Real Military Spending

An interesting analysis by The Economist.

The Economist‘s Graphic Detail department assesses “How countries rank by military spending.” Rather than using nominal spending or simple purchasing power parity, as has been done for years, it differentiates equipment cost and personnel spending.

To assess the state of international affairs, a good rule of thumb is to follow the flow of money or weapons. Defence budgets handily track both. A tally released by SIPRI, a think-tank based in Stockholm, suggests that governments are worried: 102 of the 173 countries included in the study increased their defence budgets last year. Globally, spending in real terms was up by 6.8% from 2022, the largest year-on-year increase since 2009.

Even this is useless without factoring in inflation rates.

Some of the biggest increases came from America’s NATO allies in Europe after a long period of low spending. Excluding America, nato members increased spending by $68bn, or 19%, between 2022 and 2023. Adding Finland and Sweden to the alliance has boosted NATO’s annual spending by a further $16bn.

But these figures are tricky to compare: the amount spent on wages and fuel, for example, will stretch a lot further in some countries than in others. To get around this, The Economist has adjusted SIPRI’s estimates for military purchasing-power parity (ppp), with help from Peter Robertson, a researcher at the University of Western Australia. This makes defence budgets comparable with America’s: pay is adjusted for wage differences and operating costs for general price levels. (Equipment costs are left the same, as much of the kit is imported, and its relative quality is hard to judge.)

Offhand, this strikes me as more useful than standard comparisons. There are pieces of the defense budget (salaries, most notably) where local cost of living very much matters and others (imported arms, for example) where it really doesn’t. So, while the US defense budget is massive, it’s not directly comparable to China’s and Russia’s because so much of our outlay is for pay, housing, retirement, healthcare, and the like in a much more expense economy. That doesn’t directly translate to combat power in the way that purchases of fighter jets and aircraft carriers do.

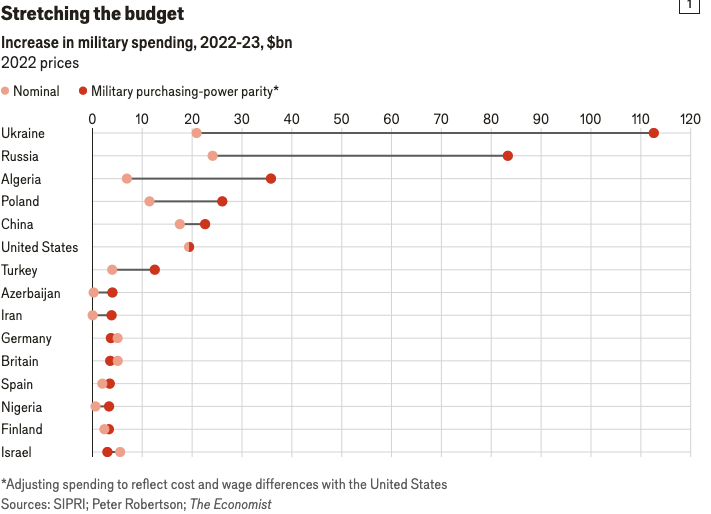

This is what that translates into in terms of year-on-year increases:

Therefore, they posit,

The adjustments show that Ukraine’s budget increases (though not its total budget) will stretch further than Russia’s, for example, even though its budget grew at a slightly slower rate in nominal terms (see chart 1). And money spent by America’s allies in NATO will matter much more than the dollar figures suggest. Their annual spending in 2023 was just 47.3% of America’s, but adjusted for their lower costs it was 78.5%.

Which makes sense: while the various weapons systems cost what they cost, it’s cheaper to care and feed for a Ukrainian soldier than an American or German soldier.

