When Work Interferes With Work

The push to return to the office comes with domestic consequences.

In “THE OTHER WORK REMOTE WORKERS GET DONE,” The Atlantic‘s Stephanie H. Murray argues, “Telecommuting allows caregivers to manage a workload that is, if anything, way too big.”

Predicting the future of remote work is hard. On one hand, many American workers really like it and want to be working remotely even more than they are now (though, of course, many workers have never had the option to work from home). And while the amount of work in the U.S. being done remotely is down from its pandemic high, it’s been holding steady near 28 percent for about a year now. In a tight labor market, many employers opted to embrace at least some remote work to help with recruitment and retention.

On the other hand, many employers are getting more vocal about their desire to have employees in the office more often.

[…]

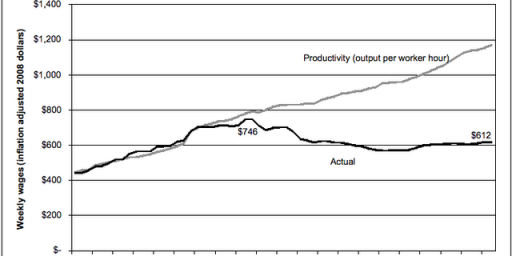

The shift seems to reflect a concern long voiced by executives and managers and backed up by some recent research: that remote work is hampering productivity. One study found that data-entry workers who worked remotely in India were 18 percent less productive than their in-office counterparts. Another working paper published in July found that fully remote workers were about 10 percent less productive than their in-person counterparts (though hybrid work seemed to have no significant effect on productivity).

So, employers want their employees to come to work and be productive. Which isn’t surprising!

The appeal of remote work is all too often glossed over as a matter of “quality of life” or “work-life balance.” Those are, of course, important. But that framing also ignores the uncompensated caregiving that Vigil and millions of others provide for America’s young, sick, elderly, and disabled. Their efforts are not just a quality-of-life issue; they’re an enormously important and overlooked part of our economy. For a lot of caregivers, telecommuting allows them to manage a workload that is, if anything, way too big. Remote work, then, isn’t just a question of work-life balance; it’s a question of work-work balance. The traditional conception of “productivity” doesn’t account for this.

Well . . . no. Why would it?

To be sure, there’s a lot of work that takes place inside the home. My wife and I do a lot of it even after outsourcing some of it (weekly housecleaning and fortnightly lawn service). We’ve benefitted tremendously from my wife, and to a much lesser extent me, having the ability to telecommute and manage, for example, school dropoff and pickup. But, of course, that doesn’t accrue to the balance sheet of employers, who are, after all, paying for people’s time during working hours.

For years, feminist economists have complained that the primary methods by which we measure the size and health of the economy leave a whole lot out. GDP, for example, primarily measures goods and services bought and sold in the market economy, excluding those produced by households. Our entire economy hinges on human labor, but the unpaid work that goes into raising a productive laborer is absent from economic indicators. When someone like Vigil leaves their job to care for a family member full-time, they are considered economically inactive. Apart from the money parents and taxpayers spend on children’s care and education, human capital “just sort of pops up” in the national accounts as a fully grown, hard-working citizen, Julie P. Smith, an honorary associate professor at the Australian National University who has written extensively on this topic, told me.

All of this makes for a distorted picture of the economy. Because household production counts for nothing in national accounts, the bump in GDP that results when production shifts into the formal market, such as when a stay-at-home mother enrolls her child in day care and starts a full-time job, is exaggerated. We witnessed the reverse of this during the pandemic—one recent report found that when you account for unpaid household production, the drop in economic activity that occurred during the pandemic was much less severe. This makes sense; a lot of the work previously done by paid laborers didn’t go away—it just shifted into the home. “Instead of going out to a restaurant and eating a meal … a family cooked their own meal in their home. And when they cook their own meal in their home, all of a sudden, they disappear from economic indicators, even though somebody still had to put in the work to, you know, cut the vegetables and cook the meat or fish or whatever it is,” Misty Heggeness, a professor at the University of Kansas who is working on a dashboard aimed at quantifying the care economy, told me. That makes a difference to the restaurant business but not as much to the nation’s productivity as a whole.

