The Non-Competitive House

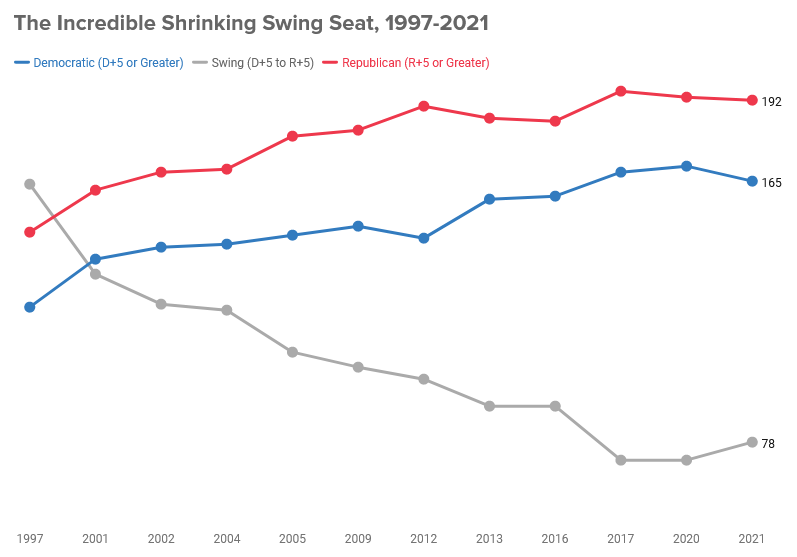

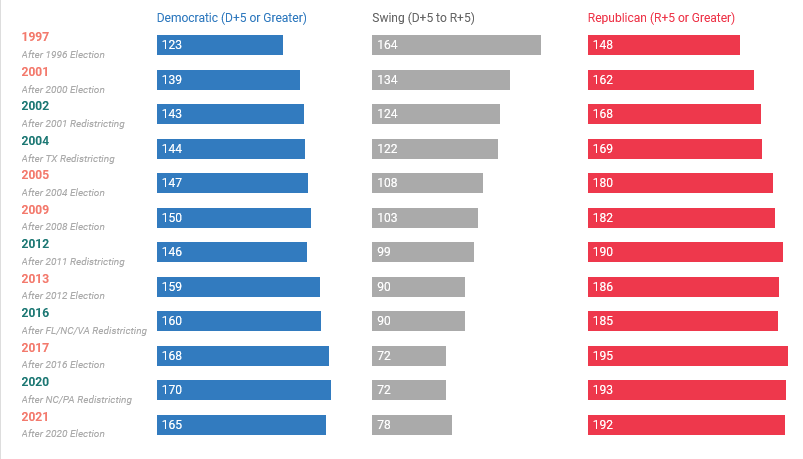

A recent report shows 78 of 435 seats in the US House are truly competitive.

The 2021 Cook Political Report Partisan Voter Index has been released. It is full of interesting data, but these graphs illustrate a theme I often discuss (two, actually):

We see here first that the number of House seats that are truly competitive is quite small (even if there was a slight rebound in the 2021 report of +5). Most of the seats in the US House of Representatives are settled in the primaries, not during the general election. This illustrated how little things like national popular opinion matter for political outcomes. To get re-elected to the House in most districts means appealing to the primary electorate, which is but a small slice of the citizenry. This is not a good way to generate representative Representatives (not that single-seat districts can ever do that anyway).

A second theme is that the Republicans have a built-in advantage of 27 seats (down slightly over the last two cycles).

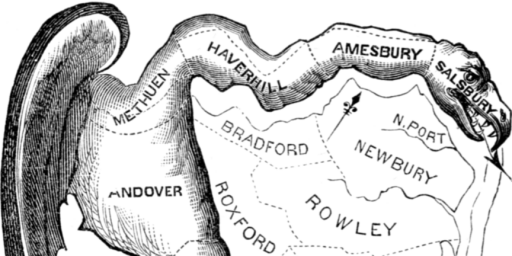

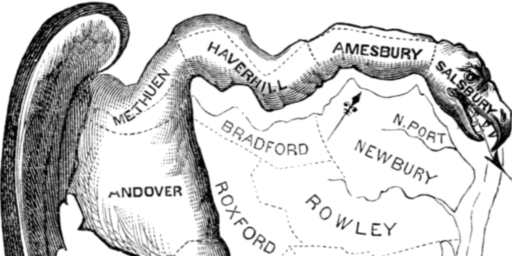

And it should be noted that gerrymandering is not the main problem, and HR1 is not going to fix this. The main culprit is geographical sorting.

The Cook PVI illustrates how voters’ natural geographical sorting from election to election, much more than redistricting and gerrymandering, has driven the polarization of districts over the last two decades. Our 12 unique sets of PVI scores over the past 25 years give us a powerful tool to isolate and quantify the impacts of sorting and redistricting on the makeup of House districts.

[…]

On balance, redistricting wasn’t as much of a factor in the House’s polarization as the most vocal opponents of gerrymandering might think. Of the net 86 “swing seats” that have vanished since 1997, 81 percent of the decline has resulted from areas trending redder or bluer from election to election, while only 19 percent of the decline has resulted from changes to district boundaries.

As I often note: single-seat districts do a really poor job of producing electoral results that truly represent the myriad interests of a given district (which is made worse by the need of politicians to win primaries). Further, the House is too small, which exacerbates the problem, especially since high-density urban areas tend to be heavily Democratic in orientation.

That trend line for swing seats should chill the blood of any fan of a government responsive to the consent of the governed. Sadly, since this represents the current conditions, the governed will have next to nothing to say about improving the trend. Our governmental dysfunction is self-perpetuating.

We’ve established that amending the Constitution is impossible, so perhaps we could change the Preamble to more accurately reflect 21st century US democracy:

“We the People of the United States, in Order give up on a more perfect Union, avoid Justice, insure domestic Hopelessness, provide for an uncommon defense, ignore the general Welfare, and obscure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do accept this Constitution for the United States of America as a death pact.”

Also an explanation as to why congress critters are more performative and less legislative that in the past.

Serious question, Steven: from your position as a professor of political science and long-time analyst of America’s political system, have you come to believe American politics is irrevocably broken?

Because from my position as a layman who is also a long-time observer of that system, I am beginning to think it is.

@Sleeping Dog: Yup.

@Mikey: It is definitely broken. I vacillate on whether it is irretrievably broken or not. I can see fixes, large and small, that would lead us in the right direction, but will confess to bouts of despair as to whether even the simplest fix will be instituted without a major crisis.

I’m learning a lot from this series of posts. Thank you.

In order to round out my understanding, I’m curious to hear the best argument for the other side. That is, what is the best argument for the position that these changes (and/or the current state) are an improvement? Or if not an improvement, then not as bad as you present it?

I’d love to hear your thoughts on this. I’m also open to being pointed in the right direction of a best representative for the other side. Thanks in advance.

@Mimai: Do you mean what is the best argument for the changes reflected in the charts?

@Steven L. Taylor:

I’m probably still a bit too naïve on this topic to articulate exactly what I want. That is, whether I want an argument in favor of the more specific vs. the more general issue. Perhaps one of these (though feel free to answer the question you think would do me most good….treat me like a curious but green student).

1) What is the best argument that the changes reflected in the charts are good/neutral/not-so-bad?

2) More generally, what is the best argument that “unrepresentative representation” is good/neutral/not-so-bad? (Or maybe “unrepresentative” steals a base for your position and thus needs to be softened for a true steelman argument)

It’s definitely depressing.

I wonder how redistricting will shake this up. I’m guessing not much.

@Andy: I expect it will make it somewhat worse.

The solution would appear to be to expand the House. We used to regularly expand the House of Representatives precisely to keep it, you know, representative. But we have not expanded it in over a century. In that time, each district has gone from representing about 200k people to about 700k people. Doubling the number of reps would eliminate almost all single-seat states, shift a bit of power to cities and divide up suburbs to be less of a hegemony.

When you consider both the small number of competitive seats and the absurdly large size of House districts observed by Hal_10000 above, it highlights the need to expand the number of seats in the House.

In theory it wouldn’t even require a constitutional amendment. In practice it might since present House members are unlikely to want competitive or smaller districts.

@Hal_10000:

It would not be the solution, but it would improve the situation. The only solution is to move to one of several options with multi-seat districts with some version of proportional representation. I cannot stress enough that the baseline problem is the use of single-seat districts itself.

@Dave Schuler:

The size of the House is set by statute, so no need to amend the constitution to expand.

IMO, the problem with expanding the House, is you’re asking its members to dilute their own power.

And that is one of the big obstacles that get in the way of reform and other necessary fixes. All such changes, no matter how good, invariably require some people to lose something, usually power. You can see this throughout history, and that’s why there’s a great deal of admiration for people like Cincinnatus and George Washington, who voluntarily gave up power they could easily have kept.

@Kathy: Without any doubt, reform is difficult in any context because it will dilute the power of those who have to do the reforming.

Reform tends to occur in the face of serious crisis or when a group thinks that reform is the only way to forestall a pending loss of power.

So, Dems have some level of motivation to engage in some level of reform when they are in the majority because the system is clearly stacked against them. But since they also fear changes having other consequences, they balk.

Late to the conversation, again. This is a cartogram showing the 2020 House election results with each district resized to about the same size (as all House districts have about the same population). Standard red/blue coloring*. I assert that to a first approximation, “Democrats represent urban and high-density suburbs, Republicans represent lower-density suburbs and rural areas” is reasonable. As a counterpoint to Dr. Taylor’s position about many people not being represented due to single-member districts, I would argue that this suggests the people elected would change relatively little if each state elected their representatives at large.

On a separate “what difference would it make” tack, legislation in the House is authored by the most senior members (who chair the committees), and what reaches the floor is controlled entirely by the Speaker. I don’t see larger multi-member dynamics changing that either.

* Lots of distortion in this cartogram. State outlines in yellow to help with that some. We moved last year, which took up too much time and energy, so I simply don’t recall if Pennsylvania reflects the districts as drawn after their state supreme court’s decision on gerrymandering or not.

@Michael Cain:

It is extremely important to note that I am not advocating at-large election. I am advocating proportional representation in multi-seat districts. This is not the same thing.

@Steven L. Taylor: Not to mention that multi-seat PR would lead to a breakup of the two-party duopoly.