American Maximalism

Stephen Sestanovich [RSS], President Clinton’s ambassador to the former Soviet Union from 1997-2001, has an interesting op-ed in today’s NYT:

As Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice leaves today for a fence-mending swing through Europe, many Europeans have seized on her experience working for President Bush’s father as a reason to hope that she will revive a pragmatic, nonideological, less unilateral foreign policy. They forget what the diplomacy of the first Bush administration was really like. In dealing with the biggest European security issue raised by the end of the cold war – German unification – the United States opposed the major European powers (other than Germany, of course), ignored their views, got its way, and gave them almost nothing in return. In “Germany Unified and Europe Transformed,” her much-praised history of this period, Dr. Rice made clear that American policy was not based on consensus-building and respectful give-and-take. Her experience, she said, taught her the importance of pursuing “optimal goals even if they seem at the time politically infeasible.” She considered single-mindedness as the key to diplomatic success: a government that “knows what it wants” can usually get it.

Is this just memoir braggadocio? Not at all. When the Berlin Wall fell, European leaders hated the idea of German unity. François Mitterrand told President Bush it would lead to war. Margaret Thatcher and Mikhail Gorbachev proposed a peculiar scheme to keep a united Germany in both NATO and the Warsaw Pact. But the bloody historical experiences behind such views didn’t sway Mr. Bush. If others didn’t trust the Germans, that was their problem, not his. Washington favored unification and wanted to achieve it as quickly as possible. In particular, American officials hoped for the rapid dismantlement of the East German state – a prospect our allies viewed with horror. Robert Zoellick, then the State Department official responsible for German policy and now Dr. Rice’s deputy-to-be, recalled that once the United States decided to accelerate the process, it encouraged the East German public to demand immediate unification and to vote out leaders who favored gradualism.

[…]

In the end, President Bush and his advisers made no real adjustments to conciliate worried allies. The memoirs of Mrs. Thatcher, Mr. Gorbachev and Mr. Mitterrand are shot through with frustration over how Washington kept them divided.

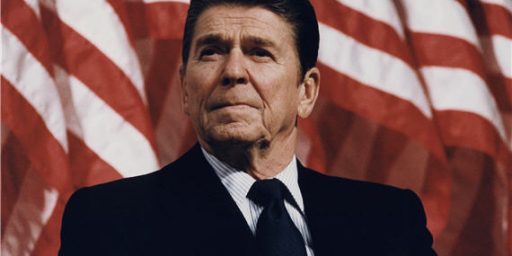

What explains this high-handedness? The Bush administration believed what most recent administrations have believed: our allies were shortsighted and confused, and not tough-minded enough to achieve lasting success on a large scale. This was Ronald Reagan’s view when he scrapped détente. It was Bill Clinton’s view when he abandoned the policy of “containing” genocide in the Balkans. And it was Madeleine Albright’s view when she explained what she meant in calling the United States an “indispensable” nation: “We see further than other countries into the future.”

Certainly true. The reason is one of perspective, not brilliance. The United States, alone among the world’s states, has truly global interests. We focus on the big picture, not because we’re particularly magnanimous or farsighted but because our sphere of interest demands it. The UK, perhaps because it is the most recent country to be a truly global power, is the only one that comes closest to our outlook. Germany, France, Russia, China, and others are major countries whose counsel should be taken. But their interests and vision is simply much more localized than ours.

I have always been of the school of thought that the million dollar question is, what happens when China’s concerns stop being local and start being global. One could argue that that has already taken place but really they still have a way to go. Perhaps I have been unrealistic believing in the slightest potential for China to influence the U.S. in the future, economically and diplomatically. Perhaps the likelihood of that occurring isn’t so great as the ‘theoretical’ schematics indicate.

Perhaps I am something of an alarmist. Perhaps I should start a subdomain for others recovering from this fear, and call it Fear of Chinese World Domination Anonymous ( FCWDA ). Perhaps it could work as a support group for others suffering from the same concerns.

I don’t know where this idea of Chinese world domination comes from, but most likely from the era of the yellow peril. For its entire history, China has been an inward looking country. It considers itself the center of the universe and everyone else as barbarians. This attitude continues, though at a somewhat more modest scale than during the imperial era. China today is only interested in maintaining its national boundary (including Taiwan) and securing good relations with its neighbors. Now, what constitutes good relations is up for debate. There’s no argument here that China would like to dominate her neighbors, but not actually run them directly. She’s not likely to come across the Pacific any time soon.

I’m well aware of Chinese culture. Chinese economic pressure seeking to dominate the world is a popular economic theory, I’d love to pull out the ref.s for you. But maybe some other day.

p.s. seriously, do I need to pull out the ref.s?

It’s just a theory, right? The Lenovo deal scares some Americans but business is business, and IBM was glad to get rid of its notebook division while it was still worth something. If it’s good for the US to dominate the world, who’s to say it isn’t just as okay for China or India someday to have their day in the sun?

yes, just a theory, very debated, extensively debated. the thing is, if china were to get that great of economic influence over the US, what is to say that that wouldn’t reach over into a domestic policy influence. basicly the potential for a slacking of international concern for human rights and basic freedom could possibly come into question. but it’s all theory

That theory would assume a politically statist China. If political liberalization and reform comes hand in hand with economic development, who knows what China will look like in 50 years? Maybe it will look along the lines of what Taiwan is like today. My guess is as good as theirs.