Rwanda’s Lessons Yet to be Learned

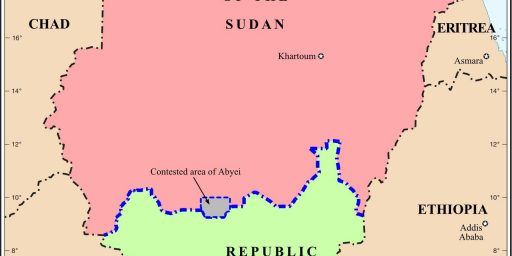

Don Cheadle and John Prendergast have a stirring piece in today’s Boston Globe entilted, “Rwanda’s lessons yet to be learned.” Sparked by the forthcoming film, “Hotel Rwanda,” they plea for international intervention in Sudan and Congo.

The failure to act forcefully in Sudan and Congo highlights how little progress the world has made since the events of 1994. These debacles also remind us that the world body chargged with leading the response to crises of this kind — the United Nations Security Council — remains unwilling or unable to confront the perpetrators of mass atrocities in the world’s peripheral zones. Divisions within the Security Council over whether to act remain huge, and the divisions themselves become an excuse for inaction. The main difference, however, between 1994 and today is that we still have time to act to help save lives in Congo and Sudan. Millions of lives. The death tolls have mounted in slow motion in Congo and Sudan compared to Rwanda, where 800,000 were killed in a hundred days, the fastest rate of killing in recorded history. It is not too late to act.

Let’s go back to the lessons of the Rwandan genocide. It was perpetrated with ease by the Rwandan government and its militias because there was no accountability for the killing and no protection for the targets. These two ingredients — accountability and protection — are precisely what are missing from today’s response in Congo and Sudan.

First, accountability. The message needs to be sent to the perpetrators and orchestrators of the killing that the days of impunity are over. That can be accomplished through a number of tools: international prosecution for war crimes, arms embargos, travel bans, and asset freezes, all focused on those that are most responsible.

Second, protection. When a government abdicates its responsibility to protect its own citizens, then all international efforts must go toward protecting those people. In both Sudan and Congo, international forces have been deployed to observe tenuous cease-fires. But the real problem is predatory militias (like the Sudan government-backed Janjaweed, or “devils on horseback”) that prey upon civilians and carry out the political objectives of their patrons in nearby capitals.

While intervening to protect the innocents in Sudan and Congo would be infinitely just, the reasons that we haven’t “learned” the “lessons” of Rwanda is that it’s just not that easy. The history of foreign intervention in civil wars is long. The list of successes is short indeed. The United States and others should be willing to help out financially. Expending the blood of our soldiers in what is likely to be a futile effort, however, is not something to be undertaken likely.

As harsh as it may be, the fact of the matter is that the genocides in those countries has virtually zero impact on the security of the West. The mass killings are tragic but home grown. Unlike the tsunamis that have devastated the Indian Ocean region, they are man made. The responsibility of the West to intervene is limited, at best.

I think that one of the problems here is that there’s no national consensus on the use of the level of force that would actually be required to accomplish something material. Oddly, we can get general agreeement to use a level of force that’s practically useless.

But for good or ill we’ve tended to restrict our use of substantial force to situations in which we have a national interest narrowly understood.

i disagree. we should WHACK the badguys HARD with whatever we CAN! Cruise missiles would be fine – we DON’T have to invade or occupy or even send troops. BOMB THE BAD GUYS! For a week or so. From an aircraft carrier and sub and with one or two b52’s from DG.

It would send a good message:

“commit genocide you die!”

There is NO DOWNSIDE TO THIS.

Except that by whacking those bad guys all the time, we expend weapons we might need to whack bad guys who do affect our national security.

Of course, I’d trade the Departments of Commerce, Education, Energy, and Labor for enough budget to buy weapons to whack everybody else, but I don’t think any compassionate legislators would vote for that.

The only countries with the military resources to ever intervene effectively are US, UK, Australia and France. It is just not possible for these countries to solve every civil war in Africa. We would have troops on the ground all the time. Plus, only those countries on the coasts are good choices. Do we want US forces in the interior of Africa constantly? I am sorry to say that this is just hopeless liberal idealism.

Hmmm yes, we ony have a “responsibility” to intervene in countries that sit atop on ocean of oil.

good points Brian J.

But all we have to do is bomb a few of the tyrannical genocidal despots – and their villas – to get their attention.

so it won’t cost us a lot.

and: it’s a whole lot more effective than sending them carefylly worded warnings fromm the UNSC.

bottom-line: it’s more compassionate to whack bad guys committing genocide than to sit on your asses in turtle bay hand-wringing/hand-writing and hand-jiving while hundreds of thousands of people get murdered!

SAVE THE CHILDREN – KILL TYRANTS!

Quick — name the tyrant you would bomb in the Sudan that would make everything better. Top 5? James may be wrong about whether we should intercede, but he’s right that it’s not that easy.

While I agree we are not prepared to get involved in Africa, I reject the Chomsky approach that Africa must take care of Africa, that is a statement of historical romanticism, what we need is more imagination and forward thinking, on one hand, we have future trade to consider (to complete for Africa from China and Europe) and on the other hand, we can not let violence spawn, that is exactly how the Taliban came into being.