Originalism and the Declaration of Independence

The implications of modes of interpretation.

For a variety of reasons, some linked to recent SCOTUS decisions, some linked to events in daily life, and some linked to today’s date, I have been thinking about the problems that the Declaration of Independence creates for originalist interpretations of the founding documents of the United States. It all starts with how one looks at one of the most fundamental statements of the country’s founding:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.

Should we look at this statement for what it meant to Thomas Jefferson (and to those who read it) when he penned them in 1776? Or should we read it in a more universalistic, inclusive, and aspirational sense?

The key phrase is that “all men are created equal.”

I recall learning as a child that, as a general matter, when the male construction (e.g., “men” or “mankind” and the like) was used that it should be considered inclusive of all humans, male and female. This was before we moved, societally, to a more gender-neutral language. Such an interpretation allows for this phrase to be more inclusive than it sounds to our contemporary ears.*

It is quite clearly the case that Jefferson didn’t mean it that way, but we (largely) treat it as such.

Indeed, we treat this phrase like a sacred text, and with some good cause. Taken as aspirational philosophy it is practically a purpose statement of classical liberalism that treats humans as inherently equal with natural, equal rights. It is a statement (copied and sightly altered, I should note, from John Locke) that is requisite for the notion of self-government as it undercuts the notion of a special ruling class, i.e., aristocracy, and make way for democratic governance.

After all, if all people are equal, they should have an equal say in how they are governed.**

But, if the phrase is not inclusive, nor aspirational, then there are some pretty significant implications.

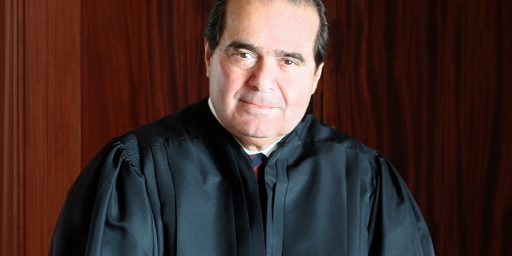

If one takes a textualist/originalist approach, as defined by the late Associate Justice Antonin Scalia, we should not worry about intent or aspiration, but we should (as he said in defining his approach in 2005) “give the text the meaning it had when it was adopted.”

That approach has some pretty significant implications. In fact, Scalia was quite dismissive of the general notion of treating documents with aspirational intent. As he stated in a speech in 1996:

What happens if the Constitution is, rather, a sort of an empty bottle that contains the aspirations of the society, just all sorts of wonderful aspirations, the precise content of which is quite indeterminate? Today, the Eighth Amendment ban against “cruel and unusual punishment” may mean the death penalty is ok, but tomorrow it won’t mean that. “Due process of law,” whatever that means will vary over time, the due process clauses in the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments meaning one thing today and something else tomorrow. We’re so in love with these abstractions, and, in the future, the Supreme Court shall decree for us what these abstractions mean. Now, if that’s what the Constitution is, sort of a list of aspirations, not a real law, then Marbury v. Madison is wrong.

So, what happens if we eschew an aspirational interpretation and try to understand the text as understood by those who wrote it and those who would have read it in 1776? We don’t need to wonder, since that was the precise logic of Chief Justice Taney in Dred Scott v. Sanford. He reached the conclusion that Blacks could not be citizens, and had to rights, using the text of the Declaration itself and some decidedly originalist/textualist logic (emphases mine).

It then proceeds to say: “We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights; that among them is life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness; that to secure these rights, Governments are instituted, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.”

The general words above quoted would seem to embrace the whole human family, and if they were used in a similar instrument at this day would be so understood. But it is too clear for dispute, that the enslaved African race were not intended to be included, and formed no part of the people who framed and adopted this declaration; for if the language, as understood in that day, would embrace them, the conduct of the distinguished men who framed the Declaration of Independence would have been utterly and flagrantly inconsistent with the principles they asserted; and instead of the sympathy of mankind, to which they so confidently appealed, they would have deserved and received universal rebuke and reprobation.

