Natural Monopolies

Tim Wu has an excellent article about how the free-wheeling, free-market style of the Internet has led, for the most part, to natural monopolies.

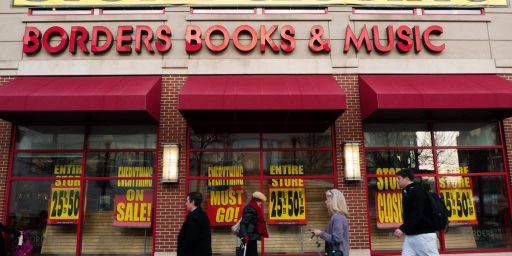

The Internet has long been held up as a model for what the free market is supposed to look like—competition in its purest form. So why does it look increasingly like a Monopoly board? Most of the major sectors today are controlled by one dominant company or an oligopoly. Google “owns” search; Facebook, social networking; eBay rules auctions; Apple dominates online content delivery; Amazon, retail; and so on.

There are digital Kashmirs, disputed territories that remain anyone’s game, like digital publishing. But the dominions of major firms have enjoyed surprisingly secure borders over the last five years, their core markets secure. Microsoft’s Bing, launched last year by a giant with $40 billion in cash on hand, has captured a mere 3.25% of query volume (Google retains 83%). Still, no one expects Google Buzz to seriously encroach on Facebook’s market, or, for that matter, Skype to take over from Twitter. Though the border incursions do keep dominant firms on their toes, they have largely foundered as business ventures.

The rise of the app (a dedicated program that runs on a mobile device or Facebook) may seem to challenge the neat sorting of functions among a handful of firms, but even this development is part of the larger trend. To stay alive, all apps must secure a place on a monopolist’s platform, thus strengthening the monopolist’s market dominance.

Today’s Internet borders will probably change eventually, especially as new markets appear. But it’s hard to avoid the conclusion that we are living in an age of large information monopolies. Could it be that the free market on the Internet actually tends toward monopolies? Could it even be that demand, of all things, is actually winnowing the online free market—that Americans, so diverse and individualistic, actually love these monopolies?

I think he’s confusing “natural” with “carefully crafted” Google, eBay, and Facebook hold the positions they do by design, not by happenstance.

I’m using “natural” in the sense of “product of the free market” rather than “product of government.” I agree that the companies themselves have pretty carefully crafted their niches.

“Could it be that the free market on the Internet actually tends toward monopolies?”

I wonder why he limits the question to the internet?

I agree that Google’s dominance in search is natural, and might qualify as a natural monopoly. Their incomplete share (72% of search in 2010) tempers that, as does their interchangeability (quality issues aside).

I think the danger here, the set-up, is to use the natural monopoly in internet services to make a sloppy argument that therefore “the internet” is made up of natural monopolies, and cable company packet preference is no big.

That would be a really bad argument, because “net neutrality” is in fact what keeps Google’s monopoly natural.

BTW, a number of apps do not rely on monopoly or single-source platforms. Android and HTML5 apps qualify qualify.

This is kind of an interesting notion. “Traditional” monopolies limited choice and competition. If own guy owned all the steel mills, that’s where you got your steel from, period. But I can still use Bing, which is good enough for most purposes. Most of us simply choose not to, though. And that’s not to mention both Google and Bing are free to use. The steel mill guy can charge whatever he wants.

So what are the negatives? And where is the boundary between the traditional monopolies and these Internet-based monopolies? For example, what if your OS prevented you from using certain browsers? Or what if your ISP limited your bandwidth to a certain website?

“Could it be that the free market on the Internet actually tends toward monopolies? ”

Could it be that the free market in general actually tends toward monopolies? Isn’t that why we saw the rise of the trust-busters (even amongst Republicans), and anti-monopolist laws?

Is a “free market” ever a stable end point without government regulation?

2 points.

1. in the cases of facebook, twitter, windows and so on, there is something called a band wagon effect. That is, that as more people use it, the value of using the product increases.So these kinds o products have a tendency to lead to monopolies.

2. A differentiation has to be made between the number of players in a market and the contestability of said market. It is possible to have an industry with only one firm, but still be contestable because new firms can easily enter the market and the threat of doing so keeps the dominant player in line. The second the dominant firm messes up or tries to raise prices, a new firms jumps in. I think the tech industry is indeed contestable and this has forced each firm to constantly be improving and expanding their respective products. Does anyone think Google has not been invating or they have extorted monopoly prices out of their customers? The second Google stops being the best search engine, some new firm will put them out of business. Remember when Altavista used to be the best search engine? I don’t think having dominant firms is a bad thing in of itself as long as they are exposed to competition.

Tano,

“Could it be that the free market in general actually tends toward monopolies?”

As alluded to in my first post, this only happens in either bandwagon effect types of products or in cases where the industry is very capital intensive and economies of scale continue to be posative through the entire size of the market. In the latter case industry cosalidation tends to occur.

But this does not happen in most industries. There are countless number of food establishments for existance and there is no government body regulating that industry with regard to how many firsm there are. Its just natural.

But also, see my first comment. Contestibility is more important than the number of firms. If a market is the prior, then a monopoly firm has little to no pricing power.

Google is a particularly poor example, it seems to me, because unlike other market victors (their not natural monopolists in the real sense as Dave Schuler points out) there are comparatively few barriers to exit. Alternatives are easily accessible and there’s no real penalty for switching. I can start using Yahoo or Bing at any time and would not be at all hindered by the fact that 70% use Google. On the other hand, if I use OpenOffice instead of MS Office, I am at a disadvantage by the fact that most people are using docs formatted in MS Office’s format. Right now, Google’s marketshare in terms of search engines and web tools seems to be pretty hard won. They have inertia on their side in that people won’t change search engines unless Google really drops the ball, but they can’t drop the ball and so far they haven’t.

Facebook is a slightly better example due to the bandwagon effect mentioned earlier. It simply does no good to be on a social network nobody else is on. eBay can really put the screws to sellers because they have the buyers (and they have the buyers because they have the sellers and it’s hard for anyone to compete with that loop). Amazon has economies of scale and to a lesser extent some of the advantages that eBay has.

“Could it be that the free market on the Internet actually tends toward monopolies?”

Considering how the internet operates, can we even fairly call it a “free market?” I mean, it’s not at all clear that Google has a monopoly on search. But we do know who has a monopoly on assigning IP blocks.