Scott Carpenter, Second American To Orbit Earth, Dead At 88

Scott Carpenter, one of the original group of American Astronauts known as the “Mercury 7” and the second American to orbit the Earth, has died at the age of 88:

M. Scott Carpenter, whose flight into space in 1962 as the second American to orbit the Earth was marred by technical problems and ended with the nation waiting anxiously to see if he had survived a landing far from the target site, died on Thursday in Denver. He was 88 and one of the last two surviving astronauts of America’s original space program, Project Mercury.

His wife, Patty Carpenter, announced the death. No cause was given. Mr. Carpenter had entered hospice care recently after having a stroke.

His death leaves John H. Glenn Jr., who flew the first orbital mission on Feb. 20, 1962, and later became a United States senator from Ohio, as the last survivor of the Mercury 7.

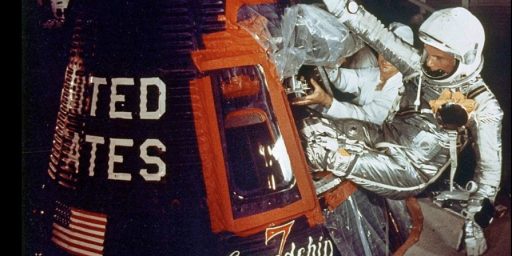

When Lieutenant Commander Carpenter splashed down off Puerto Rico in his Aurora 7 capsule on May 24, 1962, after a harrowing mission, he had fulfilled a dream.

“I volunteered for a number of reasons,” he wrote in “We Seven,” a book of reflections by the original astronauts published in 1962. “One of these, quite frankly, was that I thought this was a chance for immortality. Pioneering in space was something I would willingly give my life for.”

For 39 minutes after his capsule hit the Caribbean, according to NASA, there were fears that he had, in fact, perished. He was 250 nautical miles from his intended landing point after making three orbits in a nearly five-hour flight. Although radar and radio signals indicated that his capsule had survived re-entry, it was not immediately clear that he was safe.

A Navy search plane finally spotted him in a bright orange life raft. He remained in it for three hours, accompanied by two frogmen dropped to assist him, before he was picked up by a helicopter and taken to the aircraft carrier Intrepid.

The uncertainty over his fate was only one problem with the flight. The equipment controlling the capsule’s attitude (the way it was pointed) had gone awry; moreover, he fired his re-entry rockets three seconds late, and they did not carry the anticipated thrust. He also fell behind on his many tasks during the flight’s final moments, and his fuel ran low when he inadvertently left two control systems on at the same time.

Some NASA officials found fault with his performance.

“He was completely ignoring our request to check his instruments,” Christopher Kraft, the flight director, wrote in his memoir “Flight: My Life in Mission Control” (2001). “I swore an oath that Scott Carpenter would never again fly in space. He didn’t.”

Mr. Carpenter was the fourth American astronaut in space. Alan B. Shepard Jr. and Virgil I. Grissom flew the first two Mercury flights, and then Mr. Glenn orbited the Earth. Mr. Carpenter was the fourth man to go into orbit. Two Russians in addition to Mr. Glenn had preceded him.

(…)

His mission called for greater pilot involvement than Mr. Glenn’s. With photographic tasks to perform and science experiments to oversee, he seemed to be having a grand time, though the cabin became uncomfortably warm. But serious trouble arose when the equipment controlling the way the capsule was facing malfunctioned, requiring him to determine the capsule’s proper attitude visually.

“The last 30 minutes of the flight, in retrospect, were a dicey time,” he recalled in his memoir, “For Spacious Skies” (2002), written with his daughter Kris Stoever. “At the time, I didn’t see it that way. First, I was trained to avoid any intellectual comprehension of disaster — dwelling on a potential danger, or imagining what might happen. I was also too busy with the tasks at hand.”

Splashing down 250 nautical miles from the nearest recovery ship, he got out of his capsule through a top hatch, then inflated his raft and waited to be picked up.

Finally the voice of mission control, Shorty Powers, announced, “An aircraft in the landing area has sighted the capsule and a life raft with a gentleman by the name of Carpenter riding in it.”

President Kennedy greeted Commander Carpenter and his family at the White House in June 1962 after the Carpenters had been hailed at parades in Denver and Boulder and honored at City Hall in New York. A few days after Mr. Carpenter’s mission, the University of Colorado gave him a long-delayed degree in aeronautical engineering at its commencement, citing his “unique experience with heat transfer during his re-entry.” He had missed out on his degree by not completing a course in heat transfer as a senior in 1949.

But the issue of the flight’s brush with disaster lingered. A NASA inquiry determined that because of a 25-degree error in the capsule’s alignment, the retro rockets had fired at an angle that caused a shallower than normal descent. That accounted for 175 miles of the overshoot, with the remaining 75 miles caused by the late firing of the rockets and their failure to provide the expected thrust.