Yet the men who framed this declaration were great men–high in literary acquirements–high in their sense of honor, and incapable of asserting principles inconsistent with those on which they were acting. They perfectly understood the meaning of the language they used, and how it would be understood by others; and they knew that it would not in any part of the civilized world be supposed to embrace the negro race, which by common consent, had been excluded from civilized Governments and the family of nations, and doomed to slavery. They spoke and acted according to the then established doctrines and principles, and in the ordinary language of the day, and no one misunderstood them. The unhappy black race were separated from the white by indelible marks, and laws long before established, and were never thought of or spoken of except as property, and when the claims of the owner or the profit of the trader were supposed to need protection.

There is a lot to take in here, but the bottom line is that a reading of the Declaration in a non-aspirational, non-evolutionary way leads to some pretty grim conclusions.

A side note that is worth noting. Taney states that as of his writing in 1857 that the words of Jefferson would have been understood to be inclusive: “The general words above quoted would seem to embrace the whole human family, and if they were used in a similar instrument at this day would be so understood” (emphasis mine). This is stunning in a number of ways. It is basically an admission that sure, these days equal means equal, but it didn’t back then, so whaddya gonna do? The text is the text, after all. To me this is a blistering indictment of the very notion of originalism/textualism. And lest anyone accuse me of being unfair, I would ask the sincere question as to how Scalia’s logic is any significant deviation from Taney’s.

Of course, when Jefferson wrote the words “all men” what was in his mind? We know that he did not mean that Blacks were included. After all, at the time of the writing of the document, it is estimated that he owned between 165 and 225 slaves. We know that women were not considered equal to men. Indeed, we know that at the time voting rights, such as they were, had property restrictions on them.

The implications of such a reading are clear, and Taney’s originalist interpretation was sound if such logic is applied. In fact, one could argue (and I am not, to be clear) that Taney was correct in his interpretation and only the 13th and 14th Amendments corrected the situation. That is to say that the 13th banned slavery and the 14th made all former slaves into citizens and dictated equal protection under the law.

By the way, I get (to a degree, at least) the plain, clean logic of the following:

- Words mean what they mean when written.

- If meaning changes, change the law to add new words.

I think that the complexities of #2 are ignored when it comes to the actual human rights of large swaths of people (again, see Dred Scott).

For example, Scalia noted the following about woman’s suffrage in his 1996 speech linked above:

That the people thought the way I think is demonstrated by the Nineteenth Amendment, adopted in 1920. That is the amendment which guaranteed women the right to vote. As you know, there was a national campaign of “suffragettes” to get this constitutional amendment adopted, a very big deal to get a constitutional amendment adopted. Why? Why did they go through all that trouble?

If people then thought the way people think now, there would have been no need to add the Nineteenth Amendment to the Constitution. In 1920, there was an equal protection clause, right there in the Constitution, in the Fourteenth Amendment. As an abstract matter, what in the world could be a greater denial of equal protection of the laws in a representative democracy than denial of the electoral franchise–the right to vote–to women or to any other group of adult citizens with sound minds. The suffragettes could just come to the court and say, “This is a denial of equal protection,” and petition the U.S. Supreme Court to invalidate all state laws denying the franchise to women, to declare such laws to be violations of the Federal Constitution and therefore unconstitutional and null and void.

Why didn’t the suffragetters take this course of action? Because they didn’t think that way.

Equal protection could mean that everybody has to have the vote. It could mean that. It could mean a lot of things in the abstract. It could have meant that women must be sent into military combat, for example. It could have meant that we have to have unisex toilets in public buildings. But does it mean those things? Of course, it doesn’t mean those things. It could have meant all those things. But it just never did. That was not its understood meaning. And since that was not its meaning in 1871, it’s not its meaning today. The meaning doesn’t change.

The degree to which his example demonstrates that people used to think as Scalia did is a highly debatable question (or, at best, simplistic), but the passage above underscores his logic, and it is one that fits Taney’s: even if society evolves in what the words mean (such as “equal protection” or “all men are created equal”) it doesn’t matter: we are bound by the past. I understand that the notion of a fixed meaning is appealing, but I think such an endeavor is far too dismissive of the obviously evolutionary nature of language (not to mention society itself) and it also consigns whole classes of persons into second-class (or worse) status because the need for consistency trumps their humanity. Not to mention I am less willing to assume that it is possible to understand the original meaning as Scalia and his fellow adherents are willing to do. (See, for example, some of Samuel Alito’s tortured, at least in my view, attempts at making history and tradition fit his preferences. The notion that judges have the chops to draw well-researched historical conclusions is, quite frankly, a bit ridiculous).***

All of this is to say that if we don’t take an evolutionary, aspirational understanding of statements like “All men are created equal” then we are stuck in a past in which men were legally superior to women and Blacks were property. And if we are stuck in that past, then the Declaration is nothing to celebrate.