These are not novel ideas. Feminists have been talking about the value of unpaid housework for as long as I can remember—going back at least half a century now. And, at some level, the argument has merit: my house is clean and my belly is full regardless of whether I perform the labor myself (as I usually do) or I outsource them to a cleaning service or restaurant (as I occasionally do).

But the reason this obvious fact still hasn’t been accounted for in economic statistics is that this isn’t what the economic statistics are trying to measure.

If I let my housecleaner and lawn service go and perform the labor myself, my house will be roughly as clean and my lawn roughly as kempt. But the people who used to perform those services will now have less money to feed their families and pay their bills. That’s a negative impact on the thing we think of as “the economy.”

Heggeness thinks the lack of comprehensive data on this sort of work is part of why experts took so long to wrap their head around the so-called she-cession. Many assumed that the increased child care brought on by school closures would disproportionately oust mothers from the labor market. It wasn’t until pretty late in the game that it became clear that risk had been overstated. “We’re not good at telling the comprehensive story of the economy, because we completely ignore all the economic activity that is done within homes,” Heggeness said.

Because unpaid activity is, by fucking definition, not economic activity. This is also true outside the home. People who volunteer to be youth softball coaches or to feed people in soup kitchens aren’t measured in the GDP, either. This here blog post is not economic activity. If The Atlantic were to pay me $500 to write a thousand words of nonsense, it would be economic activity.

How we measure—or mismeasure—the economy inevitably influences policy making. “What we measure reflects what we value, and shapes what we do,” Smith and her co-author, Nancy Folbre, wrote in a 2020 paper on the subject. The omission of so much domestic work from economic indicators makes policies that support caregiving look like bad investments. Both breastmilk and formula are suitable sources of nutrition for newborns—but only the latter has any economic value as far as GDP is concerned.

Unless it’s being sold, that’s true. So, for example, if I pay a dollar for a beer, that’s economic value. When I piss the beer out, it’s not. Yet both are liquids! How does that make sense?

If an expansion of paid parental leave allowed more new mothers to breastfeed their kids more and rely on formula less, the economy would “suffer” as a result.

Correct. Because, again, if formula factories shut down—or are less profitable and have to lay off workers—people have less money to buy things. In the economy.

A similar tipping of the scales seems to be playing out in the debate about remote work: The work that the practice is allegedly hampering is overshadowing the work that it enables.

So, there’s no “allegedly” to it. The evidence is pretty clear that most workers do less of the work that they’re being paid to do remotely than they do in the office. And that’s the only work that the employer is interested in measuring.

Speaking for myself, I’m differently productive at home and at the office. I’m more able to do parts of my job as department head at the office. It’s much easier to observe my colleagues’ teaching there than it is remotely. While I could certainly do meetings and other collaborative work via Zoom or Teams, it’s generally more productive to do it in person. On the other hand, I’m much more able to do work that requires intense concentration at the house. Not only are their fewer interruptions but I save 90-plus minutes of commuting time. And, as a bonus, I can do things like laundry and load/unloading the dishwasher at times when I need a mental break.

Indeed:

The most obvious benefit of remote work is that it saves people time commuting. Many American workers sink that extra time into their job—others, and particularly those with kids under 14, devote some of it to caregiving. For Sarah White, who works full-time for a pharmaceutical company, the absence of a commute makes managing her son’s complex medical needs far easier. If she worked in the office, each medical appointment would require multiple trips between home, school, the office, and the doctor. But because her son’s school is three blocks from her home, midday appointments are pretty simple. “I can pop in my car, take him to his appointment, pop him right back to school,” White told me. And she uses slack time throughout her day in a productive manner. “I can throw in laundry and just keep it going … because it’s right next to my office,” she said.

Employers may not like to hear that employees are doing chores on the job, but working in an office doesn’t eliminate downtime—it just restricts how you can use it. Without the option of loading the dishwasher in between meetings, you might chat with a co-worker or check social media. Research backs this up: A survey of workers from June found that those working from home were more likely than their office counterparts to run a personal errand, care for a child, or do chores during the workday—but slightly less likely to play a phone or computer game or read for leisure.

