HARD CASES MAKE GOOD LAW

Stephen Pollard explains how the Saddam Hussein capture caused him to rethink his position on capital punishment in a Telegraph piece entitled, “This is the week I changed my mind about hanging.”

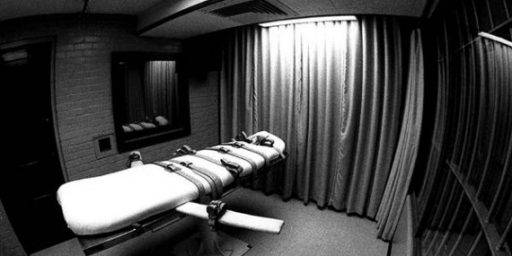

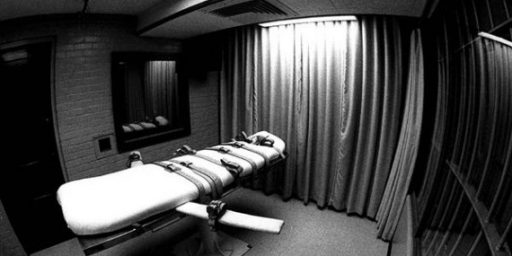

All my adult life I have opposed the death penalty. My reasons are standard, shared, I am sure, by the vast majority of those who oppose capital punishment. Of all of them, one stands out: better that 99 guilty men should go free than that one innocent man should be killed. That is, of course, a practical rather than a moral objection, but I have also had a principled objection to the idea of the state taking a life when it sees fit. War, certainly, presents a different circumstance, when there is simply no choice but for the state to kill in order to survive. But it is impossible to imagine how, in response to criminal behaviour, life imprisonment rather than execution would put at risk a country’s very existence.

***

Either capital punishment is immoral or it isn’t. By refusing to condemn any potential execution of Saddam, Messrs Blair and Straw and the others who have fallen into line behind them are, from their perspective on capital punishment, supporting a grotesquely immoral act. They are also exposing the deep flaws in their opposition to the death penalty at home. If it is wrong to execute Ian Huntley, it is wrong to execute Saddam. But that works in reverse, too. If, as the Prime Minister and Foreign Secretary appear to believe, it is morally acceptable to kill Saddam, how can it be any less so to kill Ian Huntley? It is a perverted moral calculus which holds that murdering two children is somehow more acceptable than murdering 300,000.

I have never been an absolutist in my opposition to ending human life. Since I accept that there are times when it is right to kill, in the last week I have had to ask myself an unsettling question: when could there be a clearer-cut example of living, breathing evil, and when could the extermination of that evil be more justified? As I watched the wonderful pictures of Saddam’s humiliation, I could not – nor can I still – think of a single reason why he should not be executed. I am left with only one response, which is that Saddam should indeed be put to death – after due process.

Much as I have tried to escape this conclusion, I cannot: there are no sensible grounds on which one can argue that it is morally right to execute Saddam but not Ian Huntley. Anyone who accepts that Saddam should be killed must also accept the case for capital punishment more generally. We can argue about details – to which forms of murder it should apply, and in what circumstances – but the principle is clear. Accept the moral validity of executing Saddam and you must accept it for executing Huntley – and, indeed, anyone convicted of cold-blooded and deliberate murder.

The imprisonment of Saddam has made me realise that, far from opposing the death penalty, I can see no moral alternative to it. As for the idea that it is better that 99 guilty men go free than one innocent man is hanged, the response of one visiting member of the Chinese judiciary to that statement is perhaps the most pertinent observation: “Better for whom?”

(Hat tip: Glenn Reynolds)