Justices Divided on Partisan Gerrymandering

Oral argument hints that we may have a 5-4 ruling allowing state legislatures to continue stacking the deck.

AP (“High court seems wary of involving judges in redistricting“):

The Supreme Court’s conservative majority seemed wary Tuesday of getting federal judges involved in determining when electoral district maps are too partisan.

In more than two hours of arguments over Republican-drawn congressional districts in North Carolina and a single congressional district drawn to benefit Democrats in Maryland, the justices on the right side of the court asked repeatedly whether unelected judges should police the partisan actions of elected officials.

“Why should we wade into this?” Justice Neil Gorusch asked.

Gorsuch and Justice Brett Kavanaugh pointed out that voters in some states and state courts in others are imposing limits on how far politicians can go in designing districts that maximize one party’s advantage. In light of activity at the state level, Kavanaugh asked if the country had reached the point where “this court and this court alone” must act.

But there was no certainty that the justices would, in the end, shut courthouse doors to claims over excessive partisan gerrymandering, as the practice of designing districts for political gain is known.

Kavanaugh, in particular, said he would not dispute the “problems of extreme partisan gerrymandering.”

The cases at the high court mark the second time in consecutive terms that the justices are trying to determine if they can set limits on partisan map-making. The court also could rule that federal judges should not oversee disputes over districts designed to benefit one political party.

Democrats and Republicans eagerly await the outcome of cases from Maryland and North Carolina because a new round of redistricting will follow the 2020 census, and the decision could help shape the makeup of Congress and state legislatures over the next decade.

Last year, the court essentially punted on cases from Wisconsin and the same Maryland congressional district that was before the court Tuesday.

Partisan gerrymandering is almost as old as the United States. While the court ruled 30 years ago that courts could police overly partisan map-making, the justices have never struck down districts on the ground that they violated the rights of voters from the minority party.

Supporters of limits on partisan redistricting say that it’s more urgent than ever for the court to intervene because partisan maps deepen stark political division in the United States and sophisticated computer programs allow map-makers to target voters on a house-by-house basis.

[…]

Complaints about partisan gerrymandering almost always arise when one party controls the redistricting process and has the ability to maximize the seats it holds in a state legislature or its state’s congressional delegation.

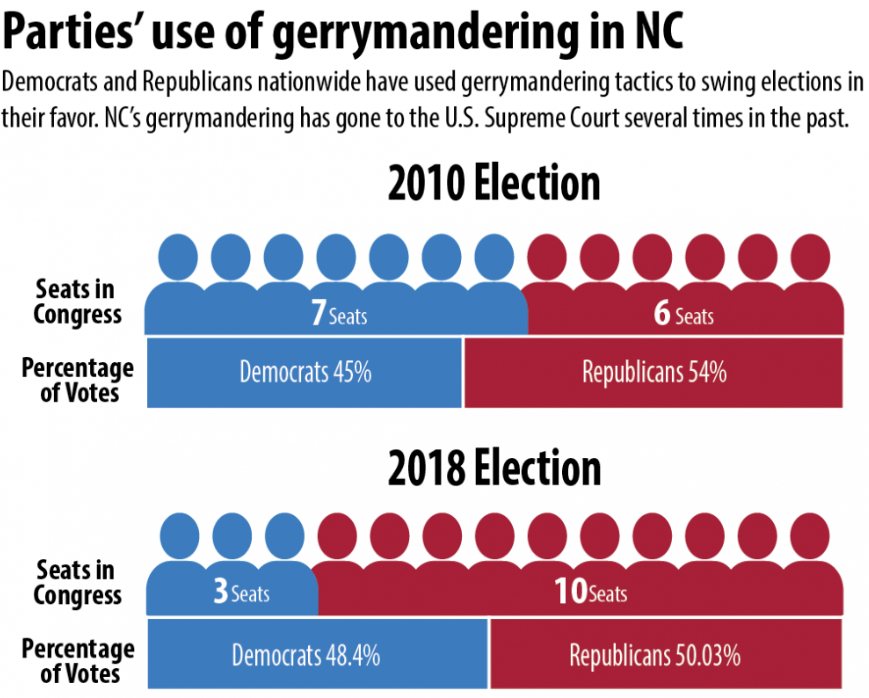

That’s what happened in North Carolina, where Democrats hold only three of 13 congressional districts in a state that tends to have closely decided statewide elections.