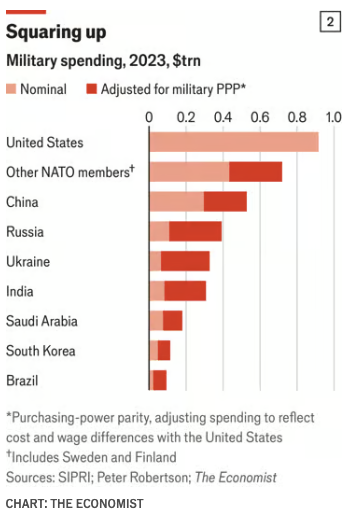

And here’s how overall spending compares with their adjustments factored in:

Since the US is the baseline, its nominal and adjusted figures are identical. But the gap in the rest of NATO’s contribution is significantly reduced by the adjustment. And, quite rightly, the nominal advantage over competitors China and Russia, while still huge, is radically reduced by adjusting for local cost of living.

The final ranking shows that America still spends far more on defence than any other country. In 2023 it spent $916bn on its armed forces (see chart 2). Taken together, its 31 allies in NATO come in second: they spend $434bn or $719bn adjusted for cost differences. The alliance’s armed forces are not unified, but it is still useful to compare its spending with others’. Russia and China, for example, respectively spent just 8% and 22% of the NATO total in 2023. When that spending is adjusted for military-PPP it is worth 24% and 32% of NATO’s outlay.

America’s allies still have further to go. Jens Stoltenberg, nato’s chief, recently said that just 18 members will meet the alliance’s target of spending at least 2% of GDP on defence this year (though that is up from 11 members in 2023).

The degree to which adding US and other NATO together as a comparison is quite mission-dependant. It’s certainly more useful vis-a-vis Russia than China.

Some of these figures need to be taken with a pinch of salt. Budget calculations are not consistent across all countries, and not all governments report accurately. (sipri relies on estimates rather than on official numbers for China, for example.) They also show running costs and investment, not how effective that spending is. But these budgets are nevertheless a good indicator of a country’s military trajectory: they shape what countries will be able to do, and suggest what they plan to do, in the years to come.

I’m actually reasonably confident in the US/NATO figures but, yes, numbers supplied by the Russian and Chinese regimes are likely distorted.

While interesting Economist’s analysis would be much more useful if it took force readiness into account. What we do know is that the force readiness of most of our NATO allies has been declining for decades. Some say that U. S. force readiness needs improvement. State the problem as one of those math textbook word problems:

“In 1960 it is estimated that you need to spend 2% of GDP per year on your military to maintain an adequate level of force readiness. You spend 1.5% of GDP for 60 years. What percentage of GDP do you need to spend for an adequate level of force readiness?”

The question is unanswerable without more information but the answer is: possibly much more than 2% of GDP. And then there’s the question that World War II raised: do we actually want the Germans to maintain a high level of force readiness?

Shorter: it’s complicated.

I read the Economist story, which is brief. The above quotes are nearly, if not entirely, the whole article. Despite a much smaller economy, Ukraine’s adjusted budget appears to be only like 10% lower than Russia’s. It’s unclear to me whether the Economist’s budget includes foreign assistance. In any case, win or settle, Ukraine’s going to come out with a huge debt.

@Dave Schuler: Yes, good point on readiness. It is, alas, likely not quantifiable and many of the NATO allies really haven’t deployed into combat at a significant level in decades.

Obviously there’s a lot more that goes into assessing military power. A well-trained pilot is better than a poorly-trained pilot. An experienced NCO is more effective than a recruit. And strategy and doctrine are hard to assess in dollar terms. There’s also geography – for example we have multiple warm-weather ports on both coasts as well as far-flung bases, Russia does not, and China is still trapped behind the first island chain. Then there’s the question of whether you’re playing offense or defense.

The consensus seems to be that our toys are better than their toys, and our soldiers better trained. But dramatic change is coming with drones and presumably AI. The Russian Navy was utterly dominant in the Black Sea, and now they’re hiding from Ukraine which doesn’t even have a navy. The horse was the greatest piece of military equipment for centuries, and then, all at once, it wasn’t. See also: battleships. And now, tanks.

This seems more right to me than most of the other comparisons out there.

