Supreme Court Reaffirms Defendant’s Right To Decide Whether Or Not To Plead Guilty

Earlier this week, the Supreme Court handed down a decision that reaffirmed a principle that should be axiomatic, namely the idea that a Defendant has the sole authority to decide whether or not to concede guilt.

Although it got less notice than the decisions dealing with sports gambling and the Fourth Amendment, the Supreme Court handed down another important decision on Monday that reaffirmed what seems as though it should be an axiomatic idea, the notion that a criminal defendant has the ultimate authority decide whether or not to plead guilty:

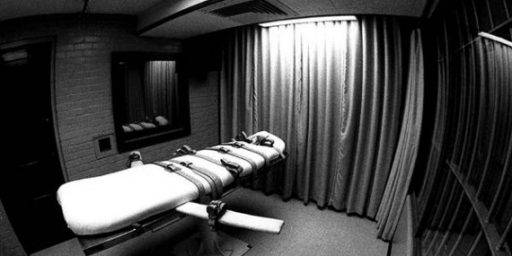

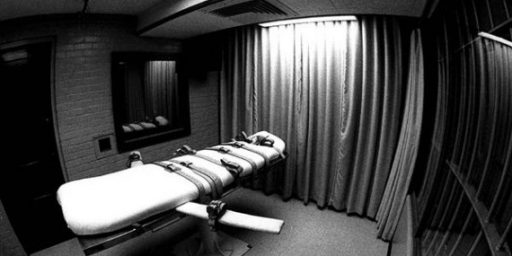

The death penalty case concerned Robert McCoy, who was sentenced to death in Louisiana after his lawyer told the jury Mr. McCoy had committed a triple murder.

Mr. McCoy had insisted that he was innocent and had told his lawyer, Larry English, that he wanted to clear his name. But Mr. English pursued a different strategy in the 2011 trial, hoping that a candid acknowledgment of his client’s actions would earn him credibility during the trial’s sentencing phase.

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, writing for the majority in the 6-to-3 decision, said Mr. English was not entitled to disregard his client’s instructions. His disloyalty, she wrote, required a new trial.

“We hold that a defendant has the right to insist that counsel refrain from admitting guilt, even when counsel’s experienced-based view is that confessing guilt offers the defendant the best chance to avoid the death penalty,” Justice Ginsburg wrote. Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. and Justices Anthony M. Kennedy, Stephen G. Breyer, Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan joined her opinion.

In dissent, Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr. wrote that Mr. English had not conceded his client’s guilt but only that he had killed his victims. Mr. English continued to maintain that his client was not guilty, Justice Alito wrote, by arguing that he lacked the intent required to make him guilty of first-degree murder. Justices Clarence Thomas and Neil M. Gorsuch joined Justice Alito’s dissent.

Mr. McCoy was convicted of the 2008 killings of Christine Colston Young, Willie Young and Gregory Colston, who were the mother, stepfather and son of Mr. McCoy’s estranged wife. There was substantial evidence that he had committed the crimes and some reason to think that Mr. McCoy’s belief in his innocence was delusional.

But there was no dispute about Mr. McCoy’s instruction to Mr. English. He was adamant that he was innocent and that others had carried out the murders. Mr. English disagreed.

During his opening statement at the trial, Mr. English used the strategy he had promised. “I’m telling you,” he told the jury, “Mr. McCoy committed these crimes.”

In the end, Mr. English’s trial strategy failed. Mr. McCoy was convicted and sentenced to death. He appealed to the Louisiana Supreme Court, saying his lawyer had betrayed him. The court ruled against him.

New York Times Supreme Court reporter Adam Liptak had previewed the case at the beginning of the Court’s term, and noted that many of the Justices seemed skeptical of the arguments from the attorneys for Louisiana during oral argument in January:

The Supreme Court on Wednesday seemed inclined to side with Robert McCoy, who was sentenced to death in Louisiana after his own lawyer told the jury he was guilty of a triple murder.

Mr. McCoy had insisted that he was innocent and had told his lawyer, Larry English, that he wanted to clear his name. But Mr. English pursued a different strategy, hoping that a candid acknowledgment of his client’s guilt would earn him credibility during the trial’s sentencing phase.

Several justices said a decision as fundamental as admitting guilt in a capital case belonged to the client rather than the lawyer.

Justice Neil M. Gorsuch invoked the text of the Sixth Amendment, which guarantees a right to “the assistance of counsel.”

“Can we even call it assistance of counsel?” he asked, referring to Mr. English’s conduct. “Is that what it is when a lawyer overrides that person’s wishes?”

Justice Elena Kagan said Mr. English may have been an effective lawyer but nonetheless one who had betrayed his client.

“There’s nothing wrong with what this lawyer did, if the goal is avoiding the death penalty,” she said. “The problem that this case presents is something different. It’s the lawyer’s substitution of his goal of avoiding the death penalty for the client’s goal.”

