Fourth Circuit Appears Skeptical Of Government’s Arguments Defending Trump’s Muslim Travel Ban

The Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals heard argument yesterday in the appeal of an order barring travel from six Muslim countries, and it didn't appear to go well for the attorneys defending the ban.

Yesterday, the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals heard oral argument in an appeal of a lower court order placing a nationwide hold on the revised version of President Trump’s Executive Order banning most travel from six majority-Muslim nations:

WASHINGTON — Skeptical federal judges peppered a government lawyer on Monday with questions about how much weight to give President Trump’s campaign statements calling for a “Muslim ban” as they assess the constitutionality of his revised travel ban.

The two-hour argument, before a 13-judge panel of the federal appeals court in Richmond, Va., was the first appellate test of Mr. Trump’s revised executive order limiting travel from six predominantly Muslim countries.

By the end of the argument, the judges appeared divided into two camps.

Some seemed prepared to look behind the face of the revised order to take account of Mr. Trump’s statements, and several suggested the remarks could doom the order. Others, though, said the law did not permit judges to second-guess a president’s national security assessments, indicating that they were prepared to uphold the order.

Groups challenging the order have said Mr. Trump’s statements concerning Muslims show that the revised order is the product of religious hostility. Such discrimination, they add, violates the First Amendment’s ban on government establishment of religion.

Judge Robert B. King suggested that judges could not ignore Mr. Trump’s statements and motives. “He’s never repudiated what he said about the Muslim ban,” Judge King said of the president.

But Judge Paul V. Niemeyer said Mr. Trump’s official actions should not be assessed based on his earlier statements. “Can we look at his college speeches?” Judge Niemeyer asked. “How about his speeches to businessmen 20 years ago?”

Jeffrey B. Wall, the acting United States solicitor general, said the court should not look behind the revised executive order to assess Mr. Trump’s motives. Most of Mr. Trump’s statements were made before he took the oath of office, formed a government and took advice from cabinet officials. “Candidates talk about things on the campaign trail all the time,” Mr. Wall said.

He added that the order concerned national security, an area in which courts should be reluctant to second-guess the executive branch.

“This is not a Muslim ban,” Mr. Wall said. “It has nothing to do with religion. Its operation has nothing to do with religion.”

But Judge Pamela A. Harris said that even if the order was neutral on its face, “it has a disparate impact on Muslims.”

Judge Barbara Milano Keenan said the order was very broad. “You’re talking about 82 million people,” she said. “There has to be something about those people’s nationality that renders them suspect.”

Judge Keenan pressed Mr. Wall about the limits of his position. Suppose, she said, that a candidate had said daily that he would ban Muslims on his first day in office because “they’re bad people.”

“Do you really mean we can’t consider the statements?” she asked.

Mr. Wall said there might be reason to do so if the situation were that extreme.

Judge Dennis W. Shedd urged Mr. Wall to be careful about his concessions. “You’re cracking that door,” Judge Shedd said.

Mr. Wall responded, “We think the door is shut.”

But Judge Shedd remained wary. “You just opened it,” he said.

Omar C. Jadwat, a lawyer with the American Civil Liberties Union representing people and groups challenging the order, said the volume and specificity of the comments from Mr. Trump and his advisers could not be ignored. He was repeatedly pressed by Judge Niemeyer on whether the order was problematic on its own.

“You just don’t want to answer the question of whether this order on its face is legitimate,” Judge Niemeyer said.

Judge King said the two sides were separated by a wide gulf on the central question in the case: that of whether to interpret the order in isolation or in the context of the various statements. “That’s where you all are like ships in the night,” Judge King told Mr. Jadwat. “That’s the most important issue in the whole case.”

Lyle Denniston comments:

The hearing appeared divided almost as if it were two separate hearings. In the first hour, government lawyer Jeffrey B. Wall was on the defensive for much of the time, but then, the second hour put the other lawyer – Omar C. Jadwat of the American Civil Liberties Union lawyer – in the same challenged posture.

If there was a difference, it was that more of the judges joined in confronting Wall than the few who tested Jadwat, although there was no difference in the intensity in either part of the questioning.

The questioning of Wall focused mostly on what President Trump’s purpose was in issuing the revised version of his executive order after the first had been blocked by the courts. And, rather than focus exclusively on the wording of the revised order, as Wall had tried to persuade the judges to do, the jurists kept quoting Trump as a candidate and then as the serving president in describing what this initiative was all about.

The repeated inquiry from the bench was whether Trump’s anti-Muslim comments during the campaign took away, or at least put into serious question, the legitimacy of his immigration restrictions.

