The College Admissions Rat Race

An interesting argument, albeit about a tiny and vastly over-discussed segment.

In his New Yorker essay “The Pointless End of Legacy Admissions,” Matt Feeney seems to have shouldered the Sisyphean burden of defending the indefensible. But, really, he’s not so much arguing the virtues of allowing mediocre rich kids into good colleges but the absurdity of the admissions rat race.

His intro frames the ostensible topic in a way I’ve never quite thought about it before:

At élite colleges, there was a time when a brainy boy, one from a humble or upstart family, admitted thanks to his manifest talents, gained social status and career advantage by association with his high-born classmates—the ones whose dads and granddads had gone to the school, the legacies. Now, in a time of stem dominance and crypto-finance, a legacy kid at an élite school gains social status and career advantage by association with the smart kids. Back in the old days, the rich kids probably liked having a few smart kids from the lower classes around, or at least conceded that they were necessary. The raw bookishness of the smart kids ratified the larger enterprise that they were all participating in—it was a college, after all. But now that the aristocrats are siphoning status from the meritocrats, the social bargain is starting to look like a bad one. What are the non-legacies getting out of it? The presence on campus of posh loafers with family connections must feel like an insult to them, given their steely commitment to the college-admissions quest.

But he soon shifts, slightly, to his actual topic:

One philosophical reason to lament the end of legacy admissions is that it’s another symptom of the institutional convergence at work in American higher education. The consideration given to legacy families is a lineal gesture, and represents one of the final emblems of qualitative distinction among schools—the regional, religious, pedagogical, and historical differences that once gave America’s many colleges their many different personalities. As long as the numbers of legacy admits were decorously low, and as long as the stakes of admission to one college over another did not feature as an emergency in American society, an old college admitting a handful of underachieving legacies went with the equable assumption that an old college was a quirky thing. The number of people who gave a damn about who got into Amherst, or Swarthmore, or Bowdoin was small enough that those schools could get away with being themselves. But now those schools compete in a fully nationalized college market, under the hot light of the college-ranking industry and the obsessive gaze of the nation’s college aspirants.

Now, the nationalization of collegiate admissions is not exactly a new phenomenon. The US News ranking system began as a marketing gimmick way back in 1983, when I was a high school junior (and dinosaurs roamed the earth). But I think it true that, back then, few gave a damn about the Amhersts and Bowdoins of the world, with the nationalization limited to the Ivies, the service academies, and maybe Notre Dame.

After quite a bit of discussion about the strategic-public relations advantages of ending legacy admissions (which Amherst has done) Feeney explains,

Yet whenever a major reform is announced from within the admissions world, it’s a good idea to ask yourself what new powers the admissions department has given itself. Just as high-profile moves by colleges such as Amherst typically boost their competitive standing, the “reforms” pursued by the admissions departments of those schools reliably increase the influence of those departments, which I’ve written about in several outlets, including this one. In this case, putting an end to legacy preferences will also remove a small but obvious limit to the selection prerogatives of admissions personnel. According to the Times, citing McGann, the Amherst admissions department applies its legacy preference only after it has narrowed down its pool to applicants who are “qualified.” This contradicts the stereotype of the dim legacy, but it accords with recent data that suggest that, on hard measures such as G.P.A. and SAT scores, those admitted as legacies already fit within the larger pool of qualified applicants. This means that, for most legacies, the benefit they receive works within the softer, holistic section of the college application. Having an alumni parent is less like magically winning several hundred SAT points and more like writing an essay that the assistant dean really admired. Accordingly, the legacies will be replaced not by a clearly smarter bunch of applicants but by ones who were better at getting the admissions readers to like them. This prerogative—the enforcement power over not just academic standards but character traits and moral beliefs—is very important to the admissions departments of selective schools. Removing the legacy preference will expand it.

If this is an argument for legacy admissions, “Well, they’re not really all that much dumber than other admits” is a rather poor one. But, if it’s an argument for the absurdity of the selection system, “Why are we spending so much energy sorting which of the very-talented applicant pool at a given school is admitted?” is a strong point.