Again, I think it really depends on the nature of one’s job. The more labor-intensive it is, the more likely the workplace is productive. The more thinking-intensive, the more likely remote is more productive.

A subtler point is that when it comes to caregiving, just being nearby is valuable, not because someone needs you at every second but because at any second they might. This is an aspect of caregiving that is all too easy to overlook until something goes wrong. Vigil’s area has seen a string of big storms lately, and she happened to be in the office during a downpour that caused a tree limb to fall in her yard. At home alone, her son panicked. Working from home enables her to ensure that he’s okay—both emotionally and physically—during those sorts of unpredictable events.

If you account for all of the caring that remote work has made possible, it amounts to an increase in productivity with positive implications for the economy. Compelling evidence suggests that remote work is allowing caregivers to remain employed; it may be why labor-force participation for women with kids under 5 has leapfrogged its pre-pandemic rate. It may also allow workers to do more caregiving. Lynn Abaté-Johnson, who wrote a book about the six years she spent caring for her mother who had cancer, told me she could not have taken on such a large role in her mother’s care if she hadn’t been able to work remotely.

So, again, this is quite valuable. That it doesn’t impact “the economy” doesn’t mean it doesn’t have worth. But, surely, accounting for these things isn’t something that businesses should be responsible for financing.

And, as the pandemic made so starkly clear, there’s a huge privilege gap at work. While there would be some shifts in productivity, I could do my job remotely indefinitely. That’s just not true for entire sectors of the workforce. Everything from stocking shelves to pouring concrete to meatpacking to movie making to open heart surgery requires people to be physically present at the workplace.

If concerns about our aging population and declining fertility rate are to be believed, then remote work is exactly the kind of thing the United States ought to be embracing. Studies show the flexibility of remote work may be allowing people to have more kids. And even if telework alone can’t raise the fertility rate, it would at least allow more workers to help care for the elderly. Of course, a rethinking of productivity to include care shouldn’t end with embracing remote work. Many other policies, such as paid family and medical leave, paid sick leave, child allowances or cash support for other unpaid caregivers, and predictable and flexible scheduling practices, could ensure that Americans—especially those who can’t work from home—can care for the people in their lives. Even if that means Americans give a little less of their energy to their employers, the greater investment in the people who make up the nation’s economy is worth it.

So . . . sure. Children, the elderly, the disabled, and others need care and there are societal questions about who should provide and pay for that care. But these are mostly public policy decisions, not questions about employee-employer relations. More flexible working conditions may be part of the solution but, again, that’s not really possible for a whole lot of jobs.

This is reflective of a very American way of thinking about our lives and our work – everything is a purely transactional relationship and the only stakeholders a company really needs to be concerned with are the stockholders.

This is a change from past generations – and other countries – where companies considered many stakeholders – the community, employees, suppliers, stockholders, customers, the country, etc.

The transactional nature of employment – and everything else corporate America does – exacerbates the family problems described in James’ piece here, but it also contributes to pollution, homelessness, and our terrible healthcare system.

Live by the sword, die by the sword.

@Tony W:

At the end of the day, employers pay employees for their work. It’s inherently transactional. Good bosses/companies will allow employees flexibility to take care of personal/household/family businesses during work hours but, even that, really depends on the nature of the relationship because it’ll make employees happier, more productive, and more likely to stick around. It’s much easier to do that for managers and knowledge workers than it is for lower-level workers in the service economy.

@James Joyner:

This has only been the case since the early 80s (there’s a specific SCOTUS case that established corporations being about profits above all else, but i forget the name.)

For most of the country’s history, corporations existed primarily to serve some community purpose and any profit was only to attract necessary capital, not the primary goal.

Anecdotally, as someone in direct patient care (occupational therapy), the number of people therapy sees has increased since WFH has expanded. The flexibility provided for scheduling appointments has led to an upward tick in billable hours for our profession. Does this point factor in to any sort of economic mathematics?

Yes, kinda. But also the evidence is a bit more complex.

