Microsoft Co-Founder Paul Allen Dies At 65

One of the people most responsible for the personal computer revolution has passed away at the far-too-young age of 65.

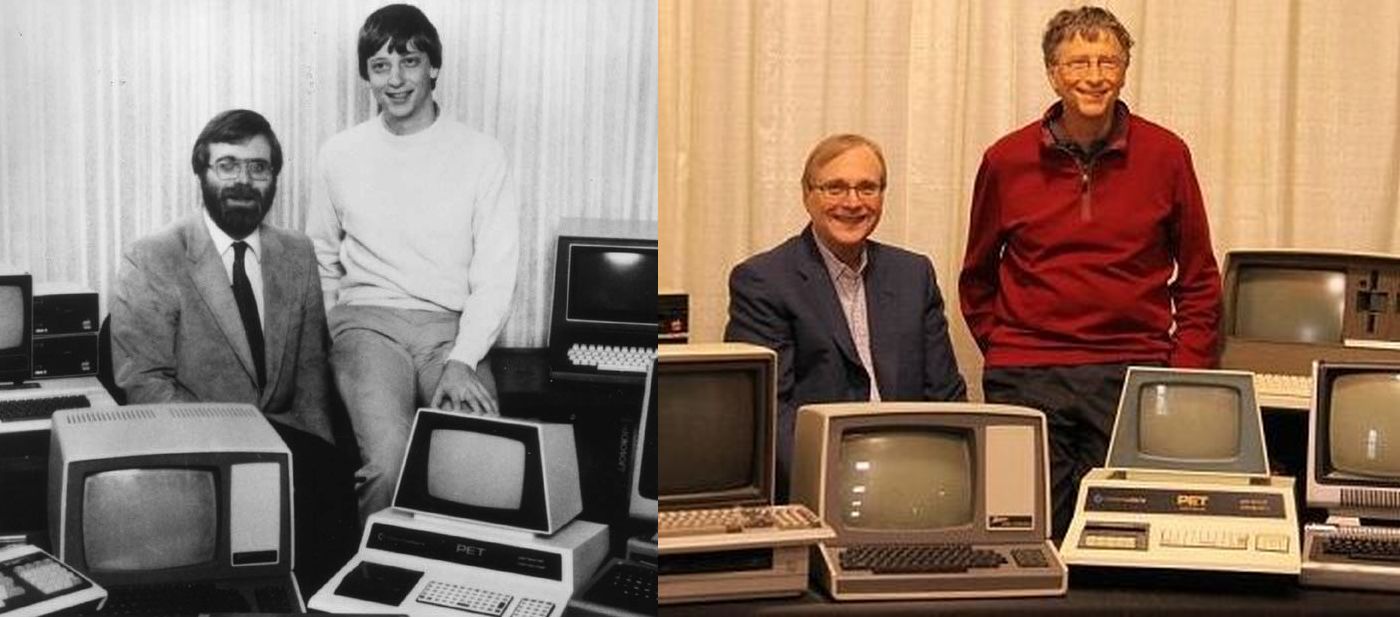

Paul Allen, who co-founded Microsoft with close friend Bill Gates, has died at the age of 65:

Paul G. Allen, the co-founder of Microsoft who helped usher in the personal computing revolution and then channeled his enormous fortune into transforming Seattle into a cultural destination, died on Monday in Seattle. He was 65.

The cause was complications of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, his family said in a statement.

The disease recurred recently after having been in remission for years. He left Microsoft in the early 1980s, after the cancer first appeared, and, using his enormous wealth, went on to make a powerful impact on Seattle life through his philanthropy and his ownership of the N.F.L. team there, ensuring that it would remain in the city.

Mr. Allen was a force at Microsoft during its first seven years, along with its co-founder, Bill Gates, as the personal computer was moving from a hobbyist curiosity to a mainstream technology, used by both businesses and consumers.

When the company was founded, in 1975, the machines were known as microcomputers, to distinguish the desktop computers from the hulking machines of the day. Mr. Allen came up with the name Micro-Soft, an apt one for a company that made software for small computers. The term personal computer would become commonplace later.

