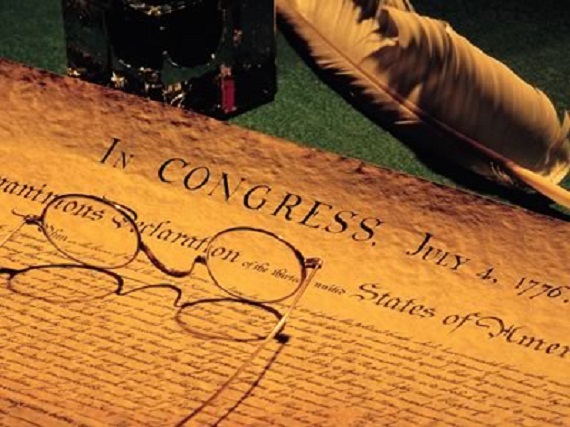

A Typo in the Declaration of Independence?

Could a transcription error be changing our understanding of America's founding document?

Could a transcription error be changing our understanding of America’s founding document?

NYT (“If Only Thomas Jefferson Could Settle the Issue - A Period Is Questioned in the Declaration of Independence“):

A scholar is now saying that the official transcript of the document produced by theNational Archives and Records Administration contains a significant error — smack in the middle of the sentence beginning “We hold these truths to be self-evident,” no less.

The error, according to Danielle Allen, a professor at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, N.J., concerns a period that appears right after the phrase “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness” in the transcript, but almost certainly not, she maintains, on the badly faded parchment original.

That errant spot of ink, she believes, makes a difference, contributing to what she calls a “routine but serious misunderstanding” of the document.

The period creates the impression that the list of self-evident truths ends with the right to “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness,” she says. But as intended by Thomas Jefferson, she argues, what comes next is just as important: the essential role of governments — “instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed” — in securing those rights.

“The logic of the sentence moves from the value of individual rights to the importance of government as a tool for protecting those rights,” Ms. Allen said. “You lose that connection when the period gets added.”

Correcting the punctuation, if indeed it is wrong, is unlikely to quell the never-ending debates about the deeper meaning of the Declaration of Independence. But scholars who have reviewed Ms. Allen’s research say she has raised a serious question.

“Are the parts about the importance of government part of one cumulative argument, or — as Americans have tended to read the document — subordinate to ‘life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness’?” said Jack Rakove, a historian at Stanford and a member of the National Archives’ Founding Fathers Advisory Committee. “You could make the argument without the punctuation, but clarifying it would help.”

Ms. Allen first wondered about the period two years ago, while researching her book “Our Declaration: A Reading of the Declaration of Independence in Defense of Equality,” published last week by Liveright. The period does not appear on the other known versions produced with Congressional oversight in 1776, or for that matter in most major 20th-century scholarly books on the document. So what was it doing in the National Archives’ transcription?

Ms. Allen wrote to the archives in 2012 raising the question, and received a response saying its researchers would look into the matter, followed by silence.

But over the past several months, she has quietly enlisted a number of scholars and manuscript experts in what the historian Joseph J. Ellis, who supports her efforts to open the question, wryly called “the battle of the period.”

And now the archives, after a meeting last month with Ms. Allen, says it is weighing changes to its online presentation of the Declaration of Independence.

“We want to take advantage of this possible new discovery,” William A. Mayer, the archives’ executive for research services, said in an email.

A discussion of ways to safely re-examine the badly deteriorated parchment, he added, is now “a top priority.”

That parchment, created in late July 1776 and credited to the hand ofTimothy Matlack, is visible to anyone. Last year, more than a million people lined up to see the document at the National Archives Museum in Washington, where it is kept in a bulletproof glass case filled with stabilizing argon gas that is lowered each evening into an underground vault.

But that document has faded almost to the point of illegibility, leaving scholars to look to other versions from 1776 to determine the “original” text.

And there, Ms. Allen argues, while those versions show subtle variations in punctuation and capitalization, the founders’ intent is clear: no period after “pursuit of happiness.”

The period does not appear in Jefferson’s so-called original rough draft (held in the Library of Congress), or in the broadside that Congress ordered from the Philadelphia printer John Dunlap on July 4. It also does not appear in the version that was copied into Congress’s official records, known as its “corrected journal,” in mid-July.

According to historical records, the Matlack parchment was signed on Aug. 2 after being compared with official texts — making it unlikely, Ms. Allen argues, that it would have contained a period after “pursuit of happiness.”

Defenders of the period are not without ammunition. The mark does appear in some official and unofficial early printings, including the broadside that Congress commissioned from the Baltimore printer Mary Katherine Goddard in January 1777, for distribution to the states.