It makes sense the US is still ahead considering the US has capabilities no other military has, has readiness levels no other military has, global power projection and presence that requires higher force levels, and maintains a kind of military equivalent of a public good for both the world and our allies – GPS plus lots of space and airborne intelligence and communication systems.

One key point to remember is that European military spending is plagued by horrendous inefficiencies.

Each country maintaining its separate systems for recruitment, training, procurement, payrolls, intelligence, planning, etc etc etc. Everything from marching bands upwards.

NATO provides only a limited amount of commonality; while the EU has no formal “directive function” in defence at all.

Consider how inefficient the US military capability would be if it were based on every states separate National Guard forces; and each jealous of its sovereign rights, and with the political imperatives relating to bases and procurement.

The answer may turn out to be a sort-of revival of the abortive European Defence Community of 1952. Leveraging such assets as the Galileo GPS system, Arianespace,

But that would almost certainly exclude the UK, which was highly sceptical of such projects even when an EU member.

And there is also the question of strategic stance and consequent force structure, composition and alliance relations.

For good reasons, the central/eastern states are focused on countering Russia, and believe that a in that the US is vital, and building a “European pillar” less so.

Italy and Spain are focused more on Med/North Africa; Greece and some others on Med/Middle East.

While both the UK and France, in their different ways, tend to be more “global” in both interests and outlook, and force posture.

Forging a coherent “European” defence policy out of these distinct national interests is a tricky exercise.

And there is also the bogeyman in the wardrobe, that’s seldom openly stated (except sometimes by the French): relations with US strategy and policy.

Spending on “out of area” capability to act as a mini-Me to the US has limited appeal to democratic politicians and military planners dealing with constrained resources.

It has had an often unhappy history, which Americans, understandably enough, often overlook.

But even the UK, perhaps the most strategically US-oriented European state (though Poland is close) has, un-ostentatiously (compared to France’s more open distancing) long had a global policy of limited liability re. supporting US strategic goals.

Though the extent of this has varied.

See Iraq and Afghanistan, of late and unpleasant memory.

Recently the UK has moved to more direct secondment in some respects re. distant waters naval/air policy.

eg AUKUS and mooted SSN force expansion and basing in Australia, the new aircraft carrier force, and the recent RN/RAF engagements in defence of Israel and in the Red Sea.

Looks like a better assessment than most. My general sense is that the state of readiness for China is not good. They have lots of poorly trained militia. Russia used its best troops at the start of the war so not a lot of good troops ready to go. Should also have a way to assess manufacturing capability for weapons.

Steve

@JohnSF:

I have long believed the French are right to push for a common European defense. If Trump wins and war with Russia breaks out we will not be there. I doubt very seriously whether Trump would honor any commitment to anyone that involved war – the spotlight would shift away from him, there’d be risk of public failure and he wouldn’t see a profit. It’s a bit late for Europe to get its act together, but they should press hard. If Trump wins and there’s trouble we will abandon you.

@Michael Reynolds:

Being a Brit, I tended to default to “whatever the French want, we don’t”

😉

Of late, I tend to think they may have had a point, dammit.

Macron is being rather clever recently, trying to woo the Poles, and the the Nordic/Baltic/Balkan states.

If he can get them to buy in, Germany may be driven to align due to internal politics.

Which has been the goal of Paris since 1956; harness German industrial capacity to French strategic vision.

The UK tended to act as a spoiler to that.

(The different “lessons of Suez”)

But Trump, and still more (being as Trump himself is just a fuckwit) the willingness of many Republicans to go Trumpian (actually not unforetold re. both “paleocons” and phony libertarians) has set off alarm bells in London and Berlin.

The current UK govt. is incapable of strategic reassessment re Europe, due to “stupid Tory”.

Though, tbf, it has calculated sensibly re. AUKUS and missile defence of Israel.

Note the “dog that did not bark”: Starmer has said nowt re. RAF/RN actions in this or re. Houthis in Red Sea.

I suspect Privy Council discussions have (not) taken place. 😉

(Because Privy Council discussions never DO take place. That’s how it works.)