The company’s first product was a much-compressed version of the Basic programming language, designed to suit those underpowered machines. Yet the company’s big move came when it promised the computer giant IBM that it would deliver the operating system software for IBM’s entry into the personal computer business. Mr. Gates and Mr. Allen committed to supplying that software in 1980.

At the time, it was a promise without a product. But Mr. Allen was instrumental in putting together a deal to buy an early operating system from a programmer in Seattle. He and Mr. Gates tweaked and massaged the code, and it became the operating system that guided the IBM personal computer, introduced in 1981.

That product, called Microsoft Disk Operating System, or MS-DOS, was a watershed for the company. Later would come Microsoft’s immensely popular Windows operating system, designed to be used with a computer mouse and onscreen icons — point-and-click computing rather than typed commands. The company would also produce the Office productivity programs for word processing, spreadsheets and presentations.

“In his own quiet and persistent way, he created magical products, experiences and institutions, and in doing so, he changed the world,” Satya Nadella, Microsoft’s current chief executive, said of Mr. Allen in a statement.

Mr. Allen’s partnership with Mr. Gates began when they were teenagers attending the private Lakeside School in Seattle. It was there that they got their start in computing, working from a school Teletype terminal that was linked to a far-away mainframe computer under a so-called time-sharing computer system, in which operators paid for the computing time they used. Funds for the system were originally supplied by proceeds from a school bake sale.

Mr. Allen scored a perfect 1,600 on his SAT test, and went on to Washington State University. But after two years he dropped out to work as a programmer for Honeywell in Boston. Mr. Gates was nearby, attending Harvard University.

When an early microcomputer was introduced, appearing on the cover of Popular Electronics magazine, Mr. Allen persuaded Mr. Gates to drop out of Harvard and move to Albuquerque, where a start-up called MITS had built a machine that has been credited as the first personal computer. The machine lacked software, and Mr. Allen and Mr. Gates, showing up at the MITS offices, promised that they could supply it.

Their first offering was Microsoft Basic. Both Mr. Gates and Mr. Allen were skilled code creators, but Mr. Gates was more the hard-charging, volatile businessman, while Mr. Allen played the peacemaker and negotiator in those early days.

Within a few years, Microsoft moved from New Mexico to suburban Seattle. Though Mr. Allen stepped away from daily duties at Microsoft in the early 1980s, partly because of a deteriorating relationship with Mr. Gates, he remained on the Microsoft board until 2000.

Mr. Allen left Microsoft after he learned he had Hodgkin’s lymphoma. But tensions had also flared with both Mr. Gates and Steven A. Ballmer, a close lieutenant who eventually succeeded Mr. Gates as chief executive. In his 2011 memoir, “Idea Man,” Mr. Allen recalled overhearing the two talk about reducing his stake in the company.

“They were bemoaning my recent lack of production and discussing how they might dilute my Microsoft equity by issuing options to themselves and other shareholders,” Mr. Allen wrote.

But Mr. Allen held his ground and his shares.

Mr. Gates said in a statement on Monday: “From our early days together at Lakeside School, through our partnership in the creation of Microsoft, to some of our joint philanthropic projects over the years, Paul was a true partner and dear friend. Personal computing would not have existed without him.”

As Microsoft became the dominant personal computer software company, Mr. Allen, as well as Mr. Gates, who was the face of the company, became immensely wealthy. According to the Bloomberg Billionaires Index, he had a net worth of $26.1 billion.

He was also an investor and a generous philanthropist.

Mr. Allen donated more than $2 billion toward nonprofit groups dedicated to the advancement of science, technology, education, the environment and the arts. Among the scientific research organizations he funded were the Allen Institute for Brain Science in 2003 and the Allen Institute for Artificial Intelligence in 2014.

And while some of his philanthropy was global, like a passion for ending elephant poaching, much of his post-Microsoft work centered on Seattle, where he became a transformative force behind many of the city’s leading cultural institutions.

He restored the old Cinerama movie theater to modern standards seemingly ideal for watching science-fiction films, and he hired Frank Gehry to design the Museum of Pop Culture, which Mr. Allen founded in 2000 under the original name of the Experience Music Project. The wild, undulating building displayed items revealing Mr. Allen’s cultural obsessions, including guitars owned by Jimi Hendrix and Captain Kirk’s command chair from the 1960s television series “Star Trek.”

