Signing Statements Raising Hackles on the Hill (Updated)

The Senate is holding hearings this week on President Bush’s practice of attaching presidential signing statements to legislation he signs into law:

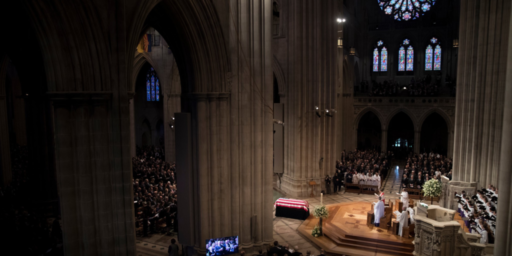

Sen. John McCain thought he had a deal when President Bush, faced with a veto-proof margin in Congress, agreed to sign a bill banning the torture of detainees.

Not quite.

While Bush signed the new law, he also quietly approved another document: a signing statement reserving his right to ignore the law. McCain was furious, and so were other lawmakers. …

Rather than give Congress the opportunity to override a veto with a two-thirds majority in each house, he has issued hundreds of signing statements invoking his right to interpret the law on everything from whistleblower protections to how Congress oversees the USA Patriot Act.

“It means that the administration does not feel bound to enforce many new laws which Congress has passed,” said David Golove, a law professor at New York University who specializes in executive power issues. “This raises profound rule of law concerns. Do we have a functioning code of federal laws?”

Signing statements don’t carry the force of law, and other presidents have issued them for administrative reasons — such as instructing an agency how to put a certain law into effect.

There are multiple issues at work here; Congress often passes the buck to the executive branch to flesh out the details of implementing laws, particularly in cases where legislators are too divided to come up with specific guidance–hence the explosive growth of the Federal Register in the post-World War II era.

On the other hand, as the president’s critics point out, he has the opportunity to veto legislation that he believes infringes on the independence of the executive branch; indeed, if Bush believes that a proposed law is unconstitutional, his obligation to uphold the Constitution would suggest he must veto it, rather than leaving it to the courts to eventually decide.

Update: Ed Brayton at Positive Liberty has more extensive thoughts on this matter, along with some quotes from conservative constitutional law scholar Bruce Fein that underscore the dubious legal and constitutional status of portions of Bush’s statements.

Bush does seem to regard “veto” as a four-letter word…

indeed, if Bush believes that a proposed law is unconstitutional, his obligation to uphold the Constitution would suggest he must veto it, rather than leaving it to the courts to eventually decide.

I guess it’s more subtle than that. What I see the gimmick as being is, “I endorse this law to the extent that it may be interpreted as constitutional, while reserving the right to reject any unconstitutional interpretation of it.”

So, with e.g. the McCain anti-torture bill, Bush would simply interpret it consistent with his lawyers’ sweeping notion that Article II provides exceptions whenever Bush deems them necessary. No duty to veto, because Bush will enforce it, except when it’s actually needed.

(Looking forward to reading Jane Mayer’s bit on Addington in the New Yorker this week … oh, and on unrelated topics of OTB interest, Greg Sargent finds the administration tongue-tied when he asks why they’re not going ballistic on the Wall Street Journal for its “treason.” Heh, as they say.)

Assitant Attorney General under Clinton:

I suspect that if McCain, or anyone else of either party, was elected president, was faced with a bill that could impact the ability of the executive branch to carry out some of their constitutionally mandated duties (such as defending the country) and faced with a majority that could overcome a veto, would likely take the same path.

We don’t know the constitutional impact of the ‘signing statement’. You could make a case for it and against it. There is supposed to be a certain amount of tension between the branches that forces them to pull against each other.

Thanks for linking the paper, Curt, though I have a hard time respecting the intelligence of anyone who writes “as some have commentated,” on the very first page no less.

But could you please cite the page with the “no duty to veto” quote? I’ve skimmed text and notes, and Adobe search isn’t finding it either. Merci …

Geez, I’m sorry Anderson, I linked the wrong paper….doh.

Here is the link to the paper written by Dellinger. A search should bring up that sentence real quick.

Thanks, Curt. I wish Dellinger had given an example other than Jefferson’s, as I don’t consider T.J. a model of ethical probity, personal or professional.

Given the nature of modern legislation, however, it’s quite arguable that an entire bill needn’t be vetoed because 1 provision out of 5,000 pages is of questionable constitutionality. The signing statement then becomes a Big Hint by the President for any interested party to challenge the law.

I’d previously inclined to JJ’s “duty to veto” theory, so thanks much for linking the article.

You got it Anderson, and I agree completely that it would be foolhardy to veto a whole bill due to one provision possibly unconstitutional.

Check out Dellingers memo he wrote in 1994 to a judge that has even more substance.