Should We Destroy The Smallpox Virus, Or Save It?

The last known case of smallpox happened in 1977. Is it time to destroy the virus?

World health authorities are once again confronted with the question of what should be done with the last known living examples of smallpox left on Earth:

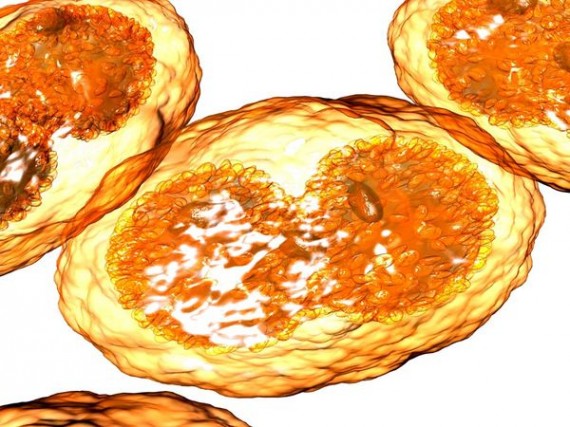

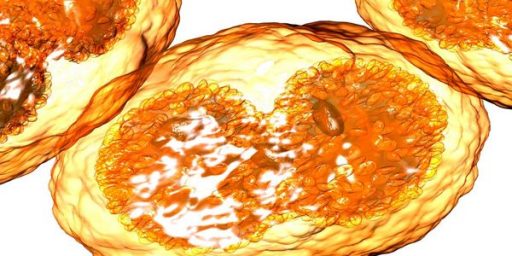

Smallpox was perhaps one of the most dangerous diseases on Earth. One variant of the disease has a 30% fatality rate; in Europe smallpox is believed to have claimed around 400,000 lives per year by the end of the 18th century, and worldwide an estimated 300 million people died of smallpox in the 20th century alone. The disease has gruesome physical symptoms—welts filled with opaque fluid that ooze and crust over, leaving survivors scarred with the remnants of its hallmark skin lesions and bumps.

This month the World Health Organization (WHO) will meet to decide whether or not to destroy the last living strains of the variola virus, which causes smallpox. Since the WHO declared the disease eradicated in 1979, the scientific community has debated whether or not to destroy live virus samples, which have been consolidated to laboratories in Russia and at the U. S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Atlanta. Small frozen test tubes preserve the surviving strains, and most were collected around the time of eradication, though some date to the early 1930s.

Inger Damon, who leads the poxvirus and rabies branch at the CDC, and her colleagues argue in an editorial in PLoS Pathogens today to save the virus from full extinction. According to Damon, retaining the live samples will allow researchers to delve into unanswered questions about the variola virus and to test better vaccines, diagnostics, and drugs. “There is more work to be done before the international community can be confident that it possesses sufficient protection against any future smallpox threats,” they write.

She notes that the live virus has already been used to find compounds that naturally fight smallpox and to test vaccine candidates with fewer side effects, like IMVAMUNE. “If we don’t have the virus, we won’t be able to test some of these compounds or test serum from vaccines again the virus itself,” says Damon.

Alex Berezow sees other reasons to keep the virus alive, just in case:

First, the world would have to trust Russia to destroy all of its smallpox. Russia is, to put it diplomatically, not a trustworthy partner. The former Soviet Union signed a 1972 treaty, called the Biological Weapons Convention, that banned biological weapons. After signing it, the Soviets increased production of those weapons. It wasn’t until 1992, under Russian President Boris Yeltsin, that the program actually came to an end. (Or, so they say.)

Considering that Russia sells weapons to murderous tyrants like Syria‘s Bashar al-Assad,maintains friendly relations with North Korea, and invades smaller, defenseless neighbors likeUkraine (while simultaneously denying that they are conducting an invasion), the notion that Russia might be lying about biological weapons research is not terribly far-fetched.

Second, the fate of the Soviet biological weapons is unknown. It is entirely possible that weapons, vials of smallpox, or unemployed scientists ended up in places like Iran.

Third, every once in a while, there is a smallpox scare from historical samples. What was thought to be a 135-year-old smallpox scab turned up in a museum in 2011. It ended up not being smallpox (but possibly a related virus known as Vaccinia). Still, the possibility of smallpox viruses surviving in old human tissue samples is a real enough threat. In an e-mail interview with RealClearScience, Dr. Inger Damon, the lead author of the PLoS Pathogensarticle, wrote, “The virus is highly stable when frozen; periodically the question of viable virus existing in corpses buried in the northern permafrost is posed, but remains unanswered.”

