Less Than Zero

The Social Security "trust fund" may actually be worse than worthless.

Investor’s Business Daily warns us that the Social Security “trust fund” may actually be worse than worthless:

Investor’s Business Daily warns us that the Social Security “trust fund” may actually be worse than worthless:

[A]n analysis done by the Congressional Budget Office last year on the effect of high government debt levels suggests that unless the government gets its fiscal act together, the value of the trust fund is less than zero.

Under the Alternative Fiscal Scenario, which approximates current policy, CBO finds that elevated debt levels would crowd out private investment and restrain economic growth to a significant degree. Specifically, GDP would be 15% smaller in 2035 under the current policy trajectory than it would be if debt stabilizes around current levels, as it would under the baseline scenario.

While CBO assumes the current-law trajectory for Social Security under both the alternative and baseline scenarios, what matters for its crowding-out analysis is suffocating debt levels, not what contributes to the debt.

Debt would be 185% of GDP in 2035 under current policy — vs. 79% under the baseline scenario. By that point, using assumptions from Social Security’s 2010 annual report, redemptions of trust fund bonds would have raised debt levels by about 18.5% of GDP, or $4.5 trillion in 2010 dollars.

In other words, debt incurred by paying unfunded Social Security benefits would account for nearly 1/6th of the crowding-out effect, curbing GDP by about 2.6%.

In short, if we don’t rein in the federal government’s profligacy, Social Security (which is already a lousy deal for workers) will slowly strangle the country to death. Right before the so-called trust fund runs out entirely.

The slight of hand is right here:

They are talking about 2035, but saying that every dollar must come from “raising taxes” and not the “growth” that folks like Investor’s Business Daily would normally champion.

It’s a very sloppy review of a projection which itself assumes the unimaginable … that is, that we’d ride this thing, as is, to 2035.

Huh?!? Saying that the trust fund represents dollars government must be able to pay out somehow is essentially a tautology. As stated immediately before your pullquote, the “trust fund” doesn’t hold assets of value. It holds IOUs to the taxpayers to be paid by the taxpayers.

The whole point of the piece is that coming up with those dollars will decrease the size of the economy — growth will be smaller because of it. The only “sleight of hand” here is your attempt to invert logic. The dollars can’t come from “growth” if the economy will be 15% smaller because the government is sapping the productive economy of available capital.

You are coming in at a lower level there Dodd than I am speaking.

You can think about that money using a variety of accounting methods. You can imagine it as Social Security, Inc. buying government bonds, or yes you can consider it all Uncle Sam, Inc. on a cash accounting basis.

I think you are trying the Uncle Sam, Inc. accounting, but getting it wrong. On that basis it is just plain old government debt, and yes, growth and same or smaller tax rates can pay it down, without tax increase. That is, if you get the growth.

Have Steve V explain it to you.

Oh, by the way, the government also has the option of a lot of inflation and COLA (or not) games between now and 2035, to make the books work.

I look forward to Steve V. coming in and explaining why I, and IBD, are too dumb to understand your Olympian logic.

Increased tax revenue comes in part from economic growth.

^ – Dodd’s unheard-of Olympian logic.

And we’ll get that without reining in debt by generous application of Handwavium despite a 15% smaller economy from crowding out. Pretty Olympian.

Can you explain this “crowding out” idea?

Normally, crowding out happens as a result of spending, not social security style debt:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Crowding_out_(economics)

IBD kind of turns that on its head, doesn’t it? They claim that more treasury buyers, which should drive more people out of treasuries, and to private investment, somehow crowds out.

I don’t see it.

(If anything, the fact that SS might, in their capacity “bid low” decreases my odds of buying treasuries and increases my odds of owning other instruments.

Don’t tell me you think the SS trust fund is out there reaming Treasury for high rates.)

Dodd … um…. did you read the actual CBO report?

Because this scenario described by IBD is what happens if the Bush tax cuts are extended indefinitely.

According to the same report, if taxes return to Clinton-era rates, this scenario is avoided.

If I recall correctly, you argued in favor of extending the Bush tax cuts.

Um, yeah, no. The piece quite plainly discusses the increased spending represented by paying off the trust fund IOUs. Is everything the opposite with you today?

Indeed I did. Because the problem isn’t revenue; it’s spending. Raising taxes, even if it were conceivable that Congress would limit itself to what it takes in, won’t solve it. We could also revert to 2008 spending levels (which wouldn’t be nearly enough; there’s plenty of fat in Bush’s profligacy to roll back, too) and more than solve the problem. The notion that the extra trillion we’re spending each year now compared to 3 years ago is absolutely vital and cannot be unwound is laughable.

Yes, yes, I know. You deny that higher tax rates harm economic growth. I don’t buy it. Static analysis of the two tax schemes, as if economic behaviour won’t change if we revert, is patently absurd.

I’m just curious…if raising taxes is off the table concerning balancing the budget, if this should be done only through spending cuts, exactly what things adding up to a trillion dollars can be cut, realistically, that is…

That is something that is often said, but is incomplete. The CBO baseline scenario assumes all the Bush and Obama tax cuts expire (ie. we return to Clinton tax rates) but it also assumes the Medicare “doc fix” is actually implemented, the AMT fixes are allowed to expire, and finally that discretionary spending does not increase faster than inflation.

Look, there are lots of rational ways to warn on Social Security, and to note that if “all else remains the same” for the next 24 years, there will be trouble.

But this construction does not seem like one of them.

It is sort of like “if there is failure” (no change to social security) “then there will be failure” (it will all hit the fan.”

Well yeah, and still a pretty screwy way to describe the fan-hitting.

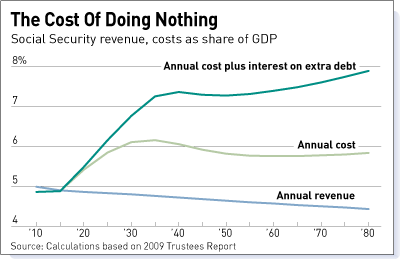

that IBD article is quite a perversion of what the CBO report actually said…and that chart isnt a CBO chart; it was made up out of whole cloth…

> Because the problem isn’t revenue; it’s spending.

And here is where reason and real world leave the building and dogma takes over.

“You deny that higher tax rates harm economic growth.” – it’s not just commenters denying it, but history.

That’s because the system is gamed to support government spending: