Yes, All VA Senior Executives Were ‘Fully Successful’

Lawmakers and journalists don't understand the civil service.

Lawmakers and journalists don’t understand the civil service.

NYT (“Every Senior V.A. Executive Was Rated ‘Fully Successful’ or Better Over 4 Years“):

All of the 470 senior executives at the Department of Veterans Affairs received annual ratings over the last four years indicating that they were “fully successful” in their jobs or even better, according to data released at a congressional hearing on Friday, despite delays in processing disability compensation claims and problems with veterans’ access to the department’s sprawling health care system.

None of the department’s senior executives received either of the two lowest of five possible job ratings, “minimally satisfactory” or “unsatisfactory,” in any of the past four fiscal years.

The data also showed that in 2013, nearly 80 percent of the senior executives were rated either “outstanding” or as having exceeded “fully successful” in their job performance, and that at least 65 percent of the executives received performance awards, which averaged around $9,000. Only about 20 percent received the middle of the five ratings.

Veterans Affairs officials sought to play down the data, saying that only 15 senior executives across the entire federal government had received either of the two lowest ratings in the most recent year — suggesting that the high ratings enjoyed by V.A. officials were not out of line with those of their counterparts at other government agencies.

But the data, which were a focus of a House Veterans Affairs Committee hearing, angered lawmakers who said they provided further evidence that the highest reaches of the department were out of touch with problems in the system and that there was a lack of accountability for poor management.

“Do you think that’s normal in business, that nearly every executive is successful?” Representative Phil Roe, Republican of Tennessee, asked Gina S. Farrisee, the department’s assistant secretary for human resources and administration. “That means you put the bar down here, so anybody can step over it.”

Representative Ann McLane Kuster, Democrat of New Hampshire, likened the numbers to grade inflation and said they reminded her of Garrison Keillor’s fictional Lake Wobegon, where “all of the children are above average.”

While I understand why the average NYT reader or even foreign policy tweeter would think this was some shocking revelation, it’s infuriating that Members of Congress charged with oversight of federal agencies would greet this with anything but a “Well, duh.”

Here are the five rating categories for federal civil servants:

(1) Outstanding: Work performance consistently exceeds established Performance Elements and Standards.

(2) Exceed Fully Successful: Work performance usually exceeds established Performance Elements and Standards.

(3) Fully Successful: Work performance consistently meets established Performance Elements and Standards.

(4) Minimally Successful: Work performance meets some, but not all, established Performance Elements and Standards.

(5) Unacceptable: Work performance does not meet any established Performance Elements and Standards.

Even from a casual reading, then, anything less than Fully Successful is a failure. Even for a low-level employee, much less a member of the Senior Executive Service (equivalent to military general and flag officers) a rating of Minimally Successful is highly unusual and requires extensive documentation. The vast majority of employees should expect to get Exceed Fully Successful ratings with high performers—not superstars, simply those who are above average—getting Outstanding ratings. The superstars will be distinguished from the merely above average by the written comments.

Is this inflation of the ratings rather silly? Sure. But it’s been in place for as long as I can remember.

Further, it’s simply the nature of bureaucracies to inflate ratings. While most employees, even very high performers, could use improvement in some areas of their performance, bureaucracies naturally pretend otherwise, at least officially. By definition, the “established Performance Elements and Standards” are the very minimum threshold and failing to meet it is grounds for termination.

The armed forces have a similar system and it’s even more inflated. The rating systems are replaced every few years to de-skew the process but it inevitably concentrates at the top very quickly. The Army introduced a new Officer Evaluation Report (OER) format as I was coming on active duty that tried to avoid rating inflation by rating more senior officers on the distribution of their ratings. The system—long since replaced, probably at least twice—had six “blocks.” Theoretically, the distribution for each senior rater (in my case, my boss’s boss, the lieutenant colonel commanding the battalion) should have been a bell curve, with very few lieutenants in the 1 and 6 block, more in the 2 and 5 blocks, and most in the 3 and 4 blocks. In reality—and this was a system that had only been in place for a year or two—all officers were in the top three blocks. The very top performers (say, 3 of the 17 lieutenants in the battalion) were in the 1 block. The worst of the worst (probably no more than 1 or 2 of the 17) were in the 3 block. The rest of us were in the 2 block.

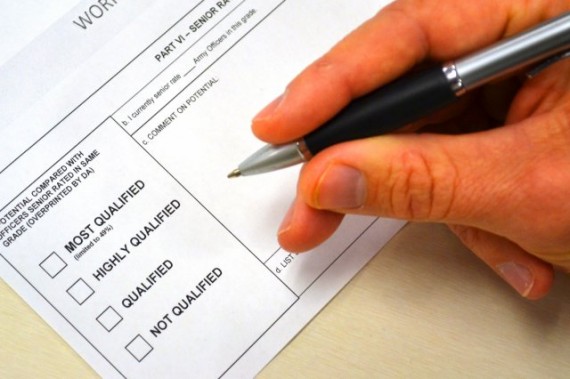

Note that in the newest version of the form, implemented last year and depicted at top, there are only four ratings categories. The top category, “Most Qualified,” is limited to 49% of rated officers!

While that may be bizarre from an outsider’s standpoint, it’s fine if the people reading the ratings understand what they’re looking at. Officers who are consistently in the 1 block should expect promotion at the earliest possible opportunity, including being picked up “below the zone” to major and lieutenant colonel. Officers who are in the 3 block, especially more than once, should expect to be separated from the service at the next selection board.