To be clear, I do want to celebrate the notion that human beings are equal and that they have rights due to their existence. But that requires recognizing that property ownership/wealth does not make one human better than another. It means recognizing that if one is male or female does not matter (nor, indeed, if one is trans or identifies in some other way). It doesn’t matter one’s ethnicity, race, or other factors. Humans are humans in all our manifest diversity, and either we have to take an evolutionary view on our founding, or we have to take a dim view of the slave-owners of the time and wash our hands of it and focus on something more contemporary.

Let’s face facts, if we are going to read the Declaration the way Jefferson’s contemporaries would have, then that’s a problem, is it not? But if we read it aspirationally that changes the meaning considerably.

I am firm in my belief (and in my normative preference) that “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness” should be a mission statement for the United States. Still, for it to be such, we have to read it aspirationally, else it is just a statement about the political power of white males with property who owned other human beings and thought that was morally justifiable. There is also the broad question of the definitions of “liberty” as well as the “pursuit of happiness.”

All of this does, at a minimum, raise questions of what it means to simplistically look to the Founding or to the Founders in constructing moral political stances in the now.

Indeed, I would argue that a patriotic interpretation requires an acknowledgment that we have evolved and should continue to seek to do so. But this requires a clear-eyed understanding of where we started, where we are, and how we got here (not to mention, considerations of where we yet might go).

*It is also a reminder that debates over gendered language are not all that new, and that we survived the question of whether using male-specific language should be seen as inclusive or not and we will survive whatever other travails of the ever-evolving usage of words have for us going forward. It is worth noting that the year after I was born, Neil Armstrong took “One small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind” and that was understood at the time to mean all of humanity. Or, on a more pop-culture level, two years before I was born, James Kirk was boldly going where “no man has gone before” but the year after I started college, Jean-Luc Picard was going “where no one has gone before.”

**This raises a huge number of questions about democratic governance that goes well beyond the scope of this post, but which informs a lot of what I write. It certainly has significant implications for certain versions of “we have a republic, not a democracy.”

***Of course, all of this really makes me wonder how “giv[ing] the text the meaning it had when it was adopted” means we have the current legal regime around guns that the Court has created, but that’s another discussion. It seems to me that if we are really, truly going to take that approach, then what Madison thought were “arms” and what we have today aren’t even the same thing. Why we should take an evolutionary approach of musket to AK-47, but not on human rights is, dare I say, a loaded topic.

Not to mention how we got from “A well regulated militia” to where we are now.

Captain Kirk boldly went “where no man had gone before.” A few years later Captain Picard went “where no one had gone before”, recognizing not only women, but aliens and an android. Things change. And treating originalism as a serious technique for Constitutional interpretation is a category error.

Textualism at least has some constraints. Originalism adds divining what the writers really meant and cherry picking history so that any preordained result can be rationalized. Pure Calvinball. But with the added claim that it’s the only valid method, so any contradictory precedent is, by definition, wrongly decided.

ETA – @OzarkHillbilly: A prime example. “We’re bound by the original text. Unless that’s inconvenient, then we’ll just divine that some words don’t count.”

Couldn’t one say the Declaration is an aspirational document while the Constitution is not?

Or does the fact the Declaration is aspirational, and America sprung from those aspirations, mean that by definition the Constitution must also be aspirational?

Great post, and some history I wasn’t aware of. The contradiction you note at the end of the last footnote is significant, too.

LOL. Why indulge in the conceit that this ‘originalism’ is the basis of their conclusions and not merely the cover for the outcome they want? Mainstream law has been long aware that Originalism is a stillborn judicial philosophy. Even it’s advocates (fringe dwellers) can’t figure out how make it workable.