Republicans drew congressional districts that packed Democratic voters into the three districts that translated into landslide victories. Meanwhile, the map produced smaller winning margins for Republican candidates, but in more districts.

In Maryland, Democrats who controlled redistricting in 2011 wanted to increase their 6-2 edge in congressional seats. So they drew a map that would flip to Democrats a western Maryland district where a Republican incumbent served for 20 years.

Lower courts in both states struck down the districts as unconstitutionally partisan.

And the governors of both states also are urging the Supreme Court to “end gerrymandering once and for all.”

AFP (“US Supreme Court divided over gerrymandering case“):

The US Supreme Court appeared sharply divided on Tuesday as it heard a politically charged case about gerrymandering, the dark art of drawing electoral maps to extract partisan advantage.

The nine justices of the nation’s top court seemed split along ideological lines as they heard arguments in a case that could reshape the future of American politics.

The five conservative justices appeared inclined to let the states continue to work out solutions to the vexed question, which has sparked calls for reform from public figures including action star and erstwhile politician Arnold Schwarzenegger.

[…]

In the North Carolina case, the Republican authors of the 2016 congressional map explicitly stated their intentions.

– ‘People are bragging’ –

“I propose that we draw the maps to give a partisan advantage to 10 Republicans and three Democrats,” said a member of the redistricting committee, “because I do not believe it’s possible to draw a map with 11 Republicans and two Democrats.”

The plan was successful: in the 2018 congressional vote, Democrats won a majority of votes statewide, but only three of the 13 districts.

The Maryland case hinges on one rural district which remained in the hands of the same Republican for 20 years. It underwent a redistricting exercise in 2012, which added more urban voters, and flipped to the Democrats two years later.

Elena Kagan, one of the four liberal justices, said it appeared wrong for the court to “leave all this to professional politicians” who “have an interest in districting according to their own partisan interests.”

“People are bragging,” Kagan said, “because they think it’s perfectly legal to do so.”

Another liberal justice, Stephen Breyer, said he feared the amount of gerrymandering would only get worse over time.

“Politicians consider politics, yes,” Breyer said. “Our problem is ‘When is it too much?'”

Amy Howe offers an excellent summary of the argument on SCOTUSBlog. Some key points not covered in the news reports:

In 2004, the Supreme Court was sharply divided in a partisan-gerrymandering challenge to Pennsylvania’s redistricting plan. Citing a lack of a workable standard to determine when party politics crosses a line and plays too influential a role in redistricting, the court’s four more conservative justices at the time believed that courts should never have a role in reviewing claims of partisan gerrymandering. Four of the court’s more liberal justices argued that courts should police partisan-gerrymandering claims, while Justice Anthony Kennedy – who has since retired – staked out a middle ground: He argued that the Supreme Court should not review the Pennsylvania case, but he left open the possibility that courts could review partisan-gerrymandering claims in the future if a manageable standard could be established.

[…]

Arguing for the Republican legislators this morning, former U.S. solicitor general Paul Clement urged the justices to stay out of the fray. The Constitution gives responsibility for drawing congressional districts to the political branches, he emphasized: first to state legislatures, and then to Congress itself, acting as a supervisor. There is no role for the courts, particularly because plaintiffs in partisan-gerrymandering cases have repeatedly failed to identify a workable standard for courts to use in reviewing such claims.

Justice Neil Gorsuch seemed to agree that the problem of partisan gerrymandering is one that should be left for the political branches of government to deal with. He recalled that, in the court’s previous partisan-gerrymandering arguments, lawyers for the challengers had argued that the courts are the only institution that can remedy partisan gerrymandering. But, he posited, states have in fact taken action to address the problem. Why should we wade into this, Gorsuch asked Emmet Bondurant, who argued on behalf of one group of challengers in the North Carolina case, when that alternative exists?

Justice Brett Kavanaugh echoed this concern. He told Allison Riggs, who argued for a second group of challengers in the North Carolina case, that he understood “some of your argument to be that extreme partisan gerrymandering is a problem for democracy.” Referring to activity in the states and in Congress to combat partisan gerrymandering, Kavanaugh asked whether we have reached a moment when the other actors can do it.