(…)

Mr. Allen also used his wealth to acquire the Portland Trail Blazers of the National Basketball Association in 1988 and the Seattle Seahawks of the National Football League in 1996.

Of all his investments, the ownership of professional sports teams was among the most incongruous. Sports owners, like it or not, are often in the spotlight, and Mr. Allen, by and large, had preferred to steer clear of media attention.

Yet in 1988, at 35, he bought the Trail Blazers and promised to keep the franchise in the city, one of the smallest in the league. He often flew to games from Seattle and sat courtside with his mother. Soon after he bought the team, the Trail Blazers had one of their best runs in franchise history, making it to the N.B.A. finals twice in three years, losing both times.

In a statement, Adam Silver, the N.B.A. commissioner, called Mr. Allen “the ultimate trail blazer — in business, philanthropy and in sports.” Mr. Silver said Mr. Allen, one of the longest-tenured owners in the league, was particularly interested in the league’s growth internationally and its embrace of new technologies.

In the mid-1990s, the owner of Mr. Allen’s hometown Seahawks, Ken Behring, was considering moving the team to Los Angeles because he was unable to get public funding for a new stadium in Seattle. Mr. Allen was urged to step in to keep the team in Seattle. In 1996, he bought an exclusive option to purchase the team from Mr. Behring by July 1997, an option he ultimately exercised, buying the team for $194 million.

Mr. Allen set about building the team a new home downtown. The team moved into CenturyLink Field in 2002, and Mr. Allen spent hundreds of millions of dollars to upgrade the stadium. Though he spoke infrequently to the media, he could often be seen at games, sometimes raising the “12” flag — representing the fans — before kickoff, a team ritual.

During his tenure the Seahawks made their only three Super Bowl appearances, winning the title once, in 2014.

“I personally valued Paul’s advice on subjects ranging from collective bargaining to bringing technology to our game,” Roger Goodell, the N.F.L. Commissioner, said in a statement.

One of Allen’s companies also owned a stake in the Seattle Sounders, one of the most successful franchises in Major League Soccer. The Sounders won the league title in 2016.

It is unclear what will happen to Mr. Allen’s teams; the details of his estate are not public. The Seahawks alone are worth an estimated $2.58 billion. Few N.F.L. and N.B.A. clubs change hands, so any sale is likely to attract substantial bids.

More from The Washington Post:

Paul Gardner Allen was born in Seattle on Jan. 21, 1953. His mother was a schoolteacher, and his father was a librarian at the nearby University of Washington. Both parents encouraged a love of reading that led Paul to engross himself in the Tom Swift series of science-fiction books, which described once-improbable inventions such as the portable movie camera and electric locomotive.

Mr. Allen’s favorite device, however, was the computer, which he began tinkering with for the first time while in 10th grade at the private Lakeside School, where a mothers’ club installed a Teletype terminal linked to a distant mainframe.

“The Teletype made a terrific racket, a mix of low humming, the Gatling gun of the paper-tape punch, and the ka-chacko-whack of the printer keys,” he recalled in his memoir. “The room’s walls and ceiling were lined with white corkboard for soundproofing. But though it was noisy and slow, a dumb remote terminal with no display screen or lowercase letters, the ASR-33 was also state-of- the-art. I was transfixed. I sensed that you could do things with this machine.”

Mr. Allen fell in with a few other tech-savvy students, including Gates, who quickly became a business partner. The two earned money devising a computerized class-scheduling system for Lakeside, and started a short-lived company, Traf-O-Data, to sell custom computers to traffic departments as an analytical tool.]

They were teenage computer geeks, bespectacled kids from Seattle who taught themselves programming from a Teletype terminal, learned the basics of business from Fortune magazine and dreamed of “a computer in every home and on every desk.”

Paul Allen was the self-described “idea man,” the shy son of librarians. Bill Gates was the business-oriented partner who brought the ideas to life. And in 1975, when Mr. Allen was 22 and Gates was 19, the friends formed a company that became known as Microsoft and unleashed a personal-computer revolution that made both men fabulously wealthy.