Wall sought to portray what Trump has said since actually taking the oath of office and beginning to govern as more “ambiguous” than his campaign rhetoric, and worked hard to try to convince the judges that they had a duty to be more tolerant of what the head of an equal branch of government had said about actual policy.

The questioning of Jadwat aimed mostly at how far back in Trump’s pre-presidential past it was proper to look to find his motive when he, as president, started taking action on immigration.

And the judges confronting the ACLU lawyer tried to compel him to say, precisely, whether Trump would ever be able to take action on immigration policy without risking repeated court battles over what his real intentions were.

At one point, the probing of Jadwat’s argument came close to the absurd when he was asked if it would make a difference, to the challengers, if Trump were to publicly say he was sorry for his anti-Muslim remarks, whether it would make a difference how often he apologized, and whether it would make a difference if he seemed sincere or insincere in his apologies.

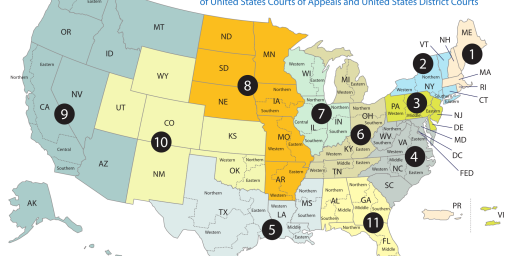

The unusual thing about this case is that the initial appeal is being considered by the full bench of active Judges on the Fourth Circuit, minus one Judge who did not participate in yesterday’s hearing and who will not be involved in deliberations, rather than the traditional three-judge panel. This is something that is permitted by the Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure and the local rules of the Fourth Circuit, but which generally only happens in rare circumstances at the discretion of the Judges and comes about after either a request for such an expedited procedure from the parties or, in extraordinary cases. At its most practical level, this means that the case would head right for the Supreme Court after the Circuit Court issues its decision rather than the possibility that the losing party from a panel decision would seek en banc review of a panel decision before the full Circuit Court. In any case, it’s unclear just what kind of impact this change in procedure will have on the outcome of the case, although it is worth noting that the current makeup of the Fourth Circuit is dominated by Judges appointed by either President Clinton or President Obama, and includes only five Judges who were appointed by either President George H.W. Bush or President George W. Bush. The decision of the Circuit as a whole will depend, as it does in the case of panel decisions, on which side of a majority of the Judges come down, so you can draw your own conclusion from those facts.

As I’ve said numerous times before, isn’t always advisable to try to make predictions about how a Court will decide a case based on oral argument. That being said, and based on the descriptions of the oral argument, it seems clear that the majority of the Judges were far more skeptical of the arguments being presented by Justice Department lawyers in defense of the Executive Order than they were with regard to the attorneys from Hawaii challenging it. In the later case, there seemed to be much skepticism about both the evidentiary basis for singling out the residents of the six nation covered by the ban as opposed to other Muslim nations such as Saudi Araba, Egypt, and Pakistan, which actually been the sources for terrorists that have carried out attack in the United States and against American properties and interests abroad and the true intent behind the law.The first issue is one that proved to be fatal to the first draft of the President’s ban during the arguments earlier this year in the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, and the second issue focused on the question of the extent to which statements by the President and his supporters regarding a ban on Muslim immigration during the Presidential campaign and prior to Inauguration Day should be taken into account in determining the intent behind the statute. In both cases, the Justices Departments arguments seemed to me to be rather weak and the Judge’s responses to the answers regarding those questions seem to indicate their skepticism regarding the government’s argument. The questioning for the attorneys for Hawaii and the other parties contesting the Executive Order largely seemed to focus on the issue to the extent of how far a Court can legitimately look at statements a President or legislator makes on the campaign trail before taking office to determine the intent behind a statute or action. This suggests that they are mindful of the danger of taking everything a politician says at face value and the necessity to stick to the four corners of a law or Executive Order unless the facts require one to look at the outside record to learn more about intent. Previous courts that have looked at the Trump travel ban orders have found that the comments from the President when he was a candidate, and from advisers such as former New York City Mayor Rudy Giuliani, regarding the desire for a ban that specifically targeted Muslims rather than one that was intended to address real security threats. In nearly all those cases, the Judges have found that the evidence was overwhelming that the actual intent behind the order was to bar Muslims from entering the country rather than to address a specific security threat. If the Fourth Circuit agrees with that conclusion, then the outcome of this case should be self-evident.