Riggs responded that North Carolina, at least, is not at that moment. When Kavanaugh responded, “I’m thinking more nationally,” Riggs shot back that “other options don’t relieve this Court of its duty to vindicate constitutional rights.”

Chief Justice John Roberts also seemed to suggest at one point that the political process could take care of partisan gerrymandering. Partisan identification, he told Bondurant, is not the only thing on which people base their votes. A vote may hinge on a specific candidate, or who is at the top of a ticket, Roberts observed. When Bondurant pushed back with references to findings by social science experts, Roberts countered that “a lot of predictions turn out to be wrong.” In the 2018 election, for example, a “lot of things that were never supposed to happen, happened.”

Justice Stephen Breyer searched out loud for a formula that would capture what he characterized as the “real outliers.” He proposed a standard that would bar challenges to districting maps created by independent redistricting commissions, but that would deem a map an unconstitutional partisan gerrymander if a party wins a majority of the statewide vote but the other party wins more than two-thirds of the available seats.

Clement was unenthusiastic, telling Breyer that there is “so much in that that I disagree with.” Citing now-retired Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, Clement referred to any problems created by partisan gerrymandering as “largely self-healing.” By contrast, he warned darkly, if the Supreme Court were to rule that courts can review partisan-gerrymandering claims, partisan-gerrymandering cases will come to the Supreme Court – which will have to review them, because redistricting cases are among the narrow set of cases with an automatic right of appeal to the Supreme Court – “in large numbers.” “And once you get into the political thicket,” Clement continued, “you will tarnish the reputation of this Court for the other cases where it needs that reputation for independence.”

Riggs offered a similar appeal, although with a very different perspective, toward the end of her argument. She stressed that, “with all due respect, Justice O’Connor was not correct. This isn’t self-correcting.” And although “the reputation of the Court as an independent check is an important consideration,” “the reputational risk to the Court of doing something is much, much less than the reputational risk of doing nothing, which will be read as a green light for this kind of discriminatory rhetoric and manipulation in redistricting from here on out.”

This is yet another case where we are hamstrung by a Constitution negotiated in 1787, when very different conditions obtained. That document makes it crystal clear that state legislatures have plenary power to allocate their House seats as they wish. And the Supreme Court has thus far weighed in only to balance that power against other explicit Constitutional protections. Most notably, they have prohibited the use of race as a criteria in making districting decisions, reasonably arguing that doing so violates the 14th Amendment. And, going back to Baker v Carr in 1962, the Court has required that districts within a state be roughly equal in population, pursuant to the Equal Protection Clause.

Until now, they have always treated purely political considerations as within the province of the legislature. That accords with the plain meaning of the Constitution. But Kagan and Breyer are right: politicians have many more tools at their disposal to effectively control the outcome of elections than they did even a generation ago. Even Kavanaugh recognizes that we’ve perhaps gone too far.

Roberts’ line of questioning, suggesting that party affiliation isn’t the only thing upon which voters base their choice, seems rather odd. While it’s technically true, Bondurant is correct that it’s an incredibly good predictor. And, rather clearly, legislators in North Carolina and Maryland think drawing lines using indicators of partisanship is a worthwhile endeavor.

Regardless, my instincts nonetheless reside with the conservatives here. The Constitution is on the side of the state legislatures. So long as they’re not violating some other provision of the Constitution—and nobody seems to be arguing here that they are—then they have every right to game the system. That it’s awful public policy to do so is not a decision within SCOTUS’ purview.

Of course the Justice Boof Court is going to validate Republican policy. The merits of the case mean bubkis.

And so it will be for the next couple decades, at least.

Except we’re not, as that negotiation was radically changed by the 14th ammendment, even though conservatives like to pretend it never happened.

If the 14th ammendment curtails redistricting based on race, why doesn’t it also curtail redistricting on a broader equal protection basis?

Dr. Joyner –

At what point do people start feeling as though the minority is getting to rule over the majority? Because that’s the path we’re heading towards. As the GOP’s share of votes continues to plummet, they keep changing the rules to keep themselves in power.

Today I read an article where Trump’s team feels he can win the Electoral College in 2020 with 45% of the popular vote. If the GOP suppresses enough votes in Wisconsin, Michigan and Florida, it would easily happen. Assuming the Dem candidate gets over 50%, with the other smaller parties getting the other 4%, how do you think the 50%+ are going to feel about the system?