Finally, Feeney more-or-less takes us there:

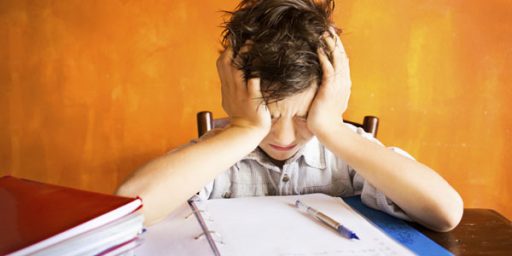

Of course, the legacy preference is still unfair, even understood in these terms. It still has a whiff of corruption about it. But, as such, it represents the corruption of an absurd process. Admissions departments have faced an intensifying selection problem over the last thirty years. As competitive behavior among college applicants grew more intense and self-aware, starting in the early nineties, it quickly became a feedback loop, with high-achieving teen-agers striving to outdo each other on both academic and extracurricular measures. To hedge their bets in this stiff competition, these teen-agers, who were better informed than past generations about both college rankings and the preferences of their fellow-applicants, applied to more schools and became more purely brand-conscious in their ambitions: they widened their focus to the whole nation and increasingly trained their sights on the best school that they could get into.

Desirable schools were swamped with eager and qualified applicants from around the country; it was both an obvious bonanza and a headache. These institutions suddenly had too many fully qualified applicants who, on paper, looked too much alike.

And this is true. Now, for the absolutely most prestigious schools—Harvard, Yale, Princeton, Berkley, MIT, and the like—one at least gets the outrage. The difference between going to one of those and, say, Bowdoin or Boston College, can be tremendous in terms of networking and barriers to entry to graduate school and certain highly competitive fields. But, really, should we care who gets into second-tier snooty private schools?

I’m somewhat less persuaded, though, by Feeney’s corollary argument: that we’re likely to substitute legacy admits for something perhaps more pernicious.

Colleges have sought to solve this problem by inventing an evolving set of moral tests and character preferences for applicants to satisfy. But it’s easy to game these criteria with gilded résumés and ingratiating, professionally coached essays—a problem that the admissions bureaucracy has addressed by declaring a new and deeper interest in “authentic” applicants. This move, though, merely gives applicants and their essay coaches a new moral trait to perform: authenticity. This—admissions bureaucrats bidding applicants to perform authenticity for them—is why Amherst’s announcement should trigger a cynical laugh. In celebrating the end of this specific corruption, we help legitimatize the larger absurdity.

This could easily be read as a critique that the Admissions Gods are too woke. But I actually agree with Feeney’s larger point: the holistic approach, while ostensibly a means of ensuring smart, creative kids from hard-knock backgrounds get a fair shot against the well-off kids whose parents can afford to sponsor expensive extracurriculars and standardized test coaching, is actually incredibly arbitrary. And, yes, by definition gives a huge amount of power to the people who assess these essays.

Ending legacy preferences really will (purportedly) remove this one bit of unfairness, and, for that, it deserves a cheer or two, but I’m inclined to begrudge it anyway. It will only strengthen the moral presumptions behind the invasive methods of holistic admissions. And it will continue the larger charade in which élite colleges use various forms of egalitarian P.R. to launder the monumental increases in wealth and cultural power that they have accrued as a result of America’s transformation into a more precarious, unequal, and atomized society built upon a white-collar “knowledge economy.” The decisive stage of this long transformation came in the early nineties, when politicians and economists declared that the smart response to disappearing jobs was for everyone to go to college. Today, thirty years later, you can watch selfie videos of anxious college applicants awaiting their admissions decisions, then collapsing into tears at the rejections or exulting in the acceptances, and feel the awesome power that these changes have bestowed upon élite colleges via their admissions procedures.

Now, again, “everyone go to college” isn’t an ethic that sprang from the ether in the early nineties. It was certainly the prevailing wisdom when I went to school—in ruralish Alabama, no less—half a decade earlier. I’d say it started with the post-World War II GI Bill and achieved full steam by the 1960s, when enrollment in college generated a deferment from being drafted to fight in Vietnam. But, then, aside for the aforementioned pull of the truly elite schools, most of the college-bound just went to very good state and regional schools.

In its growing complexity and elaboration, the admissions process appears to impressionable teen-agers as a rational and exhaustive investigation into their objective merits. But in the spiritualized meaning and methods that the colleges attach to it, and in the powerful hints of arbitrariness that attend such obscure distinctions among basically identical applicants, and in the belief that the admissions envelope or e-mail contains a message from the Fates themselves, the drama of selective admissions takes on aspects of pagan religion. After all their academic grinding and strategic self-presentation, those kids are waiting for a coin flipped by a god to stop spinning on the floor. You can see how their response in such a fateful moment, when the choice goes their way, might be swooning gratitude for the two things together—the deserved flattery by the rational procedure and the private gift from the fickle gods, who could so easily have picked a different kid. And you can see how, for kids so flattered and fate-kissed, this gratitude might later take the form of generosity—alumni donations for the élite colleges that chose them.