Mr. McCoy, she said, was entitled to take his chances if his “paramount goal” was to insist that he had not committed the murders.

Seth P. Waxman, a lawyer for Mr. McCoy, said the Constitution guaranteed him the right to direct at least the most fundamental aspect of his defense.

“When a defendant maintains his innocence and insists on testing the prosecution on its burden of proof,” Mr. Waxman said, “the Constitution prohibits a trial court from permitting the defendant’s own lawyer, over the defendant’s objection, to tell the jury that he is guilty.”

But Elizabeth Murrill, Louisiana’s solicitor general, said lawyers should be able to ignore their client’s wishes in some cases.

“In a narrow class of death penalty cases,” she said, “counsel sometimes might be required to override his client on a trial strategy when the strategy that the client wants counsel to pursue is a futile charade and requires him to defeat both their objectives of defeating the death penalty.

Previously, the Supreme Court had ruled in a 2004 case called Florida v. Nixon that held that defense attorneys did not necessarily need to obtain their client’s express consent before pursuing a strategy that concedes their guilt to the underlying charges in a death penalty with the idea that doing so would be of benefit in the sentencing phase of the proceedings. That case, though, did not address the situation in this case where a client was expressly objecting to the idea of conceding guilt to the underlying charges but the attorney decides that it would be strategically advantageous to do so anyway in the hope that they could save their client from the death penalty. As Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg made clear in her opinion for a 6-3 Court majority, this violates the notions of client autonomy at the core of the Sixth and Seventh Amendments to the Constitution:

Autonomy to decide that the objective of the defense is to assert innocence belongs in this latter category [of decisions that ought to be within the prerogative of the Defendant. Just as a defendant may steadfastly refuse to plead guilty in the face of overwhelming evidence against her, or reject the assistance of legal counsel despite the defendant’s own inexperience and lack of profes sional qualifications, so may she insist on maintaining her innocence at the guilt phase of a capital trial. These are not strategic choices about how best to achieve a client’s objectives; they are choices about what the client’s objectives in fact are.

Counsel may reasonably assess a concession of guilt as best suited to avoiding the death penalty, as English did in this case. But the client may not share that objective. He may wish to avoid, above all else, the opprobrium that comes with admitting he killed family members. Or he may hold life in prison not worth living and prefer to risk death for any hope, however small, of exoneration. When a client expressly asserts that the objective of “his defence” is to maintain innocence of the charged criminal acts, his lawyer must abide by that objective and may not override it by conceding guilt. Preserving for the defendant the ability to decide whether to maintain his innocence should not displace counsel’s, or the court’s, respective trial management roles.

Amy Howe analyzes the decision for SCOTUSBlog:

The majority acknowledged that English found himself “in a difficult position: he had an unruly client and faced a strong government case.” And it was reasonable for him to believe that he should try to avoid a death sentence for McCoy. But, the majority explained, even when a defendant is represented by an attorney, he does not give up all control over his case to the attorney. A criminal defendant’s lawyer may be responsible for what the court described as “trial management” – for example, what evidence to object to and what arguments to pursue – but the defendant himself has the sole right to make some decisions, such as whether to plead guilty or to waive the right to a jury trial. The decision to maintain one’s innocence, the court reasoned, falls within the category of decisions reserved for the defendant: If the defendant tells his attorney that “the objective of ‘his defence’ is to maintain innocence of the charged criminal acts,” the court continued, the attorney must follow that instruction and cannot “override it by conceding guilt.” This means, the majority concluded, that once English knew that McCoy objected to his proposed strategy of admitting McCoy’s guilt to the jury, it was not English’s place to override McCoy’s objection.

The majority went on to rule that this violation of McCoy’s rights falls within the category of errors known as “structural” – violations that, as criminal law expert Rory Little has explained, “are so fundamental and difficult to quantify” that a defendant does not need to show that they changed the outcome of a trial. The justices explained that, in McCoy’s case, English’s insistence on conceding McCoy’s guilt even after McCoy had objected blocked McCoy’s “right to make the fundamental choices about his own defense.” Moreover, they added, “the effects of the admission would be immeasurable, because a jury would almost certainly be swayed by a lawyer’s concession of his client’s guilt.” Therefore, the majority concluded, McCoy is entitled to a new trial, without having to show that he was harmed by English’s strategy.

One of McCoy’s attorneys hailed today’s decision, declaring that, although “rare in the rest of the country, what happened to Mr. McCoy was a part of Louisiana’s broken criminal justice system that fails to respect individual human dignity. Mr. McCoy’s was one of ten death sentences imposed in Louisiana since 2000 that have been tainted with the same flaw.”