It’s a trojan horse that provides a means to a predesired end and little else.

@gVOR08: “And treating originalism as a serious technique for Constitutional interpretation is a category error.”

Bingo!

I wholeheartedly agree with your analysis. The Declaration is the prime founding ethos of the nation, whereas the Constitution is an owner’s manual.

It is grimly amusing that you continue to employ logic and reason while the “originalists” or “textualists” are not so constrained. As gVORo8 rightly states, it is pure Calvinball. If conservatives have a majority on SCOTUS, then the Constitution is whatever they say it is. Calvinball power politics.

@OzarkHillbilly:

That part has tripped me up often.

It began to make sense when I started delving into ancient history. Many polities in that era, from city-states to empires, lacked a standing army, and required men to furnish their own gear and weapons when called to serve (mostly they were not paid either, ergo all the wartime looting).

But I don’t know whether that was the case in America’s early days. I know there were volunteer regiments in the civil war, and even as late as the Spanish-American War. Though my understanding is these were raised and equipped by wealthy men, with the intent that the government would incorporate them to the army and pay the bills from than on.

So, if it was necessary that people owned and carried firearms (single-shot flintlock rifles using lead munitions) in order they could form armies (militias) as the need arose, the need didn’t seem to last long. it certainly is not the case now.

@Mikey: I tend to be of the view that the constitution is at least evolutionary, if not aspirational.

“Equal protection under the law” means something different in 2022 than it did in 1868 and I don’t think we should be bound by the 1868 meaning.

A) The concept of language as simply a set of words with fixed definitions organized by grammatical rules is such a bad one. Ordinary language uses abstraction and implicature and irony and inference. That is why bots sound like bots–because you can program definitions and grammar but you can’t program implicature.

B) I’ve always thought that Scalia and all of the ‘originalists’ cling to the past because they think that guys who wrote ‘All men are created equal’ had the same types of prejudices as closed-minded bureaucratic conservatives who never left academia. Jefferson owned slaves and raped and whipped them, but he also was a man of curiosity and imagination. He wasn’t clinging to the 16th century when he thought of the natural world or pre-revolutionary France.

C) I think, despite all of the Opus Dei drapery of someone like Scalia, that this type of conservatism is far more modern and technocratic than any of the chaos and liberties the ideology is opposed to.

As a non-American with a long standing interest in American history in its wider context, a few words in the Declaration that often :

In other words, there are other unalienable Rights.

Might be worth seriously considering what those might be.

And the possibility that thy couldn’t agree at the time; or perhaps they were taken to be too “self evident” to need explication.

We can probably assume that Jefferson didn’t just run out of time or space to finish writing them out 🙂

Also, does Scalia think Luke 2:14 should be read as exclusive of women, or that women or anybody not a man is being aspirational in thinking that the angel is talking to all of them?

Of course as I type this my brain is making me remember that there is a huge translation issue with the Gospel in the 2nd century and that the phrase ‘good will towards men’ in Ancient Greek was mistake and should have been ‘good will towards those whom God favors’. And I think that this has pissed off a certain type of Catholic ever since who I guess we’re believes being a bit too aspirational with the New Testament.

Regardless–unless we are insane–we understand the angel’s use of the word ‘men’ as being inclusive of women. And the Founders would have as well.

And to think there was no episode where Captain James T. Kirk boldly beamed into the ladies’ room.

@Mikey:

Thank you for reminding me. Why the hell was Taney interpreting the Declaration, which has no legal standing?

@Kathy: That sounds like something Kirk would do.

Also, in terms of historic accuracy, Justice Taney was an egregious ass.

English and Scottish Law was well known to be ambiguous on the matter; the base justification for slavery was an argument from non-Christianity rather than race, IIRC.

The Knight Case judgement in 1777 expressly stated: “…the dominion assumed over this Negro, under the law of Jamaica, being unjust, could not be supported in this country to any extent…”

But as the Law was often a tool of the political and economically dominant, it is hardly surprising that it was never able to effectively interfere with the Slave Trade until after American Independence.

In Portugal, though the law, unlike in Britain, explicitly recognised slavery, it was not confined to Black Africans.

Neither were all Black Africans assumed to be slaves. Lisbon had a sizable population of free Black Afro-Portuguese for centuries.