That’s where we are heading. In my opinion, you’re wrong about this. You can’t have fair elections if the starting point isn’t fair. And you can’t have legitimacy, either.

“At what point do people start feeling as though the minority is getting to rule over the majority? Because that’s the path we’re heading towards.”

That is not the path we are on, we are already there.

@Stormy Dragon:

The 14th Amendment is the only reason SCOTUS has any jurisdiction at all in what would otherwise be a state matter, so it’s not like we’re pretending it doesn’t exist. But it’s a strained argument, indeed, that it precludes politicians from acting in the interests of their political party.

@EddieinCA:

When political decisions like this are decided, essentially, by one man? In the past, it was a Sandra Day O’Connor or Anthony Kennedy. Now, it’s likely to be John Roberts. I’d much prefer that they defer “political questions” like this to the elected representatives of the people. (And, yes, I recognize that the system for elections is ever less perfect.)

While I agree that this is the mainline trend, it’s worth noting that one of the two cases here is of a Democratic-leaning gerrymander. Blue state legislatures have the same tools at their disposal and will use it.

The Supreme Court have long shown that they possess sufficient ideologically flexible to justify any decision they care to make. Given enough time, a real (wo)man will find the courage to fix the country’s problems, one way or another. Given the situation, I’d much prefer these justices to do so. As the years roll by and the rot deepens, someone will pick up a flamethrower, and most people will cheer.

I more and more see the Constitution as a milestone around our neck. Is there a single significant problem this country can address?

@James Joyner:

With all due respect, your comment only touches on one small part of my argument. There is ONE party trying to suppress votes across the board. There is ONE party who changes the rules after elections (Wisconsin and North Carolina) they lose. There is ONE party who is making harder for people to vote – especially the young, poor and those of color.

So, yes, one of the gerrymanding cases is a Dem gerrymander, and I’m against that as well as any of the others.

Again, if the election’s aren’t fair, the outcomes won’t be legitimate.

I get this position, in the abstract. But the reality is that such a position is like telling the guy who is doing all the embezzling that he needs to write up some new rules to stop people from stealing from the company.

If we are going to say that we should have equal protection under the law, I do not think it is beyond reason for the Court to therefore see a profound problem when systems are blatantly created to serve one group of citizens at the expense of another.

Indeed, as alluded to above, if we cannot find a way to deal with the fact that our institutions are increasingly empowering the minority to rule the majority, there will be a major political crisis.

This is precisely the problem. Perpetuating a system that has the effect of vote negation–and I don’t know what else you’d call it when majorities of votes aren’t expressed in the outcome–is wrong, it doesn’t matter that “both sides do it.”

Packing and cracking are inherently wrong, and asking political parties (through control of state legislatures) to voluntarily change this behavior when it will necessarily weaken their hold on power is a bit laughable, but that’s what shrugging and saying “oh well state problem” does.

This, to me at least, is exactly the type of issue where the Supreme Court *should* be weighing in. The Founding Fathers didn’t foresee sophisticated software programs that use algorithms to design perfectly partisan district maps.

Gerrymandering, whether it comes from the Democrats or Republicans, is a form of voter suppression. That the SC seems to be punting on this issue is disappointing.

@Jen:

Indeed.

And as I repeatedly note: they did not foresee parties as we understand them, and they especially did not understand the way they would become THE organizing factor in legislative bodies.

The nuts and bolts portions of the Constitution are not equipped to handle this kind of thing, but I do think that the abstract ideals part can (if the Court with let it).

@Steven L. Taylor: have you seen this? American Democracy is Doomed

@Teve: I have, in fact. I started to blog about it at one point but just never did.

@steve: I think people still view the minority rule as an aberration rather than a new status quo.

Except for the ruling minority, who think they are a majority, and come up with any number of fictions (millions of illegals voting!), excuses (if you just don’t let cities vote) and rationalizations (look how many acres of land went for trump!) to attempt to create an appearance of legitimacy.

I think that Roe v. Wade will be eviscerated at the next opportunity (the ban after 6 weeks will be upheld), and then it will be impossible for the majority to keep pretending.

I don’t know what happens after that. It’s all a prelude to death by climate catastrophe anyway.

I honestly don’t know if that last sentence was a joke.