I don’t think Feeney does his argument any favors by continually circling back to the unproven—and likely unprovable—charge that this is some dastardly ploy by schools to increase donations. Most of the schools in question, after all, already have absurdly large endowments. But I agree that the rat race has put too much pressure on kids and parents, some of whom start trying to set their kids up for eventual success as early as pre-kindergarten.

Now, of course, everyone doesn’t participate in this process. Indeed, relatively few do.

My wife and I both have doctorates from flagship R1 universities (Delaware and Alabama, respectively). While both are selective institutions, they’re not of the sort described in Feeney’s and so many other essays in places like the New Yorker. My oldest step-daughter recently graduated Temple, where she went on a full academic scholarship. My stepson is, for a variety of reasons, at the local junior college and we expect he’ll transition next year to a solid but not particularly competitive state school here in Virginia. My youngest step-daughter is a freshman at George Mason, a very good and somewhat selective school that happens to be a 20-minute drive from our house. My daughters, currently in 7th and 5th grade, are a ways away from college decisions but I suspect they’ll attend state schools in Virginia unless they’re competitive for truly elite schools elsewhere. (And, even then, it’s not like Virginia and William and Mary aren’t top-tier.)

Even at that level, though, there’s pressure. Mason was the “safety school” for several of my step-daughter’s high school classmates and there was some competitive angst about not getting into W&M. But her current plan is to be an elementary school teacher after graduation. There’s really no reason to sweat over institutional prestige for that and most other lines of work.

As to the nominal issue of legacy admissions, I’m rather agnostic. At the hypercompetitive schools—the Harvards and Yales of the world—it’s really hard to find a positive. Otherwise, though, there’s something to be said for family traditions and having junior attend the college where Mom and Dad met and whose teams they grew up rooting for. While it’s not really an ambition of mine, I would be perfectly happy to have my daughters go to Alabama (which is frankly a much more competitive school to get into than it was when I went) and experience the tradition there. So long as they’re qualified to get in, I don’t see much harm in my having graduated from the institution weighing in their favor.

When we were in StL, we lived in a neighborhood across the road from Washington Univ. I’d regularly walk the dogs on campus (both of whom had developed relationships with students that stopped to pet them and give a treat when walking by). Usually I’d pick up the school paper to see what was going on there, the incoming freshman issue one year struck me. The lead article began to the effect, we know you are disappointed to be coming here, you really wanted to go to Brown, Cornell or Columbia, but now you are here… The piece went on to talk about it’s not where you go, but what you make of yourself from being there. Yeah the college admissions rat race makes no sense.

Perhaps the answer is for the colleges to set a minimum objective criteria and have a lottery of those qualified. This would eliminate the subjective process of trying to rank by merit.

Why the flying fuck does The New Yorker insist on slapping on unnecessary diacritical marks on perfectly cromulent fully understood English words.

Elite does not need an acute diacritical for fucks’ sakes. Grr! They do the same shit with cooperation. They add an umlaut. God damn morons. This isn’t 1450. These words have entered English centuries ago and are universally understood and have a common pronunciation. Why would anyone in 2021 America put an acute above the first e in “elite”? That’s just fucking stupid.

It is just so fucking pretentious. And I used to subscribe to the New Yorker.

Their stylebook is just so much crap.

Is this actually true though? Most of the big names in tech aren’t generally the smartest people in their classes, but rather the most well capitalized people in their classes. The real value of a Havard education isn’t that it’s a better school from an education standpoint, but rather that it provides access to an unparalleled networking opportunity.

@de stijl:

It may be annoying in most cases, but I feel like putting an entirely unnecessary diacritical on the word “elite” is entirely appropriate.

@de stijl: @Stormy Dragon: I tend to think of the élite spelling as a signifier that one should pronounce it AY-lete, unlike the plebes who pronounce it EE-lete. But, yes, it may simply be a style guide thing.

@Stormy Dragon:

If it were a brand new borrowed word maybe it might make a tiny bit of sense kinda sorta.

But “elite”? That is a stupid hill to die on.

A fucking stupid and pretentious affectation.

I eventually stumbled on the right word for this bullshit – affectation. A pose. We are smarter than you.

Smart people know that “elite” is commonly used in everyday English. Leet 1337. We get it. This is not decades after the Norman invasion. It is a French loan word. Tell me more.

The priggish affectation nonsense of it is very off-putting to me.