Mr. Allen left the company after only eight years, amid a bout with Hodgkin’s disease and a deteriorating friendship with Gates. But he remained a powerful force in technology and philanthropy for decades, investing his billions in an eclectic array of businesses and charitable efforts while acquiring sports teams, discovering World War II shipwrecks and backing aerospace ventures that drew on his childhood fascination with adventure stories and science fiction.

Paul Gardner Allen was born in Seattle on Jan. 21, 1953. His mother was a schoolteacher, and his father was a librarian at the nearby University of Washington. Both parents encouraged a love of reading that led Paul to engross himself in the Tom Swift series of science-fiction books, which described once-improbable inventions such as the portable movie camera and electric locomotive.

Mr. Allen’s favorite device, however, was the computer, which he began tinkering with for the first time while in 10th grade at the private Lakeside School, where a mothers’ club installed a Teletype terminal linked to a distant mainframe.

“The Teletype made a terrific racket, a mix of low humming, the Gatling gun of the paper-tape punch, and the ka-chacko-whack of the printer keys,” he recalled in his memoir. “The room’s walls and ceiling were lined with white corkboard for soundproofing. But though it was noisy and slow, a dumb remote terminal with no display screen or lowercase letters, the ASR-33 was also state-of- the-art. I was transfixed. I sensed that you could do things with this machine.”

Mr. Allen fell in with a few other tech-savvy students, including Gates, who quickly became a business partner. The two earned money devising a computerized class-scheduling system for Lakeside, and started a short-lived company, Traf-O-Data, to sell custom computers to traffic departments as an analytical tool.

They continued to work together while Mr. Allen studied at Washington State University in Pullman. When Gates moved to the Boston area in 1974 to study at Harvard, Mr. Allen joined him, dropping out of school to work as a computer programmer for the manufacturing conglomerate Honeywell. At the same time, he was trying to convince Gates that they should design software for personal computers — an idea that seemed far-fetched until December 1974, when Mr. Allen came across a copy of Popular Electronics at a newsstand in Harvard Square. On the cover was a picture of the Altair 8800, effectively the world’s first personal computer.

Mr. Allen, according to a 1994 account in the New Yorker, purchased the magazine and hurried over to Gates’s dorm. “Look!” he told Gates. “It’s going to happen! I told you this was going to happen! And we’re going to miss it!”

The mail-order computer needed a programming language to make it accessible to ordinary users. Mr. Allen and Gates, bluffing, told Altair’s manufacturers they had already developed such a product, based on the programming language BASIC. They created it in eight weeks, and Mr. Allen flew to Albuquerque to successfully pitch the software to the Altair’s manufacturer, MITS. To demonstrate that it worked, he typed “PRINT 2 + 2.” The machine printed a single character: “4.”

Mr. Allen and Gates considered calling their business Allen & Gates before deciding it sounded too much like a law firm, and they settled on Micro-Soft. They later dropped the hyphen, and in 1979 moved their company from Albuquerque to Bellevue, a Seattle suburb. Gates, who ultimately dropped out of Harvard, insisted on a 60-40 split of the profits before upping his share to 64-36 after the company made its first sale, according to Mr. Allen’s memoir.

“Our management style was a little loose in the beginning,” Mr. Allen told Fortune. “We both took part in every decision, and it’s hard to remember who did what.” Gates focused more on the business side, getting help from his lawyer father in drawing up contracts; Mr. Allen’s primary interest was in developing new products.

As Microsoft grew to several dozen employees, working with clients including Ricoh and Texas Instruments, it caught the attention of IBM. In 1980, it approached Mr. Allen and Gates about developing an operating system for a first-of-its kind product, the IBM Personal Computer, for launch the following year.

Rather than develop something on their own, Microsoft acquired a product known as QDOS (Quick and Dirty Operating System) from Seattle Computer. Mr. Allen concealed the fact that Microsoft planned to license the product to IBM, and he bought the software on the cheap, for $50,000. It went on to be used in millions of IBM PCs and in millions more clones, establishing Microsoft as the world’s leading software creator.

Mr. Allen was traveling in Europe, meeting with potential Microsoft clients in 1982, when he fell ill and was diagnosed with Hodgkin’s lymphoma. He spent about two years away from the company, traveling with his family and undergoing radiation therapy, before recovering from the disease and deciding he wanted to do something different.