For example, the conclusions of the now oft-cited National Bureau of Economic Research working paper that found “data-entry workers who worked remotely in India were 18 percent less productive than their in-office counterparts” also found thus:

– those with a preference for remote work were 12% faster and more accurate at baseline

– 2/3 of the difference in productivity between those randomly assigned to either remote or in-office work was due to first day discrepancies, with the other 1/3 due to faster learning by in-office workers in subsequent weeks

– remote productivity drop-off was highest for poorer households and workers with more in-home responsibilities, like childcare

All this suggests a more thoughtful and nuanced WFH policy than ‘My Indian data workers must work in office because productivity.’

For example, ‘New hires must work in-office for the first twelve weeks before switching to remote work. Those whose speed and accuracy decline may be required to return to office. Employees with family care responsibilities are encouraged to work with their managers to find acceptable hybrid work schedules.’

Or some such.

@James Joyner: It doesn’t have to be purely transactional.

Employees could be seen as partners with the owners and could share in the rewards more fully. We could reject raw capitalism in which only the rewards are privatized. We could give strong protections to workers – including universal health care – and reduce corporate power over our lives.

But we won’t.

Regulatory capture has expanded beyond niche industries to the economy as a whole.

I know I sound like a socialist, but without proper regulations, you get what we have here today – billionaires mopping up every last dime they can squeeze out of the other classes.

We are already on the brink of (cold) class-warfare. One of Reddit’s most popular subs is /r/antiwork.

If we don’t start regulating corporations more effectively to reduce their power, and change the tax scheme to force the ultra-wealthy to pay according to the benefits they accrue from the larger society, I am worried there will be a hotter conflict.

@Bnut: Money moving from one industry (say downtown restaurants and bars) to another (therapists) generates pushback from the losing industry, but the winning industry is, understandably, silent about it.

My guess is that we’re not accounting for these changes.

It is saddening to see these who long to return to the manor, estate, or ship. The lord or captain responsible for all aspects of the villein’s/crewmembers life. Only now to serve the corporation rather than the noble family. The life of the servant didn’t fade for long before the longing returned.

See the Admiralty laws covering crew signing on for a voyage. The Maintenance and Cure due if injured on the voyage. The crewmember unable to leave the ship until it returns to the port of departure (without permission of the master). But also the master not allowed to leave a crewmember in foreign port (consulate aids their repatriation and charges the ship the costs). Oh, things are easier, simpler, cheaper now if these are broken, but the laws and customs remain.

Even in the old cowboy movies, these customs lingered in the background. The wrangler signed on for a round up or drive, and was required to remain, doing as he was told, provided food, and if necessary medical care by the rancher.

All good you say, and the bad powers granted the master have been trimmed down, but will they remain if the demands rise again?

@Stormy Dragon:

I’m not sure where this comes from. While incorporation can be used in the way you have described, by far the most common form of corporation is the purely commercial and that’s been true since at least the Dutch and British East India Companies were formed half a millennium ago.

@Tony W:

It happens. In fact, a beloved coffee shop closed down recently in Baltimore and is reopening as employee owned. But, well, we’ll see how that goes. I suspect that in most cases the employees would not be willing to accept the risks. I’m thinking of one company I know whose profits will be down more than 50% this year and last year was mediocre, meaning the owners could have made more money even last year with the same capital by simply putting it into fairly safe investments. This year is grim. How many of the employees would be willing to reduce their salary in the down years as well as accept bonuses in the good ones? This particular company does offer yearly bonuses that are theoretically tied to company performance but for at least the past 25 years they have always paid in full regardless of how the company performed. Needless to say, it is a privately held company.

I agree that companies should treat their workers fairly and with empathy. But if a company doesn’t make their numbers it goes under and gets sold for scrap, and then no one has a job. It’s hard to keep a business going. It doesn’t just happen.

Speaking as an employer it is clearly transactional. The employees work and they get paid. That said, as an employer you can choose to treat people well and provide them benefits that go beyond the transactional nature. Work at home is possible for the small number fo people who can do it. We have very flexible hours and we use a combination of computer scheduling and a fair bit of manpower to make it work for people. I and my other senior staff make it a point to get to know our people so if we know someone is having trouble we can offer help, giving them a higher schedule or sending them early if we can. We provide some free training and make sure we have social get togethers so everyone can meet and talk outside of work.