And nor was slavery necessarily confined to Black and/or African persons.

The French sent Protestants as slaves to the galleys until the mid-18th century.

Portugal regularly enslaved Asians in the 17th and early 18th centuries.

Not to mention the Moorish trade in European slaves, which ran into millions of persons.

The key factor in the evolution of slavery in the late medieval to early modern period was religion not race, and centred on the Mediterranean and South East Europe, where all sides tended to regard “infidels” as legitimate targets.

And in any case, given that by 1857 abolition of slavery had become pretty general outside the USA and Brazil, Taney’s argument is even more anachronistic.

In short, Taney was not objectively analysing law, history, or even contemporary practice, but simply working up a barely plausible exculpation for a decision made on other grounds, that could persuade only those who wanted to be persuaded.

Which looks to me like good cause for casting a jaundiced eye over other examples of judicial motivated reasoning, and that Taney’s view of the Founders beliefs and their implications might similarly be an utter pile of nonsense.

@Modulo Myself: In their book Winner Take All Politicspolitical scientists Hacker and Pierson talk about “drift”. Drift is just that, drifting along with nothing being done. Our system makes it so hard to do anything major that drift is easy to accomplish. And people who are doing well under the status quo are happy with drift. They don’t want freedom extended to any out group. That don’t want any new regulation of their corporations. They don’t want any new taxes. They recognize what J. K. Galbraith said about strong unions and government being the only powers able to “countervail” big corporations. They’ve crippled unions and drift hobbles government.

Scalia, Kavanaugh, Gorsuch, Thomas, and Barrett are ideologues, but mostly they’re doing what their sponsors pay them to do. And Roberts. Their sponsors do have a glibertarian ideology, but mostly they’re just guarding their money. I think we flatter these Justicest by regarding them as anything but paid hacks.

Say what you will; Scalia certainly nailed that one.

@JohnSF: Chances are good that life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness were the only ones that applied to his argument. It’s an economy of expression, focusing of argument tactic.

What always struck me was how many of those places already had someone there. Often star-faring someones. I thought that most of them would probably be offended at the notion that “no one has been here before”. It’s a clumsy way to phrase things, whether it’s no one or no man.

@JohnSF:

Sam Alito: “Hold my beer…”

@Kathy:

“And to think there was no episode where Captain James T. Kirk boldly beamed into the ladies’ room.”

There was a Mad magazine parody where one of the other officers walked into a ladies room at that point.

Under the heading of Devil’s Advocate:

As I grasp Taney’s and Scalia’s problem, they address a view of the court as strictly limited to interpreting our owner’s manual and that’s not an altogether bad thing to a have. If We The People don’t like it we have the recourse of Amendments. Should we demand the least democratic, the least representative, branch of the government interpret us instead of our manual?

We blindfold Lady Justice and wonder why She’s ignorant.

@dazedandconfused:

Yes, we should.

The Constitution’s very first words are “We the People” not “This the Document.”

Note, Scalia did not actually believe the court was “strictly limited” to interpreting the Constitution in a manner divorced from the people’s values, interests, and priorities. Dissenting from Casey and arguing for the value of unborn ‘lives,’ Scalia admitted, “There is of course no way to determine that as a legal matter; it is in fact a value judgment.”

@DK:

I would say his ““There is of course no way to determine that as a legal matter;” says the opposite.

Ideally yes, the court would be wise, but they are a group who’ve been heavily trained in the narrow area of Owner’s Manual interpretation, not mechanical/electrical engineering. Can’t damn them overmuch for wishing to stick to their area of expertise.

@Kathy: In the past I have often noted that it was my feeling that the 2nd Amendment comes out of our frontier heritage. In 1776 a fair amount of the 13 colonies were in fact at the very edge of wilderness and as such, far off from any help. Settlements were quite remote and on their own if troubles* arose and so formed militias for self defense. At the time of the constitution the 2nd amendment as it is written made perfect sense, but makes very little sense now.

*”troubles” could mean anything from Indian raids to slave rebellions to the predations of organized banditry

@dazedandconfused:

@DK:

I agree we should, in large part because the fundamental rights of any group of people should not wait on the pleasure of the majority.

