D.C. Traffic and Terrorist Attacks

Jerry Seper asks “Is D.C. ready for terrorist attack?” in today’s Washington Times. His premise: The city can’t even deal with routine traffic accidents, how could it handle a coordinated terrorist strike?

Two unrelated traffic accidents within an hour of each other yesterday in Northeast shut down two major highways during the busy morning commute, causing massive gridlock and seemingly endless delays — but also providing an ominous warning: What if it had been a terrorist attack?

[…]

Even the agencies assigned the task of responding to a terrorist attack could contribute to the problem: A Code Red declaration by the Department of Homeland Security — meaning that an attack was imminent or had taken place — could result in an immediate lockdown of public and government facilities and restrictions on public travel. Under the direction of Homeland Security, emergency personnel and equipment would need to be directed to the area, transportation systems would be “redirected or constrained,” and public and government facilities could be closed.

[…]

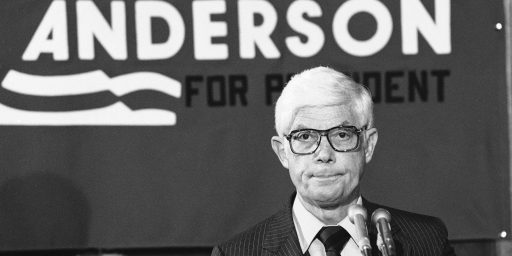

Lon Anderson, spokesman for AAA Mid-Atlantic, said the main commuter routes in the Washington area operate at maximum capacity, leaving almost no alternative if one becomes blocked because of an accident. “Add a major incident that takes away a major commuter route and it doesn’t mean that everything slows down. It means that everything stops,” Mr. Anderson said.

Gridlock is not uncommon in the D.C. area because of incidents involving national security or other law-enforcement concerns, dating to at least 1998, when an Alexandria man threatened to jump off the Woodrow Wilson Bridge and stopped traffic for more than five hours. D.C. police shot him in the leg with a beanbag bullet and he jumped into the water. The man survived, but the incident backed up Beltway traffic for more than 20 miles.

In March 2003, Dwight Ware Watson, dubbed the “Tractor Man,” brought much of Washington to a standstill when he decided to protest tobacco-subsidy cuts by driving a tractor into a Constitution Gardens pond on the Mall. U.S. Park Police cordoned off the area from the Washington Monument to the Lincoln Memorial. The federal government emptied several nearby offices and closed off major traffic arteries. Over the two days of the siege, four consecutive D.C. rush hours saw massive traffic jams.

Major evacuations of federal buildings in the District also have been prompted by suspicious events, forcing an exodus out of the city. In 2005, a pilot’s errant flight into restricted D.C. airspace May 11 prompted evacuation of the White House, the U.S. Capitol and the Senate and House office buildings, but also exposed a breakdown in communications between federal agencies and city officials, who did not know about the evacuation because they had disconnected a communications line between the Federal Aviation Administration and the Metropolitan Police Department.

After 24,000 military personnel and civilians who work at the Pentagon were evacuated on September 11, along with much of official Washington, highway gridlock took over in the nation’s capital. Police also cleared the Capitol and all House and Senate office buildings, and the drive out of the city took hours.

John Robb notes that “systems disruption . . . is a low cost, high impact method of conducting strategic warfare (with dimensions of all three types of warfare: attrition, moral, and connectivity) against developed states. Although most of the disruption activity to date has been focused on strategic resources, the method can be easily applied to urban to reduce general economic activity.”

Unfortunately, this strikes me as a case where, as Shimon Peres put it, “If a problem has no solution, it may not be a problem, but a fact, not to be solved, but to be coped with over time.” Any attempt to fix the D.C. infrastructure will lead, probably faster than the construction is completed, people to change their living and working patterns to get back to gridlock. Essentially, Parkinson’s Law as applied to big city traffic.

The only plausible situation, it seems to me, is one that is a political non-starter: Decentralization of the federal government. From both a financial and a security standpoint, it makes sense to disperse most federal agencies off to the hinterlands, which would not only be far cheaper in terms of office rent and reduced cost of living subsidies but spread the traffic demands sufficiently as to make it virtually a non-issue. Unfortunately, agency heads want to be as close to the flagpole as possible.

I’ve been advocating Federal decentralization for decades! Most Cabinet and Agency offices could be put out in the field, leaving core headquarters in DC to deal with Congress and the White House.

Why isn’t AG located in the Mid West? Couldn’t Commerce work as easily from Chicago as Pennsylvania Avenue? Put the offices where the constituents can see them–and be part of them. Let people see their tax dollars working in their states directly.

Certain agencies don’t have constituencies, so to speak. State and DOD, for instance, have such wide constituencies that it really doesn’t matter that they’re in DC.

Move HUD to St. Louis; Education to Hartford; Energy to Houston or Fairbanks.

BREAK UP THE BELTWAY!!

Don’t let the politicians get ideas. I’m sure Sen. Shelby would love to move the entire DoD down to Huntsville. Heck, he’s got a lion’s share of it already 🙂

DCL: Huntsville would be a far better location than Arlington from a cost perspective and it’s a gorgeous area to boot.

The only real downside is that it would remove the easy moving from job-to-job that occurs for contractors and civil servants with everything in DC.

When CIA–through force Byrd–moved one of its offices to the WV panhandle, they told Congress that they’d never be able to staff the new facility. Instead, they had to deny transfers because so many wanted to live outside the DC area.

Better cost-of-living, better schools, lower crime… just generally better lifestyles available.