What I think I see is that most people appreciate this effort. We actually are paid a bit less than our major competitor where they have historically treated their staff poorly. We have hired over a dozen of their staff while none of ours has ever left to go work for them, even with the higher pay. That said I still think there are at least a good 5%-10% of people who are close to pure mercenaries. The pay is all that matters. They stay for family or convenience reasons but complain.

Steve

Directly related to the topic of managing work-work balance (unpaid caregiving and full time work), but tangentially related to the topic of “the economy,” not enough people know that FMLA protections apply to caregiving and not just the individual’s health needs, apply to the usage of both paid and unpaid leave (the legal protections don’t just kick in once you’ve burned through your paid leave) *AND* that FMLA protections can be used to apply to intermittent leave if the circumstances allow for it.

I’ve been using intermittent FMLA for a while now to help make caring for my mom alone more manageable. For folks unfamiliar, FMLA allows for up to 12 weeks of protected leave in a calendar year (you use all paid leave first, then go into unpaid). Most people take it in chunks to leave work temporarily (while they recover from surgery, for example). But intermittent FMLA allows you to take leave on an as needed basis. I use it to cover the times I need to help out my mom or manage things at the house during the work week. Over the course of the academic year, it’s probably averaged out to about 4 – 6 hours per week.

I’m fortunate that I’ve got enough sick time banked that I haven’t needed to worry about dipping into unpaid leave and likely won’t for a couple of years. And, frankly, I still do the same amount of work even if I am using FMLA leave in a given week – I’m just shifting it to untracked WFH hours in the evenings.

@Bnut:

I really thought you were going to make the point that a lot of people have crappy home office setups, and that we were seeing the results of these ergonomic failures in their bodies.

I guess I’ve just been lucky in that all of my jobs have been flexible enough that I can just schedule medical appointments for whenever. Or I’m oblivious enough to not notice how upset this made everyone.

@Stormy Dragon: Left fantasy and ledty version of past idealusation is poor actual economic history, as a cursory review of the historical record of the US “Gilded Age” or broader 19th century history of enterprises and economics, which if one bothers to rub some critical neurons together one would understand Marxism papnd communitarian, socialist, and communities reaction would hardly emerge…

Regardless, one is vanishingly unlikely to come up with coherent economic policy if one mistakes as implicit in comments broadly the visible publuc exchange listed companies as all enterprises. Roughly estimated fir USA, exchange listed (aka “publicly listed”) are about 50 percent of employment ex self employment.

The rest is quite a different mix, non-listed family companies, partnerships etc for the pretences and policies of listed companies as to duty is quite non-lieu.

If half of your employment is in quite the different legal and financial, basing general policy on that visible part of an iceberg rather will lead to inapt reaction and conclusions.

@steve:

I’ve been to my fill of company sponsored fun.

Part of the joy of working from home is not having to interact with your coworkers. My last job had a bitter and angry Trumper and an insane lefty guy who was stalking him (like, literally stalking outside of work, to see whether he was eating indoors during the lockdown, following him to parks to hide behind bushes photographing him fighting some other dude*, etc…) and they would regularly get into petulant arguments in meetings.

And I could turn them off.**

Now, this was an extreme example, and one or both of them should have been fired (insane stalker guy, definitely… angry Trumper… let’s see how he is without the insane stalker guy***), but there’s always something.

Work really is like a family. You don’t choose your family members, some of them are assholes, there’s constant resentment, and you’re supposed to act nice around them.

——

*: some people had the wrong takeaway from watching Fight Club.

**: “oh, look, I’m having networking issues” I would announce, before shutting off my wifi and vanishing, silencing my phone and just going for a lovely walk.

***: after the insane stalker guy left to go to another company, the angry Trumper really blossomed into an Angrier Trumpier angry Trumper. I’m not saying the lunatic stalker was right, just that it was really convenient the two most toxic people paired off against each other.

@Lounsbury: Churning maelstrom of obligations fiduciary and non-fiduciary viz. the incorporation thereof was upended from lefty ideations circa the pre-post-bellum era wherein the war between states necessitated increased capacity of an industrial nature. In furtherance, Intello Bobos might reflect upon the epistlutory ejaculations of Lincoln viz. the subject at hand.

