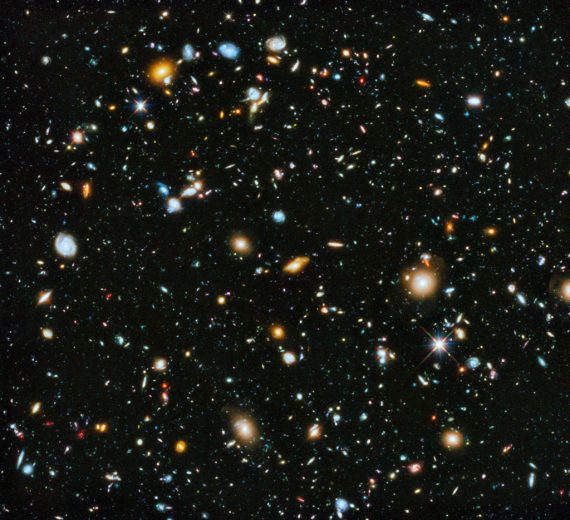

100,000,000 Habitable Planets In Our Galaxy Alone?

A new theory posits that planets capable of supporting life may be far more common than previously thought.

There could be a lot more planets capable of supporting life in our own galaxy than we can possibly imagine:

How many planets in the Milky Way might harbor complex life? A group of researchers now suggest the number may be as high as 100 million. However, other scientists pointed out potential flaws in this estimate and warned this exercise may be too speculative to be useful.

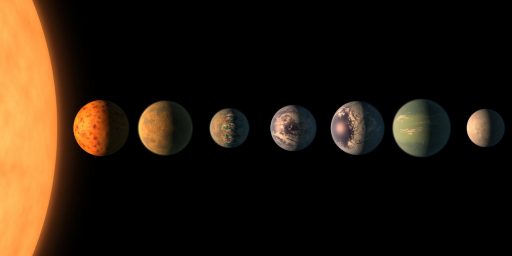

Astronomers have so far confirmed the existence of more than 1700 exoplanets and may soon confirm thousands more. And even before that, scientists have attempted several different measures of how likely life might be on other planets. For instance, there’s the Earth Similarity Index that looks for worlds similar to Earth, while the Planetary Habitability Index seeks out worlds that might support not only life as we know it, but also more exotic organisms.

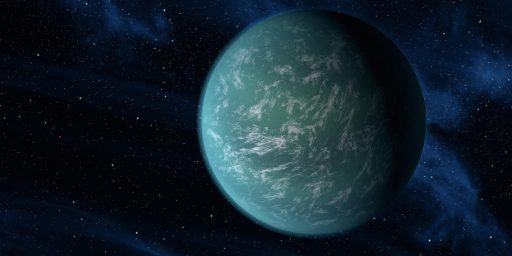

However, these previous measures did not look for worlds that might be likely to host biology more complex than microbes. Now researchers have developed a new measure for estimating how many planets and moons could harbor complex, diverse, multicellular life.

“Complex life in no way implies intelligent or technologically capable forms of life,” says lead study author Louis Irwin, professor emeritus and former chair of biological sciences at the University of Texas at El Paso. “A planet covered in mosses and fungi-like organisms that feed on the mosses would qualify as a complex biosphere.”

The scientists developed a formula that considers seven factors that might promote the evolution of complex forms of life on planets and moons. They deemed four important for life in general: a material that life could grow on; energy to sustain life; chemistry that allows the creation of complex molecules such as organic polymers; and a liquid solvent for such chemistry to occur in, such as water. They regarded three important for the evolution of complex life: complex environments that can foster diverse life; a range of temperatures warm enough for biology to occur but cool enough to not destroy biological compounds; and age—the older a world is, the more time it has had to evolve complex life.

Irwin and his colleagues then used their formula to compute a “Biological Complexity Index” (BCI), which rates planets and moons on a scale of 0 to 1.0 for how well they might support multiple forms of multicellular life.

“It is important to note that the Biological Complexity Index is not based solely on life as we know it,” Irwin says. “We do believe that polymeric chemistry and liquid solvents are essential, but in theory, atoms other than carbon and liquids other than water could fulfill the basic requirements for living systems. We do believe that carbon and water are much more likely to be favored by living systems, but until we find a sufficient number of examples of life elsewhere in the universe, we believe that it would be scientifically improper to restrict our consideration only to life as we know it on Earth.”

