Court Rules That Accessing OTB At Work Isn’t A Federal Crime

A Federal Court rejects an effort to significantly expand the application of a law designed to target computer hacking.

Okay, so the case didn’t really involve someone reading Outside The Beltway at work in violation of company computer use polices (of course I know none of you would ever do that right?), but the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals did rule yesterday that the Department of Justice cannot use a law designed to prosecute computer hacking to criminally charge someone who violated their company computer use policies:

Employees may not be prosecuted under a federal anti-hacking statute for simply violating their employer’s computer use policy, a federal appeals court ruled Tuesday, dealing a blow to the Obama administration’s Justice Department, which is trying to use the same theory to prosecute alleged WikiLeaks leaker Bradley Manning.

The case, decided by the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, concerns the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, which was passed in 1984 to enhance the government’s ability to prosecute hackers who accessed computers to steal information or to disrupt or destroy computer functionality.

At least, that’s what the court says is the act’s purpose.

(…)

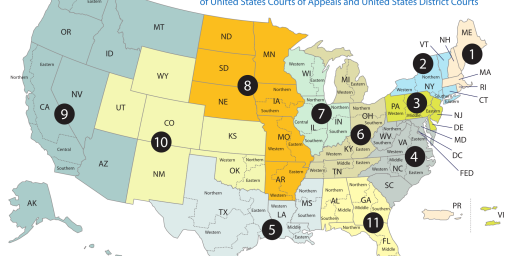

Tuesday’s case considered an appeal by defendant David Nosal, who had worked for an executive search firm and was charged with, among other crimes, three CFAA counts for allegedly aiding and abetting his former colleagues to supply him with company data that his co-workers were authorized to access but forbidden to divulge. The decision by the nation’s largest federal appeals court, which covers the western United States, reverses the same circuit’s 2-1 ruling last year that said no hacking was required to be prosecuted as a hacker under the CFAA.

The 9th Circuit covers Alaska, Arizona, California, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Oregon and Washington.

The outcome conflicts with at least three other circuit courts of appeal nationwide, which means the Supreme Court could take up the issue soon. The San Francisco-based appeals court noted the split and urged its sister circuits to reconsider their rulings. (.pdf)

The same legal theory was used to prosecute Lori Drew, who was charged criminally for participating in a MySpace cyberbullying scheme against a 13-year-old Missouri girl who later committed suicide. The Los Angeles federal court case against Drew hinged on the government’s argument that violating MySpace’s terms of service was the legal equivalent of computer hacking and a violation of the CFAA. A federal judge who presided over the prosecution tossed the guilty verdicts in July 2009, and the government declined to appeal.

The feds used the same theory to get hacking convictions of two New Jersey men who used computer scripts to help them buy, with real money, lots of concert tickets from Ticketmaster.com, which they later scalped.

Accused WikiLeaks leaker Bradley Manning is also accused of, among other things, breaching the CFAA by allegedly exceeding his authorized access of a government computer and providing files to secret-spilling site WikiLeaks. The prosecution doesn’t allege, however, that Manning actually broke into any computer system.

When it comes to a criminal statute, there is a general principle that Courts at all levels, State and Federal, have followed from time immemorial. Put in its most basic language, that principle says that criminal statutes should be construed as narrowly as possible while remaining consistent with the text of the law, and the intent of the legislature. That’s why it’s somewhat surprising not only that the Federal Government is arguing for an interpretation of the CFAA that is so broad that even something as trivial as lying about your height, weight, or eye color when filling out a Match.com profile would technically be considered a violation of the law, and that several Federal District Courts and Circuit Courts of Appeal have apparently gone along with that argument.