There is absolutely no goddamn fucking reason in the world at all to put a fucking acute above the first e in “elite” in a 2021 American publication. Doing so makes you a dick.

A small point, but did the rich kids really feel the smart kids lent credibility? Or was it that they needed someone to crib from?

NBC reported recently that 43% of white students admitted to Harvard were legacy, recruited athletes, children of faculty and staff, or “dean’s interest” (kin of donors). That does seem excessive.

@gVOR08:

I was never of that class but would imagine a George W. Bush liked being able to say he went to Yale and Harvard Business, not simply because they signaled his elite status but because those brands have the association with high intellect that came from so many non-blueblood smarties getting in.

@de stijl:

Perhaps my point was not clear: I find the accute mark in elite ironically funny, because it fits the stereotype of someone going overboard trying to “act” elite and instead just looking silly and undermining their effort. So in a way that, say, “coöperate” does not, “élite” adds an additional layer of subtext that I find hilarious, particularly in the context of a New Yorker article.

Basically, I’m arguing that an “elite college” and an “élite college” are two different things, the former being actually elite and the later only appearing to be elite.

@de stijl: “They do the same shit with cooperation. They add an umlaut.”

Not an umlaut, actually. A diaeresis.

Thought you’d want to know.

@Stormy Dragon:

We are on the same page. No worries.

I was just letting my profane rant flow and used your reply as a diving board. (It was fun, btw. I enjoyed myself.)

No offense or disrespect intended at all.

—

It is fun and a bit cathartic to get pissed off and vent about a meaningless thing. The New Yorker stylebook is very far down the list of things that irk me, but it was a convenient target. My anger is real but shallow.

And it is such a stupid thing; just spell elite and cooperate like a normal person. You are making this weird on purpose with your style choice.

It is a distracting affectation that adds absolutely nothing.

@wr:

I enjoyed that. I deserved it.

Made me laugh.

And it would also eliminate the cherished notion that I/my child is getting something that I/my child deserves to have (hence the notion that these choices are meritocratic. I don’t expect that particular dodo to fly very far.

For my take, the best explanation came from an essay that I read either in The Atlantic or Harper’s where the essay subject was speculating that the most significant problem for the future is that our society simply has more elites (and people who imagine themselves to be) than there are opportunities available for elites. Not a problem that I foresee resolving itself any time soon. Granting new admissions to the elite by lottery is not likely to resonate well with either the elites or the institutions–which, except for those at the very top, could suffer backlash from “just letting anyone in.”

@James Joyner: Or the even less than plebes, who pronounce it “uh-lete.”

“Doing so makes you a dick.”

Now I’m confused. We were talking about The New Yorker, right? If you’re not going to be a pretentious dick there, where else do you have?

@Just nutha ignint cracker: Ha. I read it EElete and say it UHlete or even uhLETE depending on context.

@Just nutha ignint cracker:

Possibly The New York Review of Books.

@CSK: A book by the same guy may have been reviewed there, but I don’t read The New York Review of Books. Haven’t had access to it in decades.

@CSK:

I was thinking the same thing.

Seriously, The New Yorker is decidedly middle brow stuff. It is not intellectually challenging in the slightest for a person who is a bit educated. If you went to state school and majored in biology or anything really, you would have no problem at all.

This isn’t translating Cahiers du Cinema in your head on the fly level stuff. It is The Atlantic with an unearned veneer of sophistication.

NYT food critics get too fancy pants a lot. It’s food. Does it taste good?

@Sleeping Dog:

This. The college race has gotten insane. The amount they expect you to do to rise above the crowd — extracurriculars, advanced classes, volunteer work — is leaving kids with no life (and good luck if you’re a poor kid). Everyone’s blaming “screen time” and “social media” for the high stress rate among teens but with my own 14 y/o, I can see the insane amount of work she’s being given and the crazy expectations if she wants to get into an elite school. A few years ago, I had a high school intern who was crazy qualified, way better than I was and told me there was no chance she would get into an elite school.

Set a minimum standard. Say you won’t consider any extracurriculars beyond X. And everyone get a lottery ticket. Hell, give out extra ones to under-represented minorities, legacies or whatever if you want to. But the idea that there is any objective and reasonable way to distinguish between a hundred qualified applicants is lunacy.

The success rate of applicants to my alma mater is now less than 9%. Cringe. This is now ridiculous.

(I’m still convinced I got in because of my seeming world-weary unflappability during the interview. Actual fact was I was just coming off a very intense period of Japanese immersion training and my reaction was: “oh wow, someone is speaking English to me!”)