Web Is Dead – Long Live the Internet?

Wired proclaims, "The Web Is Dead. Long Live the Internet." It's great linkbait but completely wrongheaded.

Wired editor-in-chief Chris Anderson and Michael Wolff proclaim, “The Web Is Dead. Long Live the Internet.”

This is not a trivial distinction. Over the past few years, one of the most important shifts in the digital world has been the move from the wide-open Web to semiclosed platforms that use the Internet for transport but not the browser for display. It’s driven primarily by the rise of the iPhone model of mobile computing, and it’s a world Google can’t crawl, one where HTML doesn’t rule. And it’s the world that consumers are increasingly choosing, not because they’re rejecting the idea of the Web but because these dedicated platforms often just work better or fit better into their lives (the screen comes to them, they don’t have to go to the screen). The fact that it’s easier for companies to make money on these platforms only cements the trend. Producers and consumers agree: The Web is not the culmination of the digital revolution.

[…]

The Web is, after all, just one of many applications that exist on the Internet, which uses the IP and TCP protocols to move packets around. This architecture — not the specific applications built on top of it — is the revolution. Today the content you see in your browser — largely HTML data delivered via the http protocol on port 80 — accounts for less than a quarter of the traffic on the Internet … and it’s shrinking. The applications that account for more of the Internet’s traffic include peer-to-peer file transfers, email, company VPNs, the machine-to-machine communications of APIs, Skype calls, World of Warcraftand other online games, Xbox Live, iTunes, voice-over-IP phones, iChat, and Netflix movie streaming. Many of the newer Net applications are closed, often proprietary, networks.

And the shift is only accelerating. Within five years, Morgan Stanley projects, the number of users accessing the Net from mobile devices will surpass the number who access it from PCs. Because the screens are smaller, such mobile traffic tends to be driven by specialty software, mostly apps, designed for a single purpose. For the sake of the optimized experience on mobile devices, users forgo the general-purpose browser. They use the Net, but not the Web. Fast beats flexible.

[…]

Monopolies are actually even more likely in highly networked markets like the online world. The dark side of network effects is that rich nodes get richer. Metcalfe’s law, which states that the value of a network increases in proportion to the square of connections, creates winner-take-all markets, where the gap between the number one and number two players is typically large and growing.

[…]

On the underlying Internet itself, Good Enough has won. We stare at the spinning buffering disks on our YouTube videos rather than accept the Faustian bargain of some Comcast/Google QoS bandwidth deal that we would invariably end up paying more for. Aside from some corporate networks, dumb pipes are what the world wants from telcos. The innovation advantages of an open marketplace outweigh the limited performance advantages of a closed system.

But the Web is a different matter. The marketplace has spoken: When it comes to the applications that run on top of the Net, people are starting to choose quality of service. We want TweetDeck to organize our Twitter feeds because it’s more convenient than the Twitter Web page. The Google Maps mobile app on our phone works better in the car than the Google Maps Web site on our laptop. And we’d rather lean back to read books with our Kindle or iPad app than lean forward to peer at our desktop browser.

While these trends are obviously happening, I’m dubious that they’ll revolutionary rather than evolutionary.

After all, it’s not like the Internet of 2005 was the Internet of 1995. During that time, we went from most people (or, at least, most Haves in Western countries) not being online to them being online. From the Internet being accessed through the likes of CompuServe and AOL to local ISPs. From 2400 baud dialup to blazing fast broadband considered a birthright. And the nature of the content available on one’s browser changed even faster than did the browsers themselves.

So, now the Internet is available to an increasing number of us on our smart phones. But saying that this makes it no longer “the Web” is like saying that the iPhone is no longer a phone because it’s portable and does things other than carry voice conversations.

GigaOm‘s Matthew Ingram (“The Web Isn’t Dead; It’s Just Continuing to Evolve“) agrees.

Om’s favorite comparison is to the real world of home appliances: we don’t just have a single all-purpose appliance — instead, we have toasters and coffee-makers and can-openers and other devices that perform specific tasks. So, too, we now have applications for maps, applications for photos, applications for reading books, and apps for video and location-based “check ins” and dozens of other things. That doesn’t mean the web is dead; it means that the web, and the way we use it, is evolving. Instead of wandering around on the web looking for interesting websites by using services such as Yahoo or AOL, we’re using task-specific devices in a sense.