Most fatefully, it also clearly appears on the 1823 copperplate created by the engraver William Stone to replicate the original parchment, which was already fading. The copperplate, which Stone took three years to create, has long been presumed to be a precise copy and has become the basis for most modern reproductions, including the one that has appeared every July 4 since 1922 in The New York Times.

I can’t tell much from Jefferson’s rough draft; it’s too small in the reproduction and has too many cross-outs and line edits. Additionally, the Germanic style of the day—in which all manner of nouns that we don’t capitalize today were capitalized in the middle of sentences, makes the issue more challenging.

Regardless, however, I’m not sure that I buy Allen’s argument. Jefferson was a representative of the small government line of thinking of his days, juxtaposed against Alexander Hamilton, John Adams, and others who wanted something more akin to the British strong government. But I’ve always read the section in question as declaring the Enlightenment principles that,

1. Men have certain rights under natural law;

2. That life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness were the foremost of these rights;

3. That government may not abrogate these rights (absent legitimate criminal prosecution);

4. That government is instituted to protect these rights.

I’m not sure how a period changes that conception.

The Declaration builds from the social contract theory most famously articulated by Thomas Hobbes. In his version, government had to be all-powerful in order to ensure the protection of man’s natural rights.

The American founders had the advantage of another century-plus of political philosophy from Enlightenment thinkers and had a softer, more nuanced view of the nature of the contract. But none of them—certainly not Jefferson—would have argued that government was anything but an essential tool for preserving the rights of the people. The cartoonish notion that we should have essentially no government would have been laughed out of Independence Hall.

Neither am I.

“The cartoonish notion that we should have essentially no government would have been laughed out of Independence Hall.”

Clearly, you have not read many libertarian thinkers. The notion is hardly “cartoonish” to them.

I looked at a blown-up picture of the rough draft, there is clearly a semi-colon after “happiness”, as a matter of fact, Jefferson used semicolons to separate several of the clauses in that sentence. There is a semicolon after “inalienable rights”, and another one after “consent of the governed”. A period doesn’t come until several lines later. So really that entire section is one huge sentence with several clauses.

I still don’t know that it affects the meaning in any way.

@OzarkHillbilly: Agree. Seems a distinction without a difference.

As a left of center individual I must admit that the libertarian philosophy has a certain charm but at the same time I am wise enough to realize it doesn’t really work when so many people are living so close together in a complex society.

I heard there’s a treasure map on the back!

I too really can’t see how it changes anything. There’s so many other writings by the Founding Fathers that to take a meaning from only one document or quote seems silly. Yet I see people doing it all the time.

@beth:

Not a map…but a cipher…“Just another clue, that will lead you to another clue and to another one”

No matter…the 5 activist Republican Justices on the SCOTUS are going to interpret the document any way they want anyway.

Yea I don’t see how the period changes anything at all.

I think the author of the piece is trying to project their own beliefs on the Founders via a supposed typo.

Use of punctuation has changed radically since the 18th century, and it wasn’t standardized then. Trying to read subtle distinctions into the punctuation reminds me of genealogists who argue about the correct spelling of names back then, as if there were such a thing.

Besides, you don’t need punctuation to understand the structure of the argument, because Jefferson cleverly introduces each of the “self-evident truths” with the word that:

@James:

Are you thinking of Hobbes in that second sentence? Locke’s version of government under the contract was not all-powerful, and Locke himself even allowed for the right of rebellion, which the Declaration also built off of.

Indeed, the following makes me think you are conflating Hobbes and Locke:

Hobbes published Leviathan in 1651, but Locke’s Second Treatise in 1689.

(Not that this changes your basic point).

@Doug Mataconis:

Just one more instanse of peoples who wryte good trying to impos theyre eleet views on the rest of us. Damn libruls.

Count me as another one who thinks this “period” issue is pointless.

@PD Shaw:

Heh,

The notes to the version published at the front of the United States Code Annotated say:

Sounds like Jefferson’s original intent might have been one run-on sentence.

@Steven L. Taylor: Yes; fixed! I even looked up the date of The Leviathan to make sure of my chronology. The error likely stems from having in my mind that the Declaration is more influenced by Locke—and Thomas Paine—than the original Hobbesian construct.

The Declaration is more influenced by John Locke (Two Treatises of Government):

Locke needs better punctuation, but he gives the reason for the American Colonies to rebel — their natural rights have not been protected. If you assume Jefferson was summarizing Locke, then you wouldn’t be confused by any missing period.

@James Joyner: @PD Shaw: Yes, that was I meant: that the Declaration was more influenced by Locke, but that the harsh version of contract theory was Hobbes’.

@PD Shaw: It took 12 posts, but someone finally won the thread.