Cato’s Jay Schweikert, meanwhile, calls the decision a victory for Defendant autonomy:

The Supreme Court’s vindication of McCoy’s autonomy is all the more crucial because the jury trial itself—that cornerstone of American criminal justice—is fast vanishing to the point of practical extinction. Our Constitution and legal heritage are premised on citizen participation in the criminal justice system. But today, more than 95 percent of criminal convictions are obtained through plea bargains, in which prosecutors can bring insurmountable pressure against defendants. Even innocent defendants are often forced to plead guilty, simply because the threat of a much harsher sentence at trial is too great. And coercive plea bargaining is exacerbated by the practical inability of most appointed defense counsel to subject prosecutions to meaningful testing. Public defenders are saddled with impossible caseloads, with individual attorneys often required to manage hundreds of different felonies per year, and even more misdemeanors. The role of defense counsel, intended to serve as the defendant’s trial advocate before a jury, has largely been reduced to that of plea negotiator.

There’s no easy solution to the problem of coercive plea bargaining, but the least we can do is not discourage trials even more than we already have. Jury trials entail risk and uncertainty, but the defendant should know that he will have a zealous advocate, committed to defending his innocence and putting the state to its burden.

As I noted at the start, it seems to me that the answer to the underlying question that this case presents was self-evident from the start and I’m somewhat surprised that the case needed to be appealed this far to get to this result. The law has long been that, while attorneys have the authority to make some decisions on behalf of their clients when it comes to trial strategy, there are some decisions that can and should only be made by Defendants themselves. Among the areas where the attorney properly has autonomy are those that have to do with trial strategy such as what legal theories to pursue, what questions to ask a witness on direct or cross-examination, when to properly object to a line of questioning from opposing counsel, and, to some extent at least, whether to object to particular jurors during the process of jury selection. A defendant may object to decisions their client makes in these areas, but they don’t necessarily have the right to make the decision on how to proceed in this area. If they feel strongly enough about the matter, of course, they can seek to employ new a new attorney or petition the court to appoint a new attorney, although that will to some extent be within the discretion of the court in the case of court-appointed counsel.

When it comes to more fundamental matters, though, it is axiomatic that Defendants are the only ones who ought to have authority to make a decision. These areas include, but aren’t limited to, whether or not to seek a jury trial, whether or not the defendant should testify at trial, and, as we see in this case, whether or not to plead guilty or concede guilt during the course of the trial. An attorney can advise their client on these matters and, behind closed doors, make as vehement an argument as they wish to their client for why he or she should decide to take one course or another on any of them. In the end, though, the ultimate authority to make these decisions lies with the client and an attorney who disagrees must either carry out their representation as their client wishes or seek to be removed from the case as provided by the applicable rules of court.

What is impermissible is exactly what happened here, when the Defendant’s attorney explicitly went against his client’s instructions. In addition to being a violation of the defendant’s Sixth Amendment rights, it is an unethical act under Rule 1.2(a) of the American Bar Associations Model Rules Of Professional Conduct, which states that an attorney ”lawyer shall abide by a client’s decisions concerning the objectives of the representation.” In that regard, there are few things more fundamental to the objectives of the attorney’s representation of the client than the determination of whether or not to concede guilt. The strategy that McCoy’s attorney pursued is not an uncommon one in death penalty cases, and it may well have been the smarter strategy notwithstanding the fact that McCoy was ultimately sentenced to death anyway. That’s a matter of hindsight, though. At the time the trial was proceeding, only McCoy had the authority to make that decision, and his attorney clearly violated his rights in not proceeding as he wished.

Here’s the opinion:

McCoy v, Louisiana by Doug Mataconis on Scribd

Okay, I’m definitely not a lawyer – I don’t see how anyone could think otherwise. Given this doesn’t seem to be a political case, why did three of the conservative judges disagree?

The argument the dissent makes is that the Defendant’s attorney didn’t explicitly concede guilt, and argued throughout the trial phase of the case that the Defendant was not guilty. Therefore, he had not really substituted his judgment for that of the Defendant. While I see the point they are making there, I think that the mere fact of the attorney having admitted that there was a killing that his client was culpable for, while still arguing that he was not guilty under the law, was a bridge too far.

Is this one of those water is wet moments? You know, when science ends up confirming something we already know but hey, now it’s an official fact with data behind it?

English did not do as his client instructed. That is abundantly clear and arguing that he technically didn’t admit guilt misses the point that he admitted ANYTHING against the wishes of his client. I don’t care if he’s the guiltiest MOFO ever; if he says “I didn’t do it” and “I’m not copping to jack”, then you as his attorney dutifully comply. You don’t get to decide and if you can’t work like that, you hand it off to someone that can. Playing weasel words can backfire spectacularly, especially with a jury that’s not into subtle legal and ethical distinctions. “Yeah I killed them but it wasn’t really murder” isn’t going to fly well, as Mr. McCoy found out.