@Steven L. Taylor: I’m on my phone so can’t blockquote easily. I agree in principle that there’s an equal protection issue here. But we’ve never made party affiliation a protected class. Further, the answer to Breyer’s question—What is too much?—is inherently a political rather than a legal one. I don’t think that 5/9 of the Supreme Court should make that call.

That’s pretty easy for a Republican to say, as most gerrymandering in this country has been used to unfairly dilute Democratic votes and increase the number of Republicans in Congress…

@James Joyner: I get it, but if the Court can’t find a way to deal with this, we may well be doomed (not to be hyperbolic, but if a party can construe the rules so that a partisan mix of 48%-52% can lead to those parties winning 3 and 10 seats respectively, then we simply don’t have a democracy and people will eventually figure that out).

And I don’t think parties have to be a protected class for equal protection to apply. It is more fundamental than parties, it is about individual voters and their votes.

Two random provocative based on your reply @James Joyner:

In principle I agree with party not being a protected class. But then, the question becomes, if one part continues a pattern of embracing a certain brand of ethno-nationalism, at what point, in a two party system, does the other party come to be synonymous with other protected classes?

Perhaps, though we also have to acknowledge past Supreme Court decisions that have come up with fuzzy tests for abstract concepts. For example obscenity threshold of “I know it when I see it.” Why doesn’t that apply here as well?

(For the record, I honestly would prefer that the Supreme Court doesn’t try to decide that.)

@EddieInCA:

I actually think those are issues that the Supreme Court should weigh in on. Those are arguably more fundamental than the partisan composition of Congressional districts.

@Steven L. Taylor: @mattbernius: I don’t see a good solution here. We’re ostensibly governed by an extremely out-of-date document written for a completely different polity. But I don’t want SCOTUS as an uber-legislature, simply invalidating policies it finds distasteful. That’s especially true when SCOTUS has time and again recognized the issue in questions as political and outside its province. I wish I knew what the answer was here. Ideally, the citizens of the states would rise up and demand more fair representation. But it’s hard for that to happen when the legislators in question get to pick their voters.

@James Joyner: I guess I don’t think it is out of bounds for SCOTUS to rule on a general standard (like they did with one person, one vote or, for that matter, with separate being inherently unequal). It seems to me that they can act in such a manner without becoming a super-legislature. Setting parameters and ensuring some level of equal protection under the law is not the same thing as making the actual rules.

The alternative is an unrepresentative democracy on the road to a major crisis.

@Steven L. Taylor: So, while there may have been an “intent of the Framers” argument against Brown, “separate but equal” was the opposite of the text and intent of the 14th Amendment. Baker v Carr was more of a stretch, I think, but it articulated a very broad rule that was pretty easy to clarify with a few more cases: that the legislative districts within a state ought represent roughly an equal number of people.

As the various summaries in the OP note, the problem here is that there’s no obvious standard here without legislating outcomes. One could arbitrarily take the most recent set of elections, pretend that it was a single statewide election, and then mandate that districts be drawn in such a way as to approximate a representative distribution. But, aside from having no idea under what Constitutional or Common Law theory we’d do that with, it would then essentially fix the outcome for a decade based on what could well be an idiosyncratic sample.

Alternatively, I guess the Court could rule Single Member Districts unconstitutional and require some sort of statewide allocation. I think that would violate the spirit of the Constitution in a number of ways. But it would certainly be more democratic than what we do now.

@James Joyner:

“I actually think those are issues that the Supreme Court should weigh in on. Those are arguably more fundamental than the partisan composition of Congressional districts.”

On the other hand, the partisan composition of Congressional (and State legislative) districts has a lot to do with why such attempts to suppress votes are made, as the legislators know that in light of the composition of their district, they have nothing to fear from trying to put their thumb on the scale to ensure their party wins.

@EddieinCA:

I think one contributing cause to the US Civil War, and the ferocity with which it was fought, was that the minority in the slave states kept imposing its will on the abolitionist and free state majority, with stuff like the Dredd Scott decision, the fugitive slave act, etc.

It wasn’t the majority that took up arms first, though. It was the minority when they sensed things wouldn’t go their way any more.

Why is this a party protection issue? I think this is voter protection issue. My vote in PA has become even more meaningful as the state is gerrymandered so that other votes matter much more. I think that we should have a fundamental right to vote and to have every vote have the potential/meaning. Why do other people’s votes get to count so much more?