The reason to narrowly construe criminal statutes should seem self evident. The broader a statute is construed, the more potential activity that might otherwise be totally innocent ends up being considered a crime. Additionally, a statute that was intended to address a single issue (in this case computer hacking) can suddenly become a powerful weapon in the hands of Federal Prosecutors who can use the threat of potential criminal charges to extract a wide variety of concessions from a potential Defendant. Ken at Popehat describes the danger that an overly broad interpretation of a law like the CFAA creates quite well:

The danger is not that the government will prosecute everyone who lies about their weight on Match.com or lets their 12-year-old register on Facebook or visits Popehat from Canada without sending us donuts. The danger is that the government will selectively prosecute people they don’t like — that the government will use this statute to scratch their “there oughta be a law” itch when they are mad at someone who hasn’t actually committed a real federal crime.

There are already enough provisions of the United States Code that allow the government to do this, the most notable one being the statute that makes it a crime to lie to any federal agent (even when you’re not under oath) which has ensnared people like Martha Stewart and Scooter Libby even though prosecutors were unable to get the underlying charges to stick against either Defendant. The broad authority granted by the interpretation of the CFAA would be yet another weapons that a United States Attorney could use to get a conviction when they can’t really prove that anything truly wrong happened beyond a reasonable doubt.

Judge Alex Kozinski, a Reagan appointee who has been consistent libertarian voice on the 9th Circuit for decades now, rejected the government’s argument in an opinion that spoke for all but two of the eleven members of the Court that heard the case in an en banc appeal, rejected that argument:

[W]e hold that the phrase “exceeds authorized access” in the CFAA does not extend to violations of use restrictions. If Congress wants to incorporate misappropriation liability into the CFAA, it must speak more clearly. The rule of lenity requires “penal laws . . . to be construed strictly.” United States v. Wiltberger, 18 U.S. (5 Wheat.) 76, 95 (1820). “[W]hen choice has to be made between two readings of what conduct Congress has made a crime, it is appropriate, before we choose the harsher alternative, to require that Congress should have spoken in language that is clear and definite.” Jones, 529 U.S. at 858 (internal quotation marks and citation omitted).

The rule of lenity not only ensures that citizens will have fair notice of the criminal laws, but also that Congress will have fair notice of what conduct its laws criminalize. We construe criminal statutes narrowly so that Congress will not unintentionally turn ordinary citizens into criminals. “[B]ecause of the seriousness of criminal penalties, and because criminal punishment usually represents the moral condemnation of the community, legislatures and not courts should define criminal activity.” United States v. Bass, 404 U.S. 336, 348 (1971). “If there is any doubt about whether Congress intended [the CFAA] to prohibit the conduct in which [Nosal] engaged, then ‘we must choose the interpretation least likely to impose penalties unintended by Congress.'” United States v. Cabaccang, 332 F.3d 622, 635 n.22 (9th Cir. 2003) (quoting United States v. Arzate-Nunez, 18 F.3d 730, 736 (9th Cir. 1994)).

This narrower interpretation is also a more sensible reading of the text and legislative history of a statute whose general purpose is to punish hacking—the circumvention of technological access barriers—not misappropriation of trade secrets—a subject Congress has dealt with elsewhere. Therefore, we hold that “exceeds authorized access” in the CFAA is limited to violations of restrictions on access to information, and not restrictions on its use.

It strikes me that Kozinski is largely correct here. If Congress wants the CFAA to apply to these types of situations, then it could amend the law to provide for that. In fact, James Joyner noted here just this past September that such an Amendment was pending in the Senate Judiciary Committee, however it doesn’t appear that any action has been taken on the measure due in no small part to the concerns that were being raised about the legislation at the time and the fact that the Committee’s Chairman, Sen. Patrick Leahy had expressed concerns about the broadness of the changes the Dept. of Justice was requesting. Whether that legislation will be revived in the future is unknown, but Congress has the option to do so and they would do it publicly so that the American people would have the right to voice their opinion on a potentially important issue. It simply isn’t appropriate for the Courts to be taking a law passed into law in 1994 and applying such a broad interpretation to it that any number of seemingly innocent activities are dragged into the category of “Federal Crime.”