After surveying the list of confirmed exoplanets, Irwin and his team suggested 1.7 percent of these worlds had BCI ratings higher than Europa, a moon of Jupiter suspected to possess a hidden ocean that might harbor life. Based on an estimate of 10 billion stars in the Milky Way and assuming an average of one planet per star, the researchers arrived at their estimate that there could be 100 million worlds in the galaxy that could foster complex life. They said this constituted the first quantitative estimate of the number of such worlds that is based on observable data.

This is by and large all speculation at this point, of course, but the idea of 100,000,000 or more planets capable of supporting life doesn’t seem nearly as far fetched as it used to not very long ago.

There was a time, after all, when we weren’t even sure that there were planets outside of the Solar System. Most scientists assumed that there were, of course, since it seemed unlikely that there was something unique about our star that would have made it different from every other star in the universe, but there wasn’t proof for that assumption. The proof came thanks to satellites such as the Kepler observatory and others which have used precise measurements of the light eminating from neighboring stars to detect the passage of planets in front of them, along with other methods. Because of that, we have discovered hundreds of planets orbiting nearby stars, including several in the so-called “Golidlocks Zone,” meaning that they are within the distance from their star generally believed to be necessary to support life, or at least life as we know it. We haven’t been able to prove that there’s even rudimentary forms of life on any of these planets yet, of course, but there have already been several discussions among astronomers about how we might be able to do that, including efforts to measure the content of a planet’s atmosphere for signs that it contains the byproducts of life. Of course, even proving that there’s some kind of life on a distant world would only be the first step. Without actually traveling there, it would be far more difficult to determine how complex the lifeforms on that planet might be, and absent interception of radio signals there would be know way of knowing if any of these planets support life approaching the same level of technological achievement that we have.

Keeping all of that in mind, it strikes me that the most logical conclusion is that there is indeed life elsewhere in the universe, including intelligent life that may likely have reached a level of achievement far beyond our current levels. On some level, this is simply the recognition that there is something incredibly arrogant about the idea that we are somehow unique in the universe. With the tens of billions of years that have passed since the universe came into existence, the idea that life has come into existence, flourished, and achieved intelligence elsewhere makes perfect sense, which is why we shouldn’t be surprised if and when proof of such a thing is eventually found somewhere at some point in time.

Perhaps this logic will turn out to be faulty in some way. Maybe we really are all alone in the universe. It will be up to science to try to find the answer to that question. Something tells me that we aren’t alone, though.

Photo credit: NASA/ESA

I dunno. One of the problems here is that even Earth wasn’t Earth-like for most of its history. Indeed for three-fourths of Earth’s history, Earth supported only microbial life. It wasn’t until around 550M years ago that we started having complex multicellular life and even then , it was all in the sea. Earth only became a truly Earth type planet around 300M , when reptilian life started hitting its stride. The point is that most of those Earth-type planets may not have Earth-like life as we know it. They may just have empty continents surrounded by oceans covered by algae.

As for intelligent life, conscious intelligence has evolved only once on one twig of one branch of the tree of life on Earth. We used think that intelligent life was the inevitable goal of evolution , but most biologists no longer think so. Like you I have faith that there is intelligent life out there, but I don’t think the science backs it up. We may be alone.

Still, science isn’t everything. Lets have hope, and dream of a Star Trek type Universe. It’s still possible.

They left out an important element, a strong magnetic field that would deflect solar and cosmic radiation.

@Ron Beasley:

Yep. Earth is actually pretty special.

Remember when we thought Venus might be a hot tropical planet with dinosaur type life and Mars was an old, dying planet with canals and ancient intelligences? That was some fun old science fiction.

@stonetools: You are correct, although Mars is theoretically in the life zone it became a dead planet when the magnetic field went away and as a result most of the atmosphere was swept away by solar winds.

@stonetools: I kind of hope that there isn’t life out there. If there is, and we meet it (which we probably would at some point), I see more bad outcomes than good.