Mr. Kraft, the flight director, had been angry that Mr. Slayton was denied the mission because of his heart problem, and he was furious at Commander Carpenter, feeling that he had not paid sufficient attention to instructions from the ground.

Commander Carpenter’s prospect of obtaining another NASA mission was ended by a motorbike injury that led to his leaving NASA in 1967.

In a 2001 letter to The New York Times in response to a review of Mr. Kraft’s book, Mr. Carpenter wrote that “the system failures I encountered during the flight would have resulted in loss of the capsule and total mission failure had a man not been aboard.”

“My postflight debriefings and reports,” he added, “led, in turn, to important changes in capsule design and flight plans.”

In his book “The Right Stuff” (1979), which told how the original astronauts reflected the coolness-under-pressure ethos of the test pilot, Tom Wolfe wrote that Mr. Kraft’s criticism fueled NASA engineers’ simmering resentment of the astronauts’ status as pop-culture heroes. The way Mr. Wolfe saw it, word spread within NASA that Mr. Carpenter had panicked, the worst sin imaginable in what Mr. Wolfe called the brotherhood of the right stuff.

Mr. Wolfe rejected that notion. “One might argue that Carpenter had mishandled the re-entry, but to accuse him of panic made no sense in light of the telemetered data concerning his heart rate and his respiratory rate,” he wrote.

“The Right Stuff” was made into a movie in 1983, with Charles Frank as Mr. Carpenter.

Mr. Carpenter also carved a legacy as a pioneer in the ocean’s depths. He was the only astronaut to become an aquanaut, spending a month living and working on the ocean floor, at a depth of 205 feet, in the Sealab project off San Diego in the summer of 1965. When he returned to NASA, he helped develop underwater training to prepare for spacewalks. He returned to the Sealab program, but a thigh injury resulting from his diving work kept him from exploring the ocean floor again.

He retired from the Navy in 1969 with the rank of commander, pursued oceanographic and environmental activities and wrote two novels involving underwater adventures

Before his own mission, Carpenter was the person who delivered the historic sendoff “Godspeed John Glenn” as Glenn went off on his own history making mission into orbit. As noted, though, with Carpenter gone Glenn, now 92, is the last of America’s great first class of space pioneers left.

Sad to hear this just over a year after Neil Armstrong’s death. Very few of these guys left.

It’s a shame America no longer even has a way to get a person into space at all.

@Mikey: It’s a shame America no longer even has a way to get a person into space at all.

@BIll: That’s why I said “a person.” We launch plenty of satellites and there are a couple really cool things driving around on Mars, including one that is coming up on 10 years of operation. But no way to get people out of the atmosphere.

I think it should be assumed a capability to launch a person would include their actual, you know, survival.

The commercial crew program should resolve that problem, the target date is 2017. Work is proceeding on the SLS/Orion system, but it is badly underfunded (not surprisingly, due to Republicans in congress) NASA is chomping at the bit to get back into manned deep space missions, but at current funding levels, even if we get there we will probably not accomplish a lot.

Twenty years or so from now, American kids will watch the first people land on Mars. They will be from China. Our grandkids will be wondering what it’s like to live in a country that can accomplish such a remarkable feat.

@anjin-san:

Yes, and that’s fantastic. But I fear we’ve lost the vision. I know it’s expensive, I know we have big concerns in other areas, but I’m old enough to remember the kind of national unity we had when we were putting men on the Moon. Seems like we could use some of that about now, some unity unrelated to blowing other countries up, you know?

I’m still pretty pleased with the unmanned stuff we’re doing, though. That’s been pretty amazing the last few years.

My fear as well.

Depends on how you look at it. If you added up the entire NASA budget it’s 50+ year history, it would not equal a single year of DOD spending. The same people in Congress who had no trouble voting for the trillion dollar plus Iraq debacle are literally balking about spending a few billion more to help ensure the future of the human race. Polling shows that the public is badly misinformed about the actual cost of NASA.

http://blogs.discovermagazine.com/badastronomy/2007/11/21/nasas-budget-as-far-as-americans-think/

@anjin-san: I recall seeing the Apollo program cost about $150 billion total (in today’s dollars) over its entire duration. That’s not insignificant, although I think the lower cost of advanced technology today would allow us to return to the Moon for much less. And it would be spread out over several years.

Imagine if we’d put an extra trillion dollars into NASA over the last 10 years. We’d have colonies on the Moon.

(I just tried going to the NASA website to look up their budget…but due to the “shutdown” it’s not available…fortunately Wikipedia is still open.)

NASA’s budget for 2013 is around $17 billion. They get a lot done for that.