Steve

@James Joyner:

I think the question is why you think that is any more of a stretch than the argument that precludes men from acting in the interests of their sex, or white people from acting in the interests of their race.

@DrDaveT: Those are protected classes under the law.

A judge once famously noted that he may not be able to define pornography, but he knows it when he sees it. Same thing applies to gerrymandering, but a…weakness of the textualists is they seem incapable of handling a situation the founders or previous judges didn’t cover for them to rely on. They have no precedent, and are judges unwilling to use judgement unless they can point to some historical precedent (the worst of them pretend to be relying on precedent while twisting it into something unrecognizable, rather than admit that not just liberal judges interpret things). One could argue (not saying I agree) that the Warren court was a bit too aggressive in setting precedent, but too many of the current crop of judges are far too unwilling to, well, use their judgement. Leading to the recurrent ridiculousness of justices saying “I know this is stupid, but how can we decide on a rationale?” BS and punting.

To me they should simply call the obvious violations stupid and illegal, and THEN leave it up to the politicians to fix. But right now the “umpires” are refusing to call a ball because they can’t find some historical document to tell them the strike zone, and thus allowing obviously discriminatory outcomes the founders wouldn’t have allowed if they’d been aware it was even possible to cheat the ways people do today.

@Steven L. Taylor:

Then what is your solution?

Should they declare that partisan affiliation is a protected class like race, national origin or religion and therefore subject to 14th amendment protection?

Here in Colorado, we’ve solved the problem with a constitutional amendment establishing an independent commission to draw districts (a proposition I strongly supported) – an option that is available for other states if the people there so choose.

But the bigger problem is the lack of any standard that can be evenly applied to make redistricting “fair.” If the SCOTUS is going to decide on this, they need to be able to set a standard that will provide clear guidance on the limits of what legislatures can do across the country. Without that, it’s the Justice Potter Stewart pornography standard which is no standard at all.

@steve:

Ok, what are the criteria to determine if a vote has potential or meaning? How do we determine, specifically, when one vote matters more than another vote? Just take your word for it?

I’m an independent, what about my votes? When I vote independent or third party those votes almost never matter. What should be done to change the system so that my vote matters as much as a partisan vote?

@Andy:

I do not see why an equal protection argument can’t result in a general ruling that districts ought to reflect the state’s partisan balance within some reasonable level of variance.

Cracking and packing clearly result in some votes counting more than others and hence treat different citizens differently.

I honestly don’t think it is all that complicated.

@Andy:

I, personally, would change the system to be more representative.

However, this is not the issue. The issue here is a clear usage of techniques designed to thwart the basic makeup of the state under the current party system. This is about drawing maps to make certain one party dominates.

This is drawing maps to be non-competitive.

And yes, the broader problem is using single seat districts–but that is not going to be resolved by the Court.

An affliction they have in common with too many in Congress, who seem to want the judiciary to solve problems that those in Congress won’t solve…

OMG!!! An actual solution to this problem that so many, for varied reasons, can’t seem to see clearly…it’s funny, Dr. Taylor, how easy it is to solve this problem…

Not to put too fine a point on it, this is ridiculous. It’s not just gerrymandering, if the courts can’t deal with the math in this, how are they going to deal with cases arising from big data or AI?

I Googled around a bit and found a very good 538 article from 2017. The author makes the point that the “efficiency gap”, one proposed method for evaluating fairness of redistricting, is a very simple calculation, readily understood. He also makes the point that it isn’t just math, the legal system can’t seem to deal with empirical information in general. He quotes Oliver Wendell Holmes making the case for empiricism, “

(Now, to be fair, Richard Pozner, Robert Bork and others have not shirked from using econ to destroy the clear intent of our anti-trust laws. (Talk about your activist judging.))

The author also raised what I think is the real issue here. He concludes with,

We’re paying these Justices to deal with hard questions. If they can’t, they should resign.

@Steven L. Taylor:

It’s been thought of before but it’s been rejected. I pulled this from my link archive and will quote the relevant section:

Finally, elevating ideology to be the equal of race, religion and national origin in terms of equal protection would, to say the least, be massive change with equally massive repercussions going forward.

@Just Another Ex-Republican:

I would point out that the result of this was that nine old men spent several years watching pornography to determine whether this particular film was obscene or contained sufficient artistic merit to be permissible speech. They finally gave up. Now, pornography is available anywhere, anytime and the Republic has survived.