He went on to found organizations including Interval Research, a $100 million lab designed to find the next big thing in technology, and invest in companies such as Ticketmaster.

In Seattle, he established the Experience Music Project — a music museum that grew to include a science-fiction hall of fame and is now known as the Museum of Pop Culture, or MoPOP — as well as museums for World War II-era aircraft and early computers, and a new stadium for the Seahawks and Sounders. He also developed an entire neighborhood north of downtown, which now serves as the headquarters for Amazon.

Mr. Allen was sued for sexual harassment in 1998, when Abbie Phillips, a former business partner, said she was fired after rejecting his sexual advances two years earlier. He denied the harassment and retaliation allegations, saying Phillips had resigned after being accused of embezzling company funds, and the suit was thrown out by a Los Angeles judge.

For many years, he lived on a six-acre compound on the Seattle suburb of Mercer Island, where his mother and sister also had homes. A complete list of survivors was not immediately available.

Mr. Allen served on the Microsoft board until 2000, when he and Gates’s former business manager — Steve Ballmer — was named the company’s chief executive. By then, he and Gates had reconciled, and their company’s success had gone far beyond anything the founders had ever envisioned.

In a 2011 interview with the Guardian, he recalled one early conversation with Gates, from around 1974: “We said, ‘Hey, if we’re really successful we could form a company that could grow to around 35 employees.’ Microsoft is today north of 90,000 employees. So obviously we blew through our initial hopes and dreams there.”

Bill Gates released the following statement:

“I am heartbroken by the passing of one of my oldest and dearest friends, Paul Allen. From our early days together at Lakeside School, through our partnership in the creation of Microsoft, to some of our joint philanthropic projects over the years, Paul was a true partner and dear friend. Personal computing would not have existed without him.

“But Paul wasn’t content with starting one company. He channeled his intellect and compassion into a second act focused on improving people’s lives and strengthening communities in Seattle and around the world. He was fond of saying, ‘If it has the potential to do good, then we should do it.’ That’s the kind of person he was.

“Paul loved life and those around him, and we all cherished him in return. He deserved much more time, but his contributions to the world of technology and philanthropy will live on for generations to come. I will miss him tremendously.”

Along with Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak, Allen and Bill Gates are arguably among the people most responsible for the personal computer revolution that began in the mid-1970s with hobbyists such as them to become the core of the American and world economy in roughly thirty years. Much like Wozniak, Allen was the side of the Allen-Gates partnership that was, at least initially, focused primarily on product creation while Jobs and Gates slowly began to shift their focus to business development. Eventually, both left the companies they helped found, although for different reasons, and went on to pursue other interests while retaining their ownership interest in the respective company, something that made both men immensely wealthy.

In Allen’s case, of course, it was his efforts to convince Gates to drop out of college and join the computer revolution he saw occurring when he first saw that Altair computer on a magazine cover. That successful effort proved to be pivotal, of course, because it led to the developments that brought us to the first true personal computer, the IBM Personal Computer, and an operating system that allowed it to function even for people who didn’t have the technical expertise to develop code or work with more complicated machine languages. From there, of course, the rest is history.

One of a select fraternity of whom it can be said truly left their mark on the trajectory of history.

He also replaced an entire neighborhood that was a barely used warehouse district with a massive, non-exactly vibrant mix of office park, cookie cutter apartments and overpriced mediocre restaurants.

South Lake Union is a soulless, unpleasant neighborhood now, but a big step up from a bunch of mostly unused warehouses in the center of the city. In time, it may become a pleasant neighborhood — it hasn’t had time to grow organically away from the plan.

Amazon is currently headquartered there, Google is moving in, Facebook is around the corner, and a whole bunch of smaller tech companies. Apartment buildings are being built as fast as they can, and restaurants in the area have leases requiring them to stay open well into the evening as if it was a real neighborhood — all in an effort to make it become a real neighborhood. It has also displaced a lot of homeless people, drug dealers, drug users…

It’s the largest, fastest transformation of a city that I have seen. It’s absolutely fascinating. And it was one of his hobbies.