Tricks of the Polling Trade

Interesting:

Who you gonna call? Tricks of the polling trade (Seattle Times)

It’s hard work teasing the truth out of people to track trends and gauge attitudes in a nation of 200 million potential voters. Pollsters don’t always get it exactly right. But there are a few things they think they know for sure:

̢ۢ Based on history, only about 100 million of those potential voters will actually vote.

• You need only 1,000 likely voters for a reasonably accurate national poll. Double the sample size and you double the poll’s cost, but not its accuracy.

• It’s usually a woman who answers the phone. So to get enough men to balance a survey, interviewers must ask to speak to the oldest male in the household, or to the voting-age male who had the most recent birthday. And it’s best to interview only one person per household.

• Never, never attempt to poll on Mother’s Day.

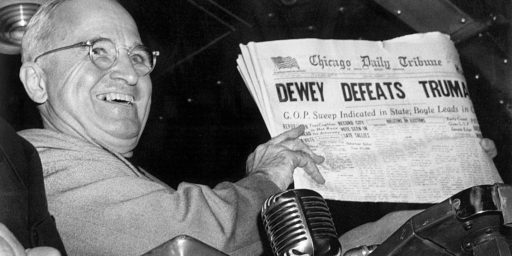

Call it science, craft or profession, modern public-opinion pollsters have been working to perfect what they do since 1936, when the Gallup organization predicted Democrat Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s second-term victory over Republican Alf Landon.

They’ve improved considerably since 1936.

Polls have a short shelf life. They are a snapshot at a moment in time, not necessarily a projection of the future. Events like conventions and debates can change opinions almost overnight. Indeed, 8 percent of American voters are likely to change their votes in the last month before an election, and 4 percent are likely to do so on Election Day, according to a study published in this month’s issue of Political Science and Politics, a journal of the American Political Science Association.

So as Election Day gets closer, pollsters supplement their technique. They survey 200 voters on each of three nights and aggregate the results. Each new day, an additional 200 are added and the least recent group is dropped. “This allows us to keep track of night-to-night changes as a back-and-forth really gets going,” said Democratic pollster Celinda Lake. “But there is a danger of overreacting to the shift that takes place on one single day, so these polls are often misinterpreted.”

Pollsters must hurry to complete each survey within a couple of days, said Andrew Kohut, director of the Pew Research Center for the People and the Press. “Certainly, when opinions are changing, if you take more than four or five days, you are likely to find yourself part of the next trend.” Although many people think polling is unreliable because different polls show wildly differing results, among the most respected national polls, results usually are tightly clustered. They may differ a bit, but not by much.

Polls taken months before an election are parlor games from the point of view of an average consumer. They’re the political equivalent of the pre-season college football forecasts: they give junkies something to pore over and dissect before the games start. They can provide meaningful information for candidates, though.

Experts may average the results of several polls to calculate how a race is going, sort of “a poll of polls, and that’s not bad. In fact the record over the years has been good,” said independent pollster John Zogby.

Like the RealClear Politics average, for example. It evens out the disparities among the polls, minimizing the effect of outliers.

Some pollsters distrust results they get on certain days. Polling the Monday before an election is useless, said Republican pollster Bill McInturff: “People clam up, they stop talking to pollsters. We’ve had very bizarre data on the Monday before election Tuesday. Undecided goes way up.” “We don’t poll on Friday nights,” said Democratic pollster Mark Penn. “Or on Halloween,” McInturff said. Wednesday, he added, is a bad night in certain Bible Belt areas where large numbers of voters go to church twice a week. Weekend nights — Friday and Saturday — are bad because younger and more affluent voters are less likely to be home, pollsters believe. Voters who do answer calls those nights add up to a “more downscale” group, McInturff said — more likely to be Democratic. That discovery is a legacy of the Reagan years. “Reagan’s support would dip in polling on Friday and Saturday nights,” McInturff said, “and then on Monday it would be right back where it was.” Lake avoids Fridays too, but for the opposite reason. “We never poll on Friday night because more Democrats are likely to be out,” she said. “Friday is bowling night and there are Friday night football games so you get fewer blue-collar people at home. “Same for Saturday,” she said. “Because younger suburban couples, two-earner families, are out doing stuff. Sunday night is a good time to get everybody, but we never call on Sunday morning because religious voters are likely to resent it. You don’t poll during the Super Bowl football game if you want men.” Mother’s Day is notoriously impossible for all pollsters. “That’s like death, the lines are all jammed, we just give up,” McInturff said.

So: no polling on Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Friday, or Saturday. According to my extensive research, that means polls should be conducted on Thursday and Sunday. Unless it’s Mother’s Day, of course.

I also wonder how the ubiquitous proliferation of cell phones has affected polling. I don’t have a home phone–just a cell phone. I know lots of other people in the same boat.

If I didn’t need land line for TiVo and DirecTV, I’d be in that boat, too.

Something curious happened during the last Canadian election. With the governing Liberals knee deep in the huge “sponsorship scandal”, polls showed the traditional support for the Libs in Ontario had softened and at one point the Conservatives were actually ahead.

Yet, when they actually voted, they returned mostly Liberals to parliament from Ontario – the suspected reason for the polling discrepency? It was thought that Liberal supporters were embarrassed to admit they were voting for the scandal ridden party.

But when they went to the polls, they voted for them in the privacy of anonymity.

I haven’t spent enough time in the US to know if the media pileon of Bush may be having a similar effect on some supporters – but I wonder….