Kozinski also addressed the decisions of other Circuit Courts and found them unpersuasive:

We remain unpersuaded by the decisions of our sister circuits that interpret the CFAA broadly to cover violations of corporate computer use restrictions or violations of a duty of loyalty. See United States v. Rodriguez, 628 F.3d 1258 (11th Cir. 2010); United States v. John, 597 F.3d 263 (5th Cir. 2010); Int’l Airport Ctrs., LLC v. Citrin, 440 F.3d 418 (7th Cir. 2006). These courts looked only at the culpable behavior of the defendants before them, and failed to consider the effect on millions of ordinary citizens caused by the statute’s unitary definition of “exceeds authorized access.” They therefore failed to apply the long-standing principle that we must construe ambiguous criminal statutes narrowly so as to avoid “making criminal law in Congress’s stead.” United States v. Santos, 553 U.S. 507, 514 (2008).

We therefore respectfully decline to follow our sister circuits and urge them to reconsider instead. For our part, we continue to follow in the path blazed by Brekka, 581 F.3d 1127, and the growing number of courts that have reached the same conclusion. These courts recognize that the plain language of the CFAA “target[s] the unauthorized procurement or alteration of information, not its misuse or misappropriation.” Shamrock Foods Co. v. Gast, 535 F. Supp. 2d 962, 965 (D. Ariz. 2008) (internal quotation marks omitted); see also Orbit One Commc’ns, Inc. v. Numerex Corp., 692 F. Supp. 2d 373, 385 (S.D.N.Y. 2010) (“The plain language of the CFAA supports a narrow reading. The CFAA expressly prohibits improper ‘access’ of computer information. It does not prohibit misuse or misappropriation.”); Diamond Power Int’l, Inc. v. Davidson, 540 F. Supp. 2d 1322, 1343 (N.D. Ga. 2007)(“[A] violation for ‘exceeding authorized access’ occurs where initial access is permitted but the access of certain information is not permitted.”); Int’l Ass’n of Machinists & Aerospace Workers v. Werner-Masuda, 390 F. Supp. 2d 479, 499 (D. Md. 2005) (“[T]he CFAA, however, do[es] not prohibit the unauthorized disclosure or use of information, but rather unauthorized access.”).

Given that there is a conflict between the Circuits, there is a good chance that this case will be taken up by the Supreme Court, most likely not until its next term at this point. Let’s hope they get it right.

Here’s the opinion:

Doug, I have to admit it, when I read the headline,

…. I was thinking that OTB was “Off Track Betting”

@al-Ameda:

Play the horses, do you?

Good ruling (meaning one I agree with, of course. I have no basis to judge the merit from a legal perspective), and let’s hope it stands.

@KariQ:

I’m from a betting family. Me? Not so much.

I agree with you on the result – criminal charges should be reserved for criminal activity, not for employee violation of company computer usage policies. That’s another matter.

I don’t say this too often so when it happens I really mean it: Great decision by the 9th Circuit. Separate but related topic: Kozinski is one of my all-time favorite judges. A true giant in the conservative-libertarian community.

@Tsar Nicholas:

Kozinski is a judge who deserved to be considered for SCOTUS in my opinion.

@Doug Mataconis: Kozinski is actually as close to a libertarian as you’ll find. Perhaps if Thomas is forced off the court (fortas was forced out for a lot less …) Obama might consider Kozinski?

@Doug Mataconis: Indeed. Speaking of which, I still haven’t figured out why Reagan went with Kennedy with Kozinski also sitting there on the 9th Circuit, having worked in Reagan’s White House, and being so much younger. Sigh.

@Doug Mataconis:

You think Republicans want purist libertarians on the supreme court?

Isn’t there already a law about divulging company secrets or other espionage or privacy charges? Wouldn’t that have worked better, that they were stealing the information by giving it to who they weren’t supposed to?