And there’s the Anti-Mitch Principle: if there is a remedy, it should be made us of even if other remedies exist. I mean here that if judicial review is a valid avenue for a remedy, then there’s no reason why a constitutional amendment should be preferable.

@JohnSF:

And unenumerated rights… Unfortunately the majority in the court only recognizes ones written down by the founders.

@OzarkHillbilly: Yes, the 2A could flow from our frontier heritage. Or from the recent revolution in which militias took part. Or from a dedication to self defense. Or maybe from a powerful gunsmiths lobby. Or from a belief the people should revolt now and again. But the history seems to show it was because Patrick Henry feared the feds would disarm his local militia, the VA slave patrols.

Originalism is a sham, a cover for doing whatever the powerful wish. Citizens United was a 2010 ruling; the first 230 years corporations were restricted, and suddenly they had personhood rights. Roe v Wade was the law for fifty years, and now pfft it’s gone. It is like arguing about the will of God; it is a device to shut up people who disagree. It is bullshit. Scalia was a lawyer, an advocate, and I mean that in the worst sense of those words.

Originalism is a version of “I’m not interpreting, I’m being objective”. Sadly, as Steven so ably demonstrates, there’s no such thing as being objective in these matters (There is such a thing as empiricism, that’s not the same, and it doesn’t help here very much.)

You see this in, for instance, Biblical interpretation as well. The “plain meaning” is venerated in some cases, even when it pretty clearly is meant to be metaphorical or poetic.

Gun control is an even better example than you mention because, in fact, the precedent is that for literal centuries, we allowed municipalities (I don’t think states did, but I’m not sure) to restrict access to guns. Dodge City being a prime example. So much for long-standing historical precedent, which they only care about very selectively.

I lost what respect I had for Scalia’s textual analysis when I heard that he was an adherent of the “Bacon wrote Shakespeare” theory. Utter lunacy. Exactly the sort of stupid thing only a smart person can do.

By the way, I think there’s a good chance that when Jefferson wrote “all men” he meant all men. Even the black ones that he owned. Jefferson knew slavery was bad, but it was a drug habit he couldn’t kick.

I have known quite a few people who smoke cigarettes and knew they should quit, but didn’t or couldn’t. They wouldn’t argue that it wasn’t bad, they just couldn’t/wouldn’t stop. I think slavery was like that for quite a few slaveholders.

I suspect that much of that polemic could be reduced if the “originalists/textualists” simply dropped the “textualist” bit and calling themselves only “originalists”

@Jay L Gischer:

And then they don’t even get the history right. Alito’s assertion that abortion isn’t rooted in US history and tradition is plainly false. During our colonial days and well into the 19th century, abortion rules were often governed by old common law that allowed pregnancies to be terminated until “quickening” (fetal movement).

Abortion restrictions did not become de rigeur until later in the 19th century. And at first, those restrictions were predicated on protecting women from botched abortion, not on protecting “potential life,” a personal religious test with zero constitutional basis, imposed by the Court’s radical extremist Catholic majority. The Catholic Church itself did not officially turn against abortion until the 1870s.

So in fact, the Roe/Casey standard of safe, legal pre-viability abortion has a longer history and tradition in the US (and the world) than does the current forced birth gobbledygook.

The Apartheid Court’s majority are not originalists nor textualists. They’re tyrannical, partisan hacks doing the bidding of a far right Republican minority. Re: the 2nd Amendment, they’re just making it up as they go along, as neither the text, intent, or historical application has ever until now meant allowing any nut to own and carry any firearm anywhere unrestricted and unregulated.

Alito, Thomas, Kavanaugh, Gorsuch, Barrett and Roberts are lying to us. They are without honor and should be ashamed of themselves.

Steven, I tire of the continued assertion that conservatives in general – and these Republicans in specific – are in any way bargaining in good faith.

“Originalism” is NOT some sort of objective intellectual framework And We Just Differ On Conclusions.

USSC “jurisprudence” from the moment Roberts was crowned has been simply Calvinball — they’re making it up as they go along. Clarence Thomas admitted it — his entire life is based on Owning The Libs, and in that way they work backwards from conclusions to achieve their desired results. It’s pure politics, and to think otherwise is actually gaslighting yourself.

