Douthat Attempts a Defense of the Electoral College

Ultimately, it isn't a very good one.

I consider the current surge in discussion about the Electoral College to be a good thing because while the chances of change in the short term are essentially non-existent, the only long term chance for change requires public awareness of the EC’s problems.

I consider the current surge in discussion about the Electoral College to be a good thing because while the chances of change in the short term are essentially non-existent, the only long term chance for change requires public awareness of the EC’s problems.

A major problem for defenders is that it is really quite difficult to generate a compelling defense of the system. Most attempts seem to be based on the intent of the Framers and the genius of its design. But, as I have noted repeatedly, it doesn’t take a lot of research to note that the process the Framers designed never worked as intended. So, even if one accepts that intent arguments are the gold standard for understanding constitutional functionality (they are not, BTW), appeals to intent have to be tossed out the the window.

Other defenses include the notion that it protects small states against large ones (this really isn’t the case) or that somehow it requires candidates to pay attention to the whole country, not specific states (which it doesn’t).

Quite frankly, the best defense I can personally conjure is: it historically has mirrored the popular vote, so why worry about it? The problem with that defense is that we are in an historical moment in which two of the last five outcomes have not worked out that way. Another defense is that by having votes contained within states you do not have any scenario in which there would be a national recount (but that strikes me more as an elections management issue, rather than a reason for the EC, per se).

Personally, from a democratic theory point of view, I would assert that any pro-EC argument has to provide a defensible reason as to why two votes, cast in the same election, should have a different value. I have yet to see such a defense.

Meanwhile, Ross Douthat has taken to the pages of the NYT to make A Case for the Electoral College.

Is there a case for a system that sometimes produces undemocratic outcomes? I think so, on two grounds. First, it creates incentives for political parties and candidates to seek supermajorities rather than just playing for 50.1 percent, because the latter play is a losing one more often than in a popular-vote presidential system.

Second, it creates incentives for political parties to try to break regional blocs controlled by the opposition, rather than just maximizing turnout in their own areas, because you win the presidency consistently only as a party of multiple regions and you can crack a rival party’s narrow majority by flipping a few states.

According to this — admittedly contrarian — theory, the fact that the Electoral College produces chaotic or undemocratic outcomes in moments of ideological or regional polarization is actually a helpful thing, insofar as it drives politicians and political hacks (by nature not the most creative types) to think bigger than regional blocs and 51 percent majorities.

Here’s the problem with these suppositions: parties and politicians are going to aim for the easiest to obtain goal, not the hardest. If I can win with a minority, then I am going to shoot for winning by minority (that is easier than winning by super-majority). Expanding support is harder than motivating existing support. There is also the pesky fact that the nature of voter turnout patterns in the US (as well as partisan identification) means that the best route to victory is a turning out one’s supporters, not trying to convince new voters to vote.

Also, the notion of regional blocs is pointless: no Democrat is going to win in the Deep South, for example. The focus in this system is for Democrats to ignore the South as a result and go hunting for votes in swing states. This actually deepens, therefore, the lack of attention parties play to certain locations. Why campaign somewhere a party knows it will lose (or knows it will win)?

And, of course, none of this explains why we should defend a system that counts the votes of different voters in the same contest as having different value.

Douthat’s own defense is half-hearted, as he notes:

However: This defense of occasional countermajoritarian presidencies assumes that the political system will, over the medium-term, be responsive to the Electoral College’s incentives — that parties will be capable of overcoming polarization and addressing specific regional grievances, that politicians will be capable of working toward Rooseveltian or Reaganesque majorities, that presidents who win with a popular-vote minority will either adapt and gain a majority the next time (as George W. Bush did) or lose like Benjamin Harrison and John Quincy Adams.

And neither political party has responded to 2016 the way my defense of the Electoral College predicts they should. A countermajoritarian outcome has not produced supermajoritarian ambitions. Instead of trying to expand its base, the Trump-era G.O.P. seems to be relying on the Electoral College to actively avoid any sustained outreach, while Trump’s likely Democratic rivals seem to be taking Clinton’s popular-vote margin as a license to march leftward.

To be honest, he is making up the whole virtue of countermajoritarian outcomes out of whole cloth to defend an institution that continues to be indefensible.

What’s telling is that Douthat’s half hearted and frankly borderline dishonest defense of the EC is actually one of the better ones out there.

I’ll keep saying it again and again… the Bush campaign in 2000 had a contingency plan in place to challenge the outcome of the election should Gore win the EC vote while losing the popular vote. That shows you how sincere Repubs are in the praise of the EC.

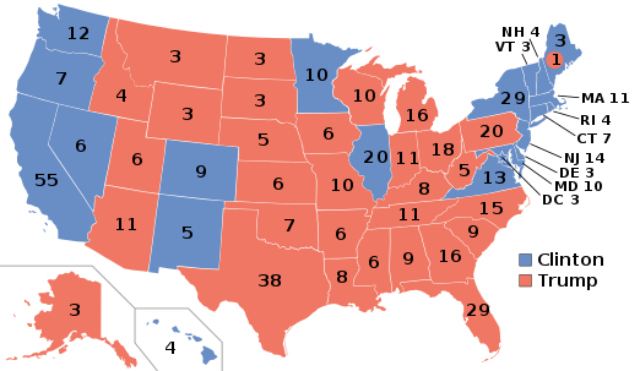

To Douthat’s point, Trump didn’t win by seeking a supermajority. He won by seeking the 50.1 percent of the voters in the states that mattered. Ever since, he has shown zero interest in expanding his voter base beyond this narrow slice of the electorate.

The fact that I have to refer to “states that matter” shows just how bad the current system is.

Not only doesn’t it require paying attention to the whole country, it does the complete opposite.

95% of the 2016 campaign’s candidate events took place in 12 states, and 66% in six states. This was actually a slight improvement over 2012, when 100% of the events took place in 12 states and 66% in four states. The nation’s three most populous states at the time–California, Texas, and New York–got zero candidate events in 2012. Zero. 35 other states were similarly ignored.

In 2016, California and Texas, combined population about 60,000,000, got one visit each.

Now, maybe some stalwart EC defender can explain how all but ignoring nearly 20% of the nation’s population equates to paying attention to the whole country.

@Paine: Trump doesn’t even pretend to be the president of all the people. He talks about California like it isn’t part of the US. It’s bad when senators and congresspeople talk like that, but POTUS doing it says a lot.

What’s really surprising about this column is that Douthat didn’t claim the electoral college does the only thing he cares about — stopping people from having sex unless it’s approved by his church.

@Paine:

Not even 50.1%. He got below an absolute majority in WI, MI, PA, AZ, NC, FL, and UT.

To my mind, the problem goes deeper than this. It’s a triumph of democracy when the slimmest of margins is no hindrance to the peaceful transition to a new government. But that cannot happen too often, especially in a highly polarized two-party country. Political stability and legitimacy depends on the ability to steer a middle course over the medium term, and to avoid deeply unpopular radical shifts in direction over the short term. We are failing here and no change in the EC will fix that.

I always have this question for EC defenders: if it’s so ideal, why aren’t you suggesting a similar system be put into place in governors’ races? Give the counties the equivalent of “electoral votes,” to give small towns some parity with the big metropolitan areas.

Nobody suggests doing that, because everyone knows it’s a stupid idea. These defenses of the EC are after-the-fact rationalizations. Republicans defend it because they know they’re the beneficiaries of it at the moment, but more broadly, the defenses all have an air of “It must have value because it’s been with us for so long.” They’re defending it because it’s there, not because they’d ever seriously design a system that way if starting from scratch.

Something I’ve wondered about … say There is no EC in 2020, and say Trump loses by 100,000 votes overall, a very small margin when 130 million votes are counted. Does he file in all states for a recount? In certain states? A guy like Trump might tie up the election result for months with recount and validation of voter roll litigation.

What a nonsensical argument from Douthat- that the system exists to encourage a candidate to seek a supermajority and if the candidate fails we will reward the other candidate who failed even worse.

Thank you Dr.Taylor. I was thinking about writing a critical comment on Douthat’s column, but I had neither the time nor the inclination to study it. And on a quick reading I couldn’t find anything that made enough sense to use as a hook.

Remember that after a long search Douthat was the best conservative writer NYT could find. Can we at some point conclude modern conservatism is indefensible?

@gVOR08:

November 8, 2016.

@Kylopod:

I saw someone arguing in Twitter that if Florida had a Electoral College Gillum would have won because the Republicans could not simply pump up the vote in the Panhandle.

@Mikey: Oh way before that. For me, it started being indefensible in the late 90s.

@Kylopod:

I do not know who you are talking too (I am guessing not people from small towns in states dominated by a huge city.) But I have often said Illinois would not be in such the mess we are now had we had a electoral college system. The reason I would not take a chunk of my life to make that happen is because of the practical impossibility of changing the status quo.

@gVOR08:

Sometimes I think that the NYTimes deliberately found the worst plausible conservative voices they could get to be “balance”.

Sadly, they were then taken seriously, and the joke is on the rest of us.

@Gustopher:

Does seem like it sometimes, Douthat and Bret Stephens both.

But I think NYT has demonstrated too many times they are obsessed with “balance”. Plus, who would you nominate instead? The names that come to my mind are either reformed conservatives, and anathema to current conservatives or reformicons who represent no actual Republicans.

@Gustopher:

Stephens is horrible, but the real issue with Douthat is that he is a pretty talented writer, but he does his best writing when he is not using the hat of “Conservative” columnist. His columns about meritocracy are pretty interesting, but he does not write them under a Conservative perspective.

@Kylopod:

But this is the very definition of conservatism. And Douthat was hired to be a conservative writer. He needs to fill out column inches so he speculates and does thought experiments, but the bottom line conservative argument for the electoral college is:

For a century and a half we have used this system and have had peaceful transitions. If it ain’t broke…

Personally, I don’t find this compelling, but it’s not nothing.

@MarkedMan:

Indeed.

Like I said:

I am very serious about this. I have spent some time actually trying to sort out the best defense (a colleague and I have contemplated some publishable material on this subject).

I honestly am at point wherein “if it ain’t broke” is the best argument, and the problem is that is appear to, in fact, be broke.