Old Soldiers Fading Away

NYT — Old Soldiers, Fading Away at a Grim Pace [RSS]

The roughly 4.3 million who remain from the original 16 million World War II veterans are dying at the rate of about 1,200 a day, along with 300 from the Korean War and 200 from the Vietnam era. Their remains are arriving at cemeteries like the Brig. Gen. William C. Doyle Veterans Memorial Cemetery here in numbers that are expected to continue to grow until the daily losses peak in 2008, according to Veterans Affairs estimates.

In the four years that Stephen G. Abel, a retired Army colonel, has run the cemetery, it has buried as few as 10 and as many as 22 on each working day. And not only World War II veterans like Mr. Janse. On Wednesday, Specialist Philip Ian Spakosky, of Browns Mills, N.J., became the seventh casualty of the Iraq war to be buried here, the 778th fatality of that conflict. Mr. Janse, a retired tugboat captain, was 88 when he died; Mr. Spakosky, 25.

“Imagine the worst weather in the last four years, the worst snowstorm, the worst rain,” Colonel Abel said. “We were open.”

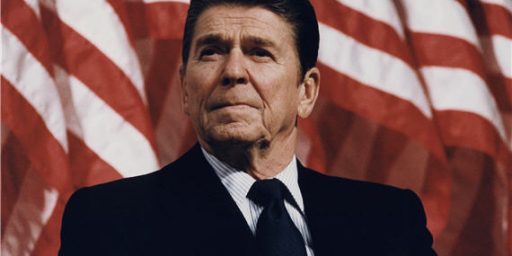

So the country will put out its flags on Memorial Day on Monday, and old soldiers by the hundreds will gather for the dedication this weekend of the National World War II Memorial in Washington.

But the toll of the years, of accidents or failing health, will not pause for the veterans’ cemeteries like this one, where 30,000 veterans and a smaller number of spouses have been buried since it opened in 1986, most of them in graves two coffins deep and half an inch apart, in a procession choreographed with the precision of a military march.

Robert E. Mullin Sr., who fought in the China-India-Burma campaign, was buried on Monday, along with six other World War II veterans that day. Natale J. Marchesi Jr., who earned a Purple Heart in the slog from the Normandy landing to the Rhineland, was buried on Tuesday. Noble C. Bryant, who also made the landing at Normandy 60 years ago, came here on Wednesday. And so on, 27 World War II veterans in all by the end of the week, men who did not survive to the 60th anniversary of the Normandy landing, which is coming up next week.

***

But the burials that veterans receive here do not resemble the kind in the movies, with mourners standing by the grave site as the coffin is lowered into the ground, pallbearers and a 21-gun salute. Colonel Abel runs four funerals an hour — two on the hour, two on the half-hour — and mourners are never allowed by the grave because there are too many burials and there is too little room to allow so many corteges to work their way into and out of the park.

Instead, mourners leave the coffin in the little chapel, or in one of the outdoor “commitment shelters,” like the one where Mr. Kennedy and Mr. O’Brien said goodbye to Frank Janse. After the mourners are gone, a little garden utility truck takes the coffin to the grave, where a backhoe lowers it into the ground.

Even the graves are predug. The cemetery has installed 9,700 concrete grave liners, most of them two coffins deep, and covered them with soil and sod. When it is time to open a new grave, the thin layer of sod is scraped off, and the liner’s lid is removed to receive the coffin.

Nor are there traditional crosses marking the graves, as there are at American military cemeteries in Europe, or “rounds,” the little rounded tombstones that are familiar to visitors of Arlington National Cemetery. Instead, the Doyle uses flat grave markers that make it easier to mow the grass.

***

“We are the ones who help people through one of the most emotional days of their lives,” he said. “We have to be helpful and sensitive, but we also have to make sure things keep working smoothly.”

For other veterans, for those who have outlived their families, the last ride to the cemetery can be a picture of aching loneliness. Even Mr. Janse, who had been a member of Lodge 107 for 46 years, left his friends, Mr. Kennedy and Mr. O’Brien, mystified by the heroism reflected in his two Soldier’s Medals, which are awarded for bravery at personal risk, normally for a life-saving effort.

Most old warriors would brag about their medals, Mr. Kennedy said, especially after the years and the beers began to take their toll on the truth.

“We found these medals in his apartment, but he never said a word about being a hero,” Mr. Kennedy said. “He was just another legionnaire.”

It’s not news that men in their 80s die. Indeed, few of them would have dreamed they would make it this long when they were slogging through the muck in 1944, as the life expectancy for men was only 61 even when they weren’t facing machine gun fire. Still, this is a sad ending.