Conservative “originalism” is simply a shell game in which current political preferences are made to appear part of The Original Meaning And Intent. Note the game: Who exactly gets to be the final arbiter of original? Magically, the very person who’s the conservative with the political position. I’m shocked to find there’s gambling in this casino!

Also, the wild, gaping falsehood in this Originalist nonsense: the assertion-without-proof that their definition is simply not subject to the rules of verification which apply to all historical works.

All these “originalist thinkers”… DISMISS every single elite’s ideas at the time because “That Guy Might Have Had Political Motives” and so ignore him, rinse and repeat every single human, and magically substitute their own beliefs via their own fictitious Smrt Guy On The Street. This strawman of course Would Have Supported everything conservatives want… and in this way originalist “thinkers” casually ignore the reams of historical documentation wildly contradicting [newspapers, primary source documents, etc] and showing that American public didn’t support those ideas. So stop carefully considering their vomitous effluent — they don’t care.

Originalism is really nothing more than a collection of Thomas Friedman’s fake cab driver stories.. written in legalese and dressed up in a historical costume. They haven’t transcended history — they’ve rejected reality and substituted their own beliefs.

Power? Sure. Accurate representation of humanity or remotely respectable? Not a chance.

An interesting perspective on the artificial construct called “originalism” – thank you.

One quibble – the 13th Amendment merely moved slavery to the prisons, a problem quickly rectified by industrious legislatures who created new crimes out of whole cloth to perpetuate the system.

Originalism is currently just another word for tyranny. Our forefathers were not originalists, as they were white, males seeking to break from a royal-corporatist ruling class in Great Britain. If they were originalists, they would have simply suffered and stayed under the thumb of a king and unchecked corporate influence. The majority of our American people have inherited the desire of their forefathers, in that they also seek to unravel tyranny. Now, we the majority seek to address the tyranny of a minority, which is hell bent on making most of us suffer their twisted visions and subjugating application of power.

For the Catholics on the Court: the Doctrine of Originalist Sin.

🙂

Even more at issue is the status of a standing army during peacetime. I mean the founders were pretty clear that one of the reasons for the 2nd is because they decided that a large standing army in times of peace is dangerous to liberty. Which is why they tried to limit the ability of the Federal government to find the army under the army clause (Article I. Section 8. Clause 12.2 ), which has been largely ignored since the war of 1812. No SCOTUS decision or hand ringing, we just plain ignore it. Not one of these originalists would dare tie the hands of congress to anything like a strict interpretation of that clause.

“Originalism”, is just the flip side of “The living constitution” in terms of BS arguments to arrive at your personal outcome to any given decision.

Decisions should balance the tension between individual liberty and interference with the rights of others that an individuals expression of liberty might cause. There is also the difference between what should be allowed in publics places and on private property. The court ruling on whether or not states and localities can regulate guns in public has been settled law since the 19th centu8ry and this SCOTUS just blew that up not even considering that the exercise of one right might lead to violating someone else’s rights. Also the abject deference this court extends to Christians who claim religious liberty opposed to just about any other religion is scandalous.

My $0.00

If there were an edit feature the third sentence would read “Which is why they tried to limit the ability of the Federal government to *fund* the army under the army clause.

That is all … Squelch

Dr. T, as always, a reasoned, well expressed and cognizant post. I appreciate the effort you continue to put into this, as well as the rational and well spoken comments from the group. It’s a lot to chew on today, but I really appreciate the thought and effort everyone’s put in to this. I just wish the rest of our society would be this invested in the future of the nation. Thanks to all of you.

@Tony W:

I almost made a comment about this, but ended up not doing so. These posts get long as it is.

@Kathy:

Yes, we should feel entitled to remedies but events have proven

what the SC giveth the SC can taketh away, and pretty much just cuz’ the feel like it.

@Jay L Gischer:

This actually fits Scalia perfectly if you’re aware that the Shakespeare authorship question was originally a part of the “The Tudor Prince” conspiracy theory that there was a secret heir to Elizabeth I, and that everything would have been better if they’d become king and ruled as an absolute monarch instead of the Stuarts coming in and messing everything up and letting England get all democratic