Why Debating Districts Misses The Larger Point

There are plenty of other factors that help our two major parties retain power.

Undoubtedly one of the major themes of the upcoming book A Different Democracy, coauthored by our Outside the Beltway colleague Steven L. Taylor, is that many of the structural features of our system of government in the United States are the result of conscious choice rather than inevitability. As I regularly explain to the students who take my American government courses, we usually take for granted features of our political system and even assume they are either the one true way of doing things or the only way to do things, despite the fact we could choose very different approaches yet still accomplish our goal of having a representative national government.

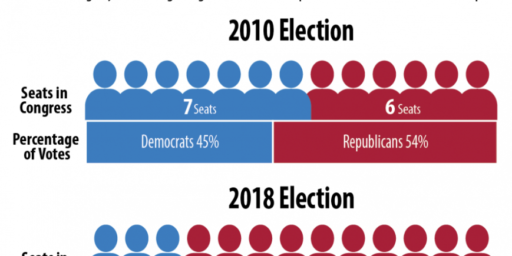

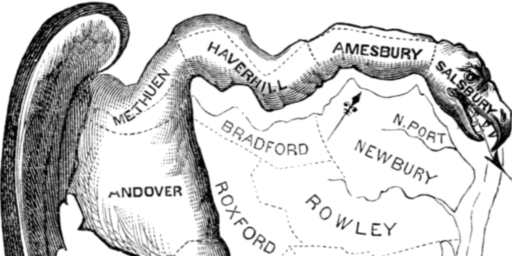

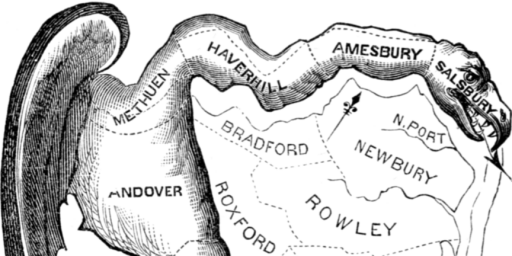

A case in point is the oft-discussed issue of congressional district boundaries in the United States (and, to a lesser extent, the district boundaries in state and local representative bodies as well). As political scientists, we regularly see new proposals to somehow generate “ideal” districts that will somehow purge our system of the perceived evils of partisan or ethnic gerrymandering; recently, Vox.com discussed one of these approaches, advanced by an engineer and a mathematician (somewhat tellingly, these proposals rarely come from social scientists) which would replace the often-squiggly lines between districts with a bunch of polygons, presumably taking the politics out of redistricting much as one might like to take the pee out of a public swimming pool.

Political scientist John Sides pointed out at the time that there are plenty of good reasons why we might want our congressional districts to look, well, weird, rather than being the result of mathematical formulae:

[P]retty little districts could actually be pretty terrible. That is, they could be terrible at doing what districts are supposed to do: engender good representation.

What’s good representation? Here are some answers that people regularly defend:

- Good representation happens when representatives are beholden to specific geographical communities, who are believed to have common interests. This is a reason to draw districts that correspond to existing cities, towns, and the like.

- Good representation happens when the largest possible majority of people get to elect the representative of their choice. This is a reason to draw lopsided districts with large partisan majorities.

- Good representation happens when groups who have been historically excluded from the electoral process — like racial and ethnic minorities — get to elect the representative of their choices. This is a reason to draw majority-minority districts (like the snakey NC-12, the subject of Shaw v. Reno and subsequent Court cases).

- Good representation happens when a district is politically competitive, which means representatives work harder to represent “the people” because there is always a good chance they could be thrown out of office. This is a reason to draw districts with a partisan balance close to 50-50.

This is an area of politics where the United States is something of an outlier; in most other countries with district-based representation (in whole or in part), districts are at least nominally created in a non-partisan process with somewhat more emphasis on maintaining communities intact and less emphasis on having equally-populated districts (the latter a result of the Supreme Court’s ruling in a 1964 case known as Wesberry v. Sanders). However, even in those countries the process is fraught with politics; the most recent redistricting review in England notably collapsed after the current Coalition government disagreed over the revised boundaries as part of a broader spat over electoral reform. Closer to home, the recently-established independent redistricting commission in California has faced criticism regarding exactly how independent its decisions were of the state’s Democratic Party majority in the 2010 redistricting cycle; around the same time, Arizona Republicans attacked their state’s independent commission as well.

If we can’t get the politics out of redistricting, what can we do? Many of the objectives Sides suggests (the representation of minorities, the representation of geographic interests, and more competitive elections overall) can be accomplished by using at-large representation or multiple-member districts as part of a broader scheme of proportional representation. Although at the extremes proportional representation can lead to a proliferation of minor parties, as has been the case in the Netherlands and Israel, assuming we were to retain the constitutional requirement that districts be wholly within a state, the effective electoral threshold (essentially, the share of the vote a party would need to get at least one representative) in all but the four most populous states (California, Florida, New York, and Texas) would be over 5%, which is actually quite high by world standards.