I’m not advocating that they abandon the practice of judging. Equity and law are interlinked in our system, for good and ill. But, absent a legal standard grounded in something—the Constitution, the Common Law, some generalizable ethical principle—we would simply substitute the preferences of 5/9 of the Supreme Court for the political judgment of the people’s elected representatives in each of the 50 states. And every single districting plan would inevitably be challenged; it’ll be a lot of work.

Steven and I are in agreement that the practices on display in NC and MD are egregious. I just don’t know what standard SCOTUS can craft for what is permissible partisan gerrymandering and what is impermissible partisan gerrymandering.

@gVOR08 points to one empirical method. I’m amenable to arguments that such a metric is close enough. But I’m not sure what the legal basis for that would be.

@Andy:

That doesn’t mean that I agree with the rejection, or that a notion once rejected is forever off the table.

I am in no way arguing for that. I am arguing that it is clear violation of basic equality of voters to game the system as it is being gamed.

If politicians can pick their voters, rather than the other way around, the election loses democratic meaning.

Look, as I have repeatedly noted, I would scrap our entire electoral system in a way that would eliminate the gerrymandering problem. That is a different discussion. The discussion here is how to manage the system we currently have and that is not going away.

The real fundamental problem is that single seat districts are flawed. But if you are going to keep such a system, it should not be manipulated in this way.

Unfortunately this is a Court, basically the same in ideological composition now, as the one that eviscerated the Voting Rights Act a few years ago. The Court said then that if Congress wants it can legislate the protections that the Court is removing.

This very conservative Court will probably leave to it to the States, and let extreme gerrymandering continue.

@Steven L. Taylor:

Ok, but the long-standing practical and constitutional problems still exist.

A “general ruling that districts ought to reflect the state’s partisan balance within some reasonable level of variance” is not a justiciable standard. The court needs a set of standards for actually proving partisan gerrymandering. In other words, the standard needs to be robust enough that a court can unequivocally know when unconstitutional gerrymandering has occurred and, likewise, when it hasn’t. And, it also must base that standard in terms of constitutional norms and show which provision or norm gerrymandering might violate.

The problems with using equal protection as the basis are still here and relevant. The court and experts have wrestled with this for decades and it doesn’t appear that much has changed.

The point is that if you want to use equal protection as the constitutional basis against gerrymandering because it doesn’t treat partisan ideology equally, then I think it would be very difficult to limit such protections to just gerrymandering. Once you single-out partisan ideology as a status requiring constitutional protection, then what is the basis for denying partisan ideological protection in other areas?

You’re right that’s a different discussion, and it’s one I’m not making here.

I’m just pointing out that it’s not easy or trivial for the SCOTUS to effectively address this issue for all the reasons previously given. The problems with effectively addressing this in a comprehensive way through court action still exist after decades of debate and consideration. If someone could come up with a coherent justiciable standard based on the constitution as it is and not as we would like it to be, then I would probably get behind it. But after many decades of trying, we are still at the Potter Stewart pornography standard and because of that, I think it’s better to deal with this at the state level as many states have done successfully.

@Andy:

That may be a fair position, but I wasn’t suggesting that a one line suggestion in a comment box was going to provide the full solution.

@James Joyner: This court watching porn might get some of them to loosen up 🙂

Porn is generally available, for sure, but lots of it, such as child porn and snuff films to name two, are still illegal (and should be). I suppose those fall into the “generalizable ethical standard” you want. What about Stephen’s phrasing that “If politicians can pick their voters, rather than the other way around, the election loses democratic meaning”? Isn’t that a reasonably clear ethical standard? Politicians can’t be trusted to choose their voters? You agree what’s going on in a couple states is egregious, so why do you have a problem with a co-equal branch of government saying: “That’s BS. It violates basic principles of democracy and as judges for “the people of the United States” (not we the people of a political tribe) it is illegal. Do better.” Even threw in a Constitutional reference for you there 🙂 (albeit the preamble). Yes, it’s setting a precedent. But it’s past time someone pointed out that even in the US, non-partisan district building is far superior to letting the fox draw the barriers around the hen house.