@stonetools:

That depends on how you define conscious intelligence. I think a strong case can be made for some cetaceans that would add another twig on our branch and a strong case can be made for some cephalopods that would put intelligence on another branch.

@Grewgills:

Yeah, well cephalods and cetaceans don’t have reality shows and Tea Party conventions so that proves we are uniquely intelligent….. Wait , what?

Probably a good time for more GOP cuts to the space program.

It looks to me like they’re mainly restating a version of the Drake equation. The problem with that kind of analysis is that even one unknown can dominate the statistics. Yeah, there *could* be 100 million planets capable of bearing life (although whether they *have* life is another question). But the uncertainties in that calculation have to be pretty close to … a hundred million or so.

@Hal_10000:

So, 100 million give or take 100 million.

Yes. I think a better way of stating their result is that the current state of exoplanet science does not rule out a Galaxy brimming with life. Given certain assumptions, what we are seeing is consistent with that idea. But I wouldn’t go beyond that.

Kind of like believing there is a God and he created you in his image, and built this planet around you for your own personal pleasure, and when things aren’t quite up to snuff you can just call him up and he will listen and then make it all hunky dory for you and you alone because you are God’s favored one?

Like that?

(sorry, I go there when people mention arrogance and religion just naturally follows in my brain)

Playing Devil’s Advocate here, suppose you’ve got the sort of technology that would let you construct self-sufficient colonies on places like Mars and the Moon. Suppose you’ve the sort of technology that would interstellar travel possible, whether as slow moving “generation ships” or the FTL drives beloved by science fiction readers. Suppose also you’ve got an economy big enough to fight world-spanning wars (and that you aren’t constantly doing so), large enough to affect the environment of your planet. Finally suppose you’re an expanding, exploring culture with some sort of baked in “‘urge to travel.”

None of these seem hugely improbable. Given all this, though. and 13 billion years to work with, what are the odds that one or more species would expand into the Galaxy? My gut feeling is that truly uninhabited solar systems ought to be as rare as say vacant houses in San Francisco — and yet we’ve no evidence at all that anyone is at home on the thousands of solar systems we’ve discovered in the last few decades, no evidence as yet that any other species is interested in communicating.

Which seems ominous.

@mike shupp:

It’s a pretty big galaxy. No need to start worrying we are alone just yet. It’s like exploring Kansas and concluding that mountains don’t exist.

I would say that the evidence is that life is most likely out there, simply because lots of possibly life supporting planets , but intelligence is rare. That seems to be the lesson of Earth.

Also too, time is deep. A thousand alien species could have come into being, survived a million years, and died out before the first fish with legs ever slithered onto land on Earth. Homo Sapiens has been around just 200,000 years.

I think we might have a galaxy with a handful of intelligent species, separated by millions of light years. We’ll need those FTL drives and ansibles to communicate with them.

Okay, fwck it, I’m going to finish that FTL drive I’ve been working on.

On the gripping hand, perhaps we should be worried if we AREN”T alone. http://xkcd.com/1377/

@Stonetools:

I certainly haven’t seen any sign of intelligence yet.

Something we as a species haven’t been able to come to grips with is the possibility that space travel is legitimately impossible. Given the possible economic resources available to a society that has already consumed some of those resources to get to a technological level capable of sending people into outer space, perhaps no planet that supports intelligent life can hold enough of said resources.

And you see what space does to organisms like us that rely on gravity as a postulate to our evolution. Yet evolutionarily we will expand into every habitat and niche we can as long as we are able. I wonder if space travel is the point at which intelligent species hit the wall against expansion, and they don’t realize it’s a wall until they’ve already mined their planet dry.

On the other hand, consider the fact that our industrial revolution uses the bio-matter (oil) created from at least five or six previous mass extinctions in our planet’s billions-year-long history as primary fuel. The “incubation period” for a planet to produce an intelligent species with enough resources to achieve space travel is probably a lot longer than Fermi thought.

@stonetools: true, we really don’t know much at all about any of this- our own scientific arrogance makes us think there can only be “life” like our own definition.

we have come a long way in the past 50 yrs, but we just opened the box, can’t really see (let alone imagine) what’s in there. “we” could be remnants of one of those planets that “died” long ago- probably not, but not all that unlikely.