Even a system with a mixture of district-based seats and a compensatory proportional tier (like the system used in Germany and Mexico, as well as in Scotland and Wales for their devolved lawmaking bodies, which are generally referred to in the political science literature as a “mixed-member proportional” system) would minimize the rewards to partisan gerrymandering, as virtually any partisan gains in the district seats from gerrymandering would be lost at the proportional level.

Of course, the one potential disadvantage—at least from the vantage points of the two major parties—of a move away from single-member districts with winner-takes-all elections would be some degree of erosion of the Republicans’ and Democrats’ duopoly in American politics; however, there are also plenty of other factors that help our two major parties retain power, and eliminating one of them would not necessarily displace the two dominant parties from their overwhelming supremacy within our system.

That First District of Colorado pictured above is exactly why you can’t use pure statistics to generate reasonable districts. The map makes perfect sense once you know where Denver International Airport is.

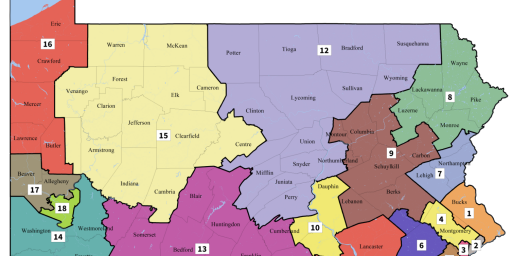

Also your PA-12 looks wrong. Are these maps old?

@Pinky: I believe these maps are from the 2002-10 redistricting cycle; I just grabbed some clipart we had already for gerrymandering.

@Chris Lawrence: No problem, just curious.

Is there a reason this book isn’t available on Kindle?

As a resident of MD-03, let me assure you it stinks. The northern (where I grew up and my family still lives), central and southern (where I live now) parts are all radically different with very different priorities. Even through “my” team benefited, I hate it.

Not necessary. At large representation favors people with high name recognition and can require very expensive campaigns. Brazil has at large representation, and it has a VERY white Congress where more than half of the population would be considered Black, and many poor areas have no Representation on Congress. If you think that´s important that the Communist or the Libertarian Parties should (Or if you think that the US should have more than two parties) have seats on the Congress at large representation is a solution, for other kinds of minorities is a bad idea.

@SKI: There are individual districts that may be worse than yours, but the Maryland districting is probably the worst in the nation overall. It’s not simply a matter of an interest group or a few officials calling in favors, or one odd-man-out district that isn’t as elegant as the others. The whole thing is insulting.

@Andre Kenji: to clarify, I was not referring to SNTV or other majoritarian at-large systems, but rather proportional at-large systems like STV or party list proportional representation. At-large FPTP/plurality/majority constituencies (like in the Philippine Senate) are, of course, not really desirable.

Of course Brazil also has the not uncommon problem of having a very personalistic party system, somewhat reflective of caudillioism and the like, rather than a more ideological one like we see in Europe or North America.

@John D’Geek: If you mean A Different Democracy, the book is slated for an October release and should be available for the Kindle at that time.

@Chris Lawrence:

I understand the appeal of these systems. But they are not a great solution for minority representation.

Nope. Brazil has a very personalistic party system because the Brazilian Political System creates incentives for political figures to create their own small parties. Parties are extremely powerful in Brazil because they have access to public financing and because they can force votes on their members;

Besides that, the biggest distortions with Congressional Representation happens in the largest(And more urbanized) states in the Southeast, not in the Northeast where there is a real tradition of coronelismo/caudillismo.

Here in Oregon we have 5 congressional districts. One takes up 2/3 of the geographic area of the state because hardly anyone lives east of the cascades and it is solidly red. Two are clustered in the Portland Metro area because that’s where most the people live – they are solidly blue. South of the Portland area is a district that covers most of the rest of the Willamette Valley and it probably is purple but has usually gone blue the last few years because Oregon Republicans seem to insist on nominating religious fanatics or nut cases. The fifth runs from just north of Eugene down to the California border and it usually but not always goes blue simply because it includes the very blue city of Eugene.

@Ron Beasley: Oregon’s districting as far as I can tell is a good-faith effort. Some of the lines are odd, but they mostly follow the counties, and there probably isn’t a better way to do it. You’ve got three that make sense, and two that were probably labeled “Other” and had to be negotiated out.

Which is it?

@Grewgills:

That’s the point. We can talk about measures of compactness and pretend that some technocrat or computer program can produce the “right” districting scheme, but the truth is that we have competing and even contradictory criteria that have nothing to do with partisanship.

Some people don’t like bullseyes around cities, because they don’t match the municipal jurisdictions. Some people complain about pie wedges, which may match other jurisdictions but mesh groups with different demographics and political interests. Truth is, sometimes even the pinwheels and chest-popping-aliens are reasonable balances of interests and commonalities. It’s hard to tell.

@Steven L. Taylor: Yeah, sorry — that’s what I meant. It’s not available for Kindle in their pre-order section, giving the impression that it won’t be on Kindle. Thanks.