To go back to Robert’s famous (and seriously flawed) analogy: pretending Supreme Court judges are just umpires calling balls and strikes is stupid. It pre-supposes an agreed set of rules (and even then, we argue about balls and strikes all the time). But when situations come up not covered by the rulebook, who updates the rules? Logically, and in most cases I agree with you, it should be Congress and the legislative branch. But what about when the situation in question is coming up because of legislatorial abuse? One of the other checks and balances HAS to come into play, or the system tilts into instability.

Not saying it’s simple, and I agree I don’t want every districting plan being challenged in the court. I just want the electoral map equivalent of snuff films to be outlawed.

@Andy:

This conversation is problematic, as I reject this premise (and I have noted multiple times). I am not asking for ideological equality. I am asking for not allowing the electoral rules to be gamed to create specific outcomes.

I am not asking for a test based on ideology. I am asking for a test based on competitiveness within the existing electoral system.

The reality is that our system creates the conditions for a very stable two party system. For the sake of this discussion I don’t care what the ideological content of the parties is. For the sake of this discussion we have a game with rules that produces winners and losers. What they are doing in NC and MD unfairly creates conditions in which one team wins overwhelmingly when it shouldn’t.

The worst part about that is the winner continues to get to make the rules of competition so that they can continue to win.

I will say for the umpteenth time: the main problem is single seat districts. There is no perfect way to draw them. I understand the basics of that problem and why the Court would not want to get involved. That doesn’t change the fact that if the system can be gamed as it is, we don’t have a democracy. That strikes me as a problem, to put it mildly.

I am not suggesting it is easy nor trivial.

@Steven L. Taylor:

Ok, but the constitutional justification you gave is based on using equal protection as the basis for a ruling and the way equal protection works is by granting protections to discrete groups of people. And the court has already decided that equal protection applies in the case of redistricting based on race, which is banned because it intentionally dilutes votes. Applying equal protection to partisan affiliation to ensure that partisan votes are not diluted is, as a practical matter, the same thing.

The entire problem, as we both agree, is that one partisan group is using redistricting to unfairly diminish the political power of another partisan group. If we are going to use equal protection as the basis to correct that (like the SCOTUS did with race), then you can’t avoid looking at ideology any more than we can ignore looking at race when assessing whether redistricting has violated the ban on racial vote dilution. And that is on top of the practical problems detailed in the previous analysis I quoted.

and

I understand that, agree and have not disputed any of that here. Gerrymandering IS a problem and single-seat districts are a big reason why. My skepticism of broad-ranging SCOTUS action is not because of any love for gerrymandering, nor is it because I think what NC and MD have done is legitimate, nor does it have anything to do with the problems of single-seat districts.

In other words, I agree with you on the problem, I do not agree with you on the solution you proposed.

Then I guess I misinterpreted this:

I was simply responding to your suggested solution and statement that it isn’t complicated by explaining why I think it won’t work and why I think it actually is complicated.

To reiterate, I want to end partisan gerrymandering as much as anyone – probably more. But the process and the way we achieve desired goals matter a great deal to their legitimacy, outcome and third-order effects. This is one problem I don’t think the SCOTUS can definitively solve without creating a host of other problems because of all the reasons previously cited by the scholars who study this.

I wish there was an easy, uncomplicated way the Court could end gerrymandering, but there doesn’t appear to be one.

@Steven L. Taylor:

Agreed, but as a New Hampshire resident, I can attest that there are also flaws with multi-member districts, not the least of which is an absolutely huge House (400 state reps) for a fairly small state! We all have 3 state reps and 1 state senator.

It would be interesting to see how multi-member districts would work on a national level.

@Jen: It would depend on the system deployed.

@Andy:

Sure. And there isn’t.

I get the position that SCOTUS shouldn’t insert itself. I simply do not believe that it can’t.

Of the less than optimal solutions at the moment, I think SCOTUS is the best route available. It may be the only one.

I’m way late here, but perhaps the solution that Dr. Joyner prefers is that every state go through what my state of Michigan just did: vote on a proposal to create a (theoretically) non-partisan redistricting commission.

@Franklin:

As a matter of public policy, I think that’s the right way to go. Many states have gone that route. And the Supreme Court ruled that that process is Constitutional back in 2015.

@Franklin: Such commissions are far from perfect but are better than what most states have. But what are the odds that NC Republicans or MD Democrats are going to impose that on themselves?

@Kathy: historical fact with frightening implications… tho with fascism succeeding, all out war may not even be “necessary”.