Fourth, as the op-ed authors indicate, there is still much basic research to be done. For instance, it is unknown why smallpox only infects humans. Comparing smallpox to other related viruses will help enhance our understanding of virology. Additionally, further research will improve smallpox diagnostics and vaccines, in the event that something unthinkable occurs.

For these reasons, smallpox stockpiles should not be destroyed for the foreseeable future.

This debate has cropped up every now and then in the years since the disease was officially declared eradicated in 1980 after what can only be called one of the greatest public health campaigns in human history. In the course of a relatively short period of time, the disease went from one that would infect millions, causing serious complications and death to one in which the last known naturally occurring case occurred in 67 years ago. At that point, the only known live samples of the virus were at the Centers for Disease Control and in the Soviet Union. In 1986, the World Health Organization first recommended that all remaining samples be destroyed, but the scheduled 1993 destruction was delayed until 1999 and then again further delayed. On each of these occasions, the arguments have been essentially the same. On the one side, there are those like Damon and Berezow who argue in favor of the research and security reasons in favor of keeping at least some sample of the virus on hand in case a future outbreak from some previously unknown source were to occur. On the other side are those who argue that there is no value, and tremendous danger in keeping alive a virus that could fall into the wrong hands. the mo

In the end, both sides make compelling arguments. However, it strikes me that Damon and Berezow have the stronger argument here. At the moment, keeping this virus alive is the only way we have to ensure that we’d at least have the building blocks for a vaccine should the need for one arise in the future. Obviously, there are concerns about how secure those virus samples actually are that should be addressed, and I can’t say that I necessarily trust the Russians with something like this given the danger that Russian scientists might trade information for money as we’ve worried they would over nuclear technology. That being said, though, until we develop some other method of storing the critical information the virus contains, we ought to keep it alive. Hopefully, we’ll never have to use it.

H/T: Andrew Sullivan

As Star Trek: The Voyage Home showed us, extinction (no matter how well intended in this case) can really come back to bite us in the ass when you least expect it. We have no guarantee that in the future, some superbug won’t arise that we need this sample for comparison and study. Yes, it is a danger…. but so are aging nuclear weapons we keep around “just in case”.

Here, it is better to err on the side of caution. Feel free to triple security if it helps you sleep at night rather then make a mistake you can’t take back.

Yeah, I was uncertain going in, but the “keep it” arguments are pretty compelling. Putin has decisively abandoned any pretense of democracy and Russia is on its way to absolute dictatorship. There’s no trusting the Russians.

We need it as defense against aliens.

Also, why bother? What are the costs for keeping it around?

If I was certain it could be kept safely I would say yes but since I’m not convinced I am uncertain.

Just want to point out that worrying about what the Russians might do with it is a really stupid reason for keeping it around. We no longer vaccinate against smallpox. We no longer have SP vaccine, and even if we did the chances are it would not work. It would have to be made, and it would have to be made from the latest strain. If the Russians were to “weaponize” it, you can be sure ours would not match up to it. So we would have to wait for a few to die before we had a strain to work with. Or else steal their vaccine. Either way, it takes time.

That said, I favor keeping it for the science. There is no telling what we have not yet learned from it, and once we destroy it that opportunity is gone forever.

There is more risk of the disease reemerging from frozen or otherwise preserved tissue than there is of it being released from the CDC (I don’t know about the Russians, nor trust them). Destroying the samples would be foolish.

@michael reynolds: true, and just in case the Indians ever get any ideas!

It has been sequenced. Destroying any virus particles will leave the information to reconstruct it intact. This is a question largely made moot by technology.

I know I’m a little late on the comments here, but I just happened to read that smallpox is the *only* disease we have eradicated. And there’s not likely to be any more, with the anti-vaxxer movement.

@Franklin:

We were getting pretty close with polio, but persistence in Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Nigeria and recent outbreaks in Somalia, and Syria have hampered the effort. Basically, it’s really tough to fight disease in areas of extreme poverty and/or nonfunctioning government. I think we will eventually manage to get rid of that one too, though.

Also, we did get rid of rinderpest too, but that only affected livestock.