The only problem comes in cases, like my own, when officers in the vast “middle” face unusual circumstances such as a reduction in force. Normally, some 97% of the lieutenants in my year group coming up for captain would have been picked up. The 3% who weren’t would have comprised those in the 3 block on their OERs. Because of the post-Cold War drawdown, only 82% (or something like that) were selected for captain. While still quite high, of course, Big Army had to separate some of the 2 block officers and had no way to differentiate between us. That’s problematic but, again, unusual.

Similarly, if “only 15 senior executives across the entire federal government had received either of the two lowest ratings in the most recent year,” that means those ratings are reserved for the worst of the worst—if not the criminally malfeasant.

Nor is government employment unique in this regard. Companies that have employment rating systems invariably rate their employees too high, at least in terms of the names assigned to the ratings. No one wants to tell the employees that they want to keep that they’re anything less than above average. It’s not only bad for morale but socially awkward and requires a lot of documentation.

And, of course, we’ve seen “grade inflation” in academia. Whereas a “C” grade is theoretically average, in most universities and in most disciplines the overwhelming number of students get B’s and A’s—especially in the upper level courses taken by people majoring in a subject.

In all cases, the key is to operate within the system as it exists. Rating one’s employees or students based on one’s literal interpretation of the system-as-it-should be rather than the system-in-operation does them a great disservice, putting them at a competitive disadvantage.

The hard part for me to swallow is that “at least 65 percent of the executives received performance awards, which averaged around $9,000”.

Phil Roe: “Do you think that’s normal in business, that nearly every executive is successful?” Based on their termination packages, the answer to this would be “Yes”.

@Pinky:

What’s so hard to swallow about that?

@Pinky: I’m not a traditional civil servant, don’t operate under a performance award system, and so don’t have any especial insights. But, for example, bonuses were part of the standard pay package for management level employees at the Atlantic Council and not getting a bonus was exceptional. Those in the Senior Executive Service, at least those who are career employees rather than political appointees, have demonstrated themselves to be exceptional. (That doesn’t mean they haven’t Peter Principled; but SES selection is highly competitive.) There are only around 700 of them in the entire Federal Government.

SES salaries range from $120,749 to $181,500. An average bonus of $9000 is not exactly huge–it’s less than 10% of the lowest possible salary.

@Pinky: I would certainly hope the vast majority of executives at that level are competent and deserving of great rewards. Imagine if the opposite were true?

@Pinky:

I can see why the phrasing sets people off, but this is really the same thing that James was talking about. They’re called “performance awards”, but in reality they have become part of the routine compensation, as a way of partially offsetting the low (compared to private sector) salaries for career civil servants.

Here’s the OPM description of SES performance awards:

$9k is a lot closer to 5% than 20% of an SES salary, so this says most executives were getting the low end of their possible bonus — which under the current system is a worse-than-expected outcome for them. We might all agree that they shouldn’t have gotten any bonus at all — just like they shouldn’t have been rated “fully successful” — but that’s not how this Lake Wobegon rating system works.

As Anon points out above, I’m a lot less irate about this than I am about executive compensation in private industry.

@James Joyner:

This was my thought as well. It’s not much larger than my yearly bonus and I’m an hourly wage-slave, several layers below the executive level.

If a bonus is to be given, one of this size is eminently reasonable.

“Do you think that’s normal in business, that nearly every executive is successful?”

That is pretty much normal in business. If half the executives lacked the capacity to carry out their job functions, the business would be in Chapter 11.

I was fascinated to learn that in the civil service “the key is to operate within the system as it exists” and that rating one’s subordinates “based on one’s literal interpretation of the system-as-it-should be rather than the system-in-operation” thereby “putting them at a competitive disadvantage” is one of the larger sins that a supervisor can commit. That’s certainly very different from the world that I live in. But apparently government bureaucracies and other monopolies, like other empires, create their own realities, with their own through-the-looking-glass behavioral norms.

@ Pinky

As others have mentioned, why? Compared to what I am used to seeing at Fortune 500 companies, this is low. I’ve received comparable bonuses when making less than the salaries being discussed here.

I have instituted a rating system for the physicians in my practice. I send this out to other physicians in our hospital and to nurses. It is on a 1-10 scale. The average score is a 9. Even on the question where I ask them to compare with other physicians in my practice, with 5 being the average performing doc, the average score is still a 9.

Steve

@Seth K.: I’ve worked at a lot of different places—military, state government, federal government, private sector, nonprofit sector—and all of them have systems in place. It’s perfectly fine for 95 percent of the employees to get “Walks on Water” or above ratings if the people making decisions about retention, promotions, bonuses, raises, and so forth understand how the system works. Presumably, the 5 percent who get below “Walks on Water” are counseled and soon out the door if they don’t improve drastically and the true superstars are in the top category—whatever its called—or otherwise distinguishable by the use of specific buzzwords in their review.

In such a system, a manager who rates their average employees “Average” are doing both those employees and the company a disservice. Eventually, his superiors will figure out that he’s a dolt. But, in the meantime, good people are being punished for his doltishness. And the true top performers under his management won’t be promoted, hurting both them and the firm.

@James Joyner:

When language is corrupted other forms of corruption are more likely to occur. When an organization becomes heavily focused on how resources are allocated within it, its relationships with individuals and organizations outside of it – with whether, say, the veterans who depend on it for their healthcare services are, in fact, being provided with a quality product – recede into the background. When the organization must compete with other organizations for business, such things will, in the long run, come back to bite it. However, when the organization enjoys a literal or de facto monopoly, there is no built-in “reality check” to push it towards re-evaluating the way it goes about its business.