Bill Frist Political Fund Can’t Cover Bank Loan

Frist Political Fund Can’t Cover Bank Loan (WaPo, A02)

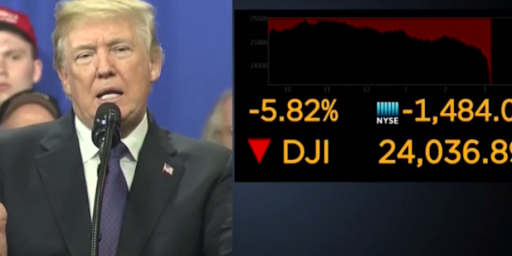

A campaign fund controlled by Senate Majority Leader Bill Frist (R-Tenn.) has lost almost $460,000 in stock market investments since 2000 and now does not have enough to cover a sizable bank loan, according to federal election records and the manager of the Frist account. The heaviest losses, totaling more than $500,000, occurred in a stock index fund in 2001 and 2002, years when the securities markets suffered a major downturn. But the Frist campaign account lost an additional $32,050 in July and August, a setback that was only partially offset by a gain of $11,472 in September, according to Linus Castignani, treasurer of “Frist 2000,” which was created to finance the senator’s successful campaign for a second six-year term in 2000.

Democrats yesterday seized on the reports of the losses, which were revealed by the Chattanooga Times Free Press. Todd Webster, spokesman for outgoing Senate Minority Leader Thomas A. Daschle (D-S.D.), said in an e-mailed statement that the losses raised questions about a Republican plan to let Americans invest a portion of their Social Security contributions in the stock market. “He still thinks we should put seniors’ Social Security funds in the stock market?!” Webster said. In a departure from Senate protocol, Frist journeyed to South Dakota this fall to campaign for Daschle’s opponent, John Thune (R), who narrowly won the election.

This is embarrasing for Frist, to be sure, but it obviously has little to do with the advisability of Social Security reform. It’s not as if workers invest their money and withdraw it all a few months later. Even if one retired at the beginning of a historic stock market crash, such as in 1929 or 1987, the gains made over the course of an entire working life would be greater than under the current system. And, of course, one would draw benefits on a monthly basis, meaning that the market would recover long before the crash did any substantial damage.

Campaign finance experts said candidates are allowed to invest their war chests in the stock market, although the practice is considered somewhat unusual. “There’s nothing illegal about it,” said Larry Noble, the executive director of the Center for Responsive Politics. “The profits go into the campaign. The losses come out of the campaign.”

I must admit to being caught unaware by this one. It makes sense to put one’s surplus campaign funds into a savings account, certificates of deposit, or other short-term, low risk investments. Why would they be invested in a high risk medium, though, when they are going to be withdrawn within weeks rather than years or decades?

And, as David Wissing points out, this also raises some interesting questions with regard to income taxes and campaign finance laws.

Update: See also Steve Verdon‘s “Frist Political Fund: Follow Up.”

“Even if one retired at the beginning of a historic stock market crash, such as in 1929 or 1987, the gains made over the course of an entire working life would be greater than under the current system.”

Although, this is not necessarily true. What would happen, say, if your money was tied up in enterprises that went out of business?

I haven’t studied the privatization proposal, but if people can really determine where there money can go, obviously some people will make bad decisions. If they don’t have sound investment advice, what happens if someone “puts all of their eggs in one basket” and the basket breaks?

Kappiy, I haven’t looked at the proposal in detail, either. Any planned that could get through Congress, though, would presumably be based on some sort of index fund. And, of course, we’re likely only talking about some small portion of one’s Social Security funds being freed up for voluntary private investment, anyway.

Two percent is the number I keep hearing.