Yesterday’s hearings come just about a week before a similar hearing will take place before the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals on Monday, May 15th. Unlike the case in the Fourth Circuit, this case will be heard before a three-judge panel that has yet to be named, meaning that any decision could be appealed to either the Supreme Court or the full Ninth Circuit after the panel decision is handed down. In both cases, it’s likely that whatever decision we get from the Circuit Courts will be appealed to the Supreme Court, and it could end up being the case that they both end up before the Justices at roughly the same time. Whether the Court accepts either or both cases remains to be seen, of course, but the fact that the decisions involve an important issue of national implications and implicates both Federal law and the Constitution would seem to make it more likely that the Court will be inclined to accept the case. Additionally, if it turns out that the Fourth and Ninth Circuits end up issuing contradictory decisions, then there will be a split in the Circuits that makes it even more likely that the Court will accept the case(s) for appeal. In the case of a split, however, the travel ban would remain in effect since we would still have a District Court nationwide injunction in place as long as one of the cases ends up being decided in favor of the parties challenging the ban. The only thing that could end that bar on enforcement would be an order from both Circuit Courts, or from the Supreme Court, lifting the injunction. As for the timing of all this, there’s’ no way of telling when to expect decisions in either case, although it is worth noting that both the Fourth and Ninth Circuits agreed to what amounts to expedited treatment of the respective cases before them, so that suggests they’ll be relatively quick in handing down a decision.

A written transcript of yesterday’s hearing doesn’t appear to be available yet, but here is the audio from yesterday’s hearing:

It’s also worth noting that the hearing in the Ninth Circuit will once again be live-streamed. I’ll post details about that at some point before Monday’s hearing.

It’s not a Muslim ban – he totally deleted that promise from his campaign website this week.

Trump claimed that he needed 90 days to develop a security plan.

He has been in office for 109 days.

So where is this plan of his? If it was so damned necessary, then why is there no plan? Why aren’t his devoted followers demanding this critically important plan?

Liberal logic: “The true intent of this order is to ban Muslims. Our proof is that there are lots of Muslims in Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Pakistan who aren’t banned by this order.”

@Gavrilo:

Go rob a bank, then tell the court that you’re not a bank robber because you haven’t robbed every bank in town.

(Yeah, that argument will go over very well…)

@Pch101:

That’s a really stupid analogy.

@Gavrilo:

No, you’re an idiot to believe that an Islamophobe isn’t one because he hasn’t targeted everyone equally.

@Gavrilo:

That’s because Don the Con has business interests in most of the countries not banned.

But don’t listen to me, listen to the comb-over; here he is speaking about himself in the third-person:

I guess Dumb Don still hasn’t figured it out? He said he would have a plan to eliminate ISIS in 30 days.

Of course he says a lot of things and delivers nothing. Like you, fanboy.

I’m probably wrong but I remember reading somewhere (no reference) that some of the countries Trump wants to ban were originally on a list promulgated in the Obama administration because they were essentially failed states and there was no way to prove anyone carrying a passport from one of them was actually a citizen of or originally from one of them. If Trump had gone with that premise, dropped Iran from the list and added other countries from around the world that are in chaos and not Muslim (El Salvador) the ban may have been successful. Since that didn’t happen and all are Muslim of course it’s going to sink.

Breaking news: Trump has fired James Comey.

@Mr. Prosser:

That happened six years ago in response to a specific incident, and actions were taken in response to that incident. So those problems have already been addressed, and there was nothing for Trump to do — he may as well go on about Pearl Harbor and the Alamo.

In any case, nothing would have prevented Trump from ordering Homeland Security to issue some sort of report that addressed any alleged security vulnerabilities and provided a list of recommendations. But it should be obvious that there is no interest in fact finding.

Marty Leaderman point out something that went on in that hearing that could easily be the basis for the ultimate SCOTUS opinion – that the order itself, on its face, didn’t comply with the statute.

I think the Ban is doomed if Lyle Denniston is correct that “The questioning of Jadwat aimed mostly at how far back in Trump’s pre-presidential past it was proper to look to find his motive when he, as president, started taking action on immigration.” Wherever the line is, the question is not how far back but how germane Trump’s comments were to the specific order he executed. Judge Niemeyer seemed to defend the Order by arguing whether we can also “look at his college speeches? [and…] his speeches to businessmen 20 years ago?” Speeches like that would not have been about a Travel/Muslim Ban that he would specifically order upon becoming president years later. Speeches made on the campaign trail specifically for what he would order upon becoming president are way different and far more germane. #movementtowardthemiddle