be net-even? Let alone a net-winner?

(Obviously every job lost to automation behaves the same way, causing every net-displaced worker to shift to savings, their or ours.)

Productivity is not a choice. The circuit boards in today’s electronic devices or the elctronic components on them cannot be constructed by people. A few engineers and technicians and engineers are required but they make as much product as hundreds of production workers. A worker can’t manufacture something he can’t see. I don’t know how you address this problem because it’s not about productivity as much as it’s about necessity.

@Ron Beasley:

Well yeah but, Taiwan has gained a lot of net-jobs based on those tiny transistors.

Several related themes in today’s Marketplace.

If you don’t have productivity increases, the labor price (amount of labor effort to obtain) of things purchased to live remain the same and there is a stagnation in job growth so new entrants must wait until one of the old workers leaves the workforce to achieve steady employment.

Have we achieved the maximum number of jobs permissible under our current regulatory environment. It certainly could be we have for trade-able jobs. The direct salary, regulatory mandated and compensation benefits, taxes and documentation have overcome the added cost of manufacturing and shipping overseas. If so, fewer workers will be supporting more and more of the population, which can only happen if the productivity of those workers keep increasing.

“We’re the second-largest manufacturer in the world even though manufacturing jobs have shrunk to less than 10 percent of our economy. We’re the world’s third-largest agricultural nation even though only 2 percent of us farm.”

These kind of statements are misleading in my opinion.

First because the way one should asses absolute size of a particular sector is mater to debate (http://shopfloor.org/2011/03/u-s-manufacturing-remains-worlds-largest/18756).

Second, and more importantly, because one should factor in the size of a nation’s population. And this is true also for GDP. We should be comparing relative sizes to countries such as Germany and Japan or even France. Not absolute sizes with countries such as China and India.

Nevertheless,I do find the term “productivity obsession” very a propos. It seems to mirror our obsession with volume over quality. Comparisons with western European countries would be interesting in many respects. If you consider farming for example, most European countries have topographical constraints we don’t have and agriculture has become as much about environment protection as food production. Are we really factoring in all the long term costs of our food industry? I am not sure.

@JKB:

This is a “be careful what you wish for thing.” Productivity is measured as output per worker. You can raise it be increasing output, but you can also raise it by reducing workers.

Consider a SciFi future, in which FedEx is able to increasingly replace package handlers, then drivers, then actual delivery staff, with robots. Even at static output, same package delivery rate, same prices, the “productivity” of the company steadily increases.

Net good? Well, if each displaced worker can find a better paying job, yes. If not, no.

BTW, in that Marketplace podcast above, they talk about the possibility of 9% unemployment “as a new normal.”

Let’s hope that is a moment of pessimism, darkest before the dawn, kind of thing … because if it is as bad as they suggest, with an employment recovery out at 2024 or something … that changes EVERYTHING.

A pattern has emerged, in these pages, and in my conversations with flesh and blood rightists.

It is that they claim regulations and benefits eject US jobs. That seems like innumeracy to me. Here’s why:

The labor wage in China is $1.50/hr.

The minimum wage in the US is around $8.00/hr. Let’d double that for benefits and etc., and call it $16.00/hr.

Sure, we can see why labor would move toward $1.50/hr rather than $16.00/hr.

But let’s say you wanted to “fix” that on the US side. How low would you actually go?

Are you really proposing $1.49/hr in the US?

Or are you making some vague implication that say $10.00/hr, or $8.00/hr, or even $6.00/hr beats China … because we’re Americans and we’re worth 4 or 5 or 6 times as much?

I have to say, I always bought in to the whole free trade (protectionism = trade war!, comparative advantage, etc) idea. Lately I’ve been questioning it. If the gains from free trade are concentrated at the tippy top and our society resists redistribution (and really, it’s better to have decent jobs for people than to redistribute via the government), the outcome appears to suck. Maybe we’re doing this wrong.

What is our comparative advantage, exactly? For a while there it looked like maybe it was Finance. Whoops!