Dominance of bespoke production during the previous era obligated novel structures to affect efforts greater than even the greatest man (Paul Bunion, with the cattle both azure and clinically depressed) as Adam Smith himself envisioned, but a rapid industrial policy repositioned the fulcrum between goods public and private, albeit with an increasingly confiscatory tax scheme that has been observed in the breach. Reconstruction in the North was more successful than the South.

Conclusions that said fulcrum is fixed in space are premature prattle of the landed gentry who are unaware of how aesthetically pleasing their visage would look upon a pike, halberd or other polearm.

@steve: Indeed it is of course transactional, and one shouldn’t engage in fantasy otherwise. Certainly I think – as an employer myself in an HR centric sector (investment) that investing in said employees is most sensible, but certainly can see in some sectors not so.

@MarkedMan:in respect to the coffee shop, in fact taking equity risk in small businesses (if we say simplistically under perhaps 100 employees, regardless of turnover) is statistically extremely high risk regardless of what country one looks at – and so more employee exposure to business risk really is not the great social advance some naive romantic views would have.

USA ERISA rules which I have had to familiarise myself with for USA employees are rather restrictive on employee ownership as form of remuneration and while for my own case I find it obnoxious, taking a step back it is quite sensible – equity ownership is also a lock-in for non-publicly traded companies and thus quite risky so really should have careful public policy…. and not naive romanticism.

In respect to the return to work at office, as an employer I am going in that direction as since end of pandemic emergency (as in lock-downs and travel restrictions) the comparative decline in team cohesion, the rise of non-availability to team members, and the real decay in transfer of skills to younger staff – and zero intern retention is just flagrant. During pandemic with lockdowns and restrictions this worked rather better.

It’s completely unworkable at scale, but I do wish US businesses would take a more compassionate, whole-life approach to the way they view their employees. Some employees have demands on their time and will be productive if provided the flexibility they need to make home + work, well, work.

The “nOboDY wAnTs tO woRK aNymOrE” that employers have been screeching about for a while now is likely being driven by exactly this tension. If an employee worked from home during the pandemic and has child/elder care demands–or any other mix of life issues–and they are told that’s no longer an option, it’s not easy to revert back to prior (if they even can–a lot of businesses they might have relied upon to make it work have closed or moved, etc.).

Employers have a choice, it seems: figure it out, or expect to lose a chunk of your workers. Some of the ones you lose will be high performers. Is it worth it?

@Lounsbury: How do you not realize that your content free insult screeds just label you as an irredeemable asshole? Your word spew is barely decipherable and definitely not worth the effort.

@Gustopher: Don’t ever stop doing this please lol

Also where’s the obligatory a noun, a verb, and “lefty fantasy?”

@Gustopher: You have a real feel for this type of commentary. Good work! 😀 😛

@Gustopher:

😀 😀 😀 😀

@Gustopher: My wife is WFH and does half her shit in bed. It drives me up the wall.

Not if you spent the money you saved on some other goods or services, which you probably would.

I understand and agree with the argument that when economists measure GDP, or its growth, or many other “economic indicators”, it necessarily means using money as the measuring tool. But such a technical argument avoids the larger questions of what exactly is being measured, and why, and what conclusions should be drawn from it.

For example, if everyone were suddenly to begin recycling their compostable waste, and growing as much of their own food as possible, the agricultural industry would take a big economic hit which would be reflected in GDP. In conventional policy-making terms, that would be regarded as an undesirable development. But nobody would be any less well fed, many would be healthier, and the environment would benefit both directly and indirectly. That’s the kind of point many critics make of using effects on “the economy” as the benchmark against which policy proposals should be evaluated.

@Lounsbury:

Apparently even Lounsbury merely phones it in when working from home…

Gustopher- Ours are all voluntary. Completely understand that some people dont want to see work people when not at work. What’s encouraging is that almost all of our people hang out with each other anyway. Some people who drive about 2 hours to work with us dont but no one care that they dont come to events.

Steve

@James Joyner: Of course a lot of the measurement problems could be solved simply by making commuting times mandatory work hours. A lot of the “problem” in measurements derives from the fact that employers are able to outsource part of the employment transaction costs.

Forcing employees to return to the office is a *massive* hit to employees.

People are aware of that.