Anderson is right in a technical sense when he says that the web is “just one of many applications that exist on the Internet, which uses the IP and TCP protocols to move packets around.” But he also gets it wrong when he conflates the demise of the web browser with the demise of the web itself. Plenty of applications are using web technologies such as HTTP and REST, just as web browsers do. In a sense, they’re like mini-browsers for discrete applications, and although it’s almost a footnote in the Wired piece, HTML5 has the potential to allow developers to create (as some already have) websites that look and feel and function exactly like apps do.

Valleywag‘s Ryan Tate snarks, “Wired Says ‘The Web is Dead’ — On Its Increasingly Profitable Website.”

- Irony 1: Wired released its cover story package first to the Web, on Wired.com. You won’t find it in Wired‘s iPad edition, and it’s not out in print yet. The death of the web might be the “inevitable course of capitalism,” but it apparently pays better to deliver that news via a dying medium.

- Irony 2: Revenue is up at Wired‘s profitable website this year, despite a fairly severe reduction in staff last year. Yet Anderson, who has no control over Wired.com, writes that most Web publishers haven’t been able to “reverse the hollowing-out trend of analog dollars turning into digital pennies… and by the looks of it there’s no light at the end of that tunnel .” That tunnel being the one Wired, itself, is not in, apparently.

- Irony 3: At the same time, circulation — and thus revenue, almost surely — are down for Wired‘s iPad edition, which was approaching (and possibly even surpassing) 100,000 copies for the debut issue but has since fallen off — to less than a fourth of what it was, one source claims. However large or small the decline, it could certainly be corrected; dropping off from a big bang launch is common enough in print and online media alike.

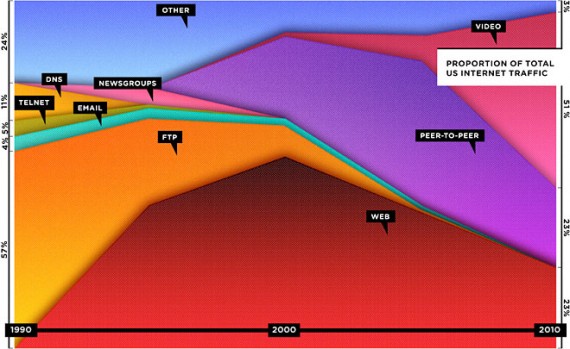

Finally, boing boing‘s Rob Beschizza points out (“Is the web really dead?“) comments, as have others, on the chart which tops the Wired feature:

Without commenting on the article’s argument, I nonetheless found this graph immediately suspect, because it doesn’t account for the increase in internet traffic over the same period. The use of proportion of the total as the vertical axis instead of the actual total is a interesting editorial choice.

[…]

In fact, between 1995 and 2006, the total amount of web traffic went from about 10 terabytes a month to 1,000,000 terabytes (or 1 exabyte). According to Cisco, the same source Wired used for its projections, total internet traffic rose then from about 1 exabyte to 7 exabytes between 2005 and 2010.

[…]

It’s also worth adding that bandwidth, though an interesting measure of the internet’s growth, isn’t so good for measuring consumption. It doesn’t map to time spent, work done, money invested, wealth yielded… Does 50MB of YouTube kitteh represent more meaningful growth than a 5MB Wired feature? And, as others point out in the comments, many of the new trends are still reliant on the web to work, especially social networking.

He presents alternate charts depicting that reality; I encourage you to click through for yourself.

TechCrunch‘s Erick Schonfeld (“Wired Declares The Web Is Dead—Don’t Pull Out The Coffin Just Yet“) thinks the lumping in of Web-viewed YouTube videos into “videos” as something mutually exclusive from Web is misleading. I agree.

Paul Graham just posted an essay on Addictiveness.

What we’re seeing is people moving to the cigarettes of the internet, i.e, more efficient delivery systems of the “connected” high. All the changes listed by Wired are just more focus, concentrated, segmented forms of the addictive substance. Mobile devices just let you take a concentrated dose along where ever you go so naturally people will sip from it more than down at the local browser. Straight up with no tiny little umbrellas.

I particularly liked this characterization of the iPad in the footnotes:

” In other words, it’s a hip flask. (This is true of the iPhone too, of course, but this advantage isn’t as obvious because it reads as a phone, and everyone’s used to those.)”

Then the IPhone would be a nip, right?

I assume that they measured “traffic” in bytes, and not low-level requests. That makes a very skewed representation. Consider this page. We are all here for the text, and most low-level requests are for text, but the bulk of the bytes we exchange are for the images.

Therefore we are here for the images? I think not.

A proper study of usage would have to factor traffic into eyeball time, to see how much is reading, how much is watching, and how much is listening.