Gaddafi and the ICC: Meaningless, Unfair, or Both?

The selective application of international law is here to stay.

On the matter of the International Criminal Court arrest warrant for Muammar Gaddafi, my first thought was that it was another foolish step by the international community, which should instead be doing everything in its power to give the Libyan dictator an easy path to peaceful exile.

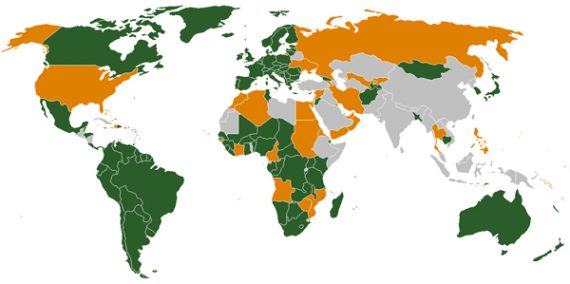

But The Atlantic’s Max Fisher (full disclosure: he’s edited the two pieces I’ve published there) argues that it really doesn’t matter. He provides this map as the jumping off point for his analysis:

The ICC relies on member states to actually perform arrests. The Hague-based court can issue all of the warrants and indictments it wants, but it only has effective jurisdiction in countries that have both signed and ratified the treaty recognizing the court and its authority. The court issued an arrest warrant in 2009 for Sudan’s President Omar al-Bashir, who today is still in office So, in practice, an ICC arrest warrant can be little more than a lifelong ban against traveling to certain countries.

This map, via Wikimedia commons, shows the ICC’s global membership. The countries in green are party to the ICC and could arrest Qaddafi; countries in orange signed but didn’t ratify the treaty and couldn’t arrest the Libyan leader for an ICC warrant. Neither could the countries in gray, which do not recognize the court.

Qaddafi, son Saif, and brutal intelligence chief Senussi will probably never again visit the green countries. The European nightclubs and art museums of which Saif was so fond will forever be off limits; Qaddafi’s jaunts across the continent he’d dreamed of leading will be much shorter. But, as long as they remain in orange and grey states, the warrants will make little difference. And the green states might not even be categorically off limits. After Bashir’s arrest warrant was issued, the Sudanese leader traveled to ICC member state Chad without issue. It’s not enough that a state recognizes the court — it also has to choose to make the arrest. Qaddafi, who had deepened his influence in Sub-Saharan African by funding many of the post-colonial revolutionary groups that later took power, could probably get away with visiting much of the continent safely.

Ultimately, Max comes down to my position, that we should make his surrender possible, but he convincingly argues that “Ultimately, the arrest warrant is likely to serve as little more than another bargaining chip in any negotiations over ending Libya’s civil war. That’s a good thing — as fighting worsens and civil society degrades, anything that makes peace more likely is essential — but it’s not quite international justice in the legal sense of the term.”

FP’s David Rothkopf makes the related point that international justice ain’t all it’s cracked up to be, noting the selective enforcement inherent in the system.

Of course, Qaddafi has every reason to be bitter. The international community singled him out and has starkly and apparently unabashedly ignored far worse violations by Bashir al Assad, to pick just the most egregious case of a double standard. Not that Qaddafi doesn’t deserve the arrest warrant issued by the ICC on Monday. Not that the world won’t be a better place when he is out of office or better, behind bars paying for his brutality, his sponsorship for terror and his myriad abuses against his own people. But, if ever a guy was having a “why me” moment, it must be him as he reads about Syrian crackdowns, recalls the Iranian crackdown, watches as leaders from North Korea to China to Myanmar to Russia to Zimbabwe to Sudan to the Congo to Venezuela order their opponents locked up or worse.

That’s the problem with the administration of international justice. It’s not that the Qaddafis and the Mladics of this world don’t deserve to end up in the slammer. It’s not that they are not getting their just desserts. It’s that justice is not applied equally around the world.

It’s that among the anachronisms of our time, far too many leaders are able to hide behind an impenetrable veil of sovereignty when they commit acts that otherwise would be seen as indefensibly illegal. Too many are able to successfully justify their actions politically and even make moral cases for their immorality. Whereas with run-of-the-mill criminals, those who cooperate with the authorities end up living under an assumed name in witness protection programs, when crimes are committed on behalf of the authorities they start out under assumed names — like self-defense or preserving order or honoring a faith or national heritage. In fact, most big time offenses actually might better be oxymoronically described as crimes on behalf of humanity.

This state of affairs is unlikely to change any time soon. Getting sovereign states–most of which are run by despots or minor autocrats–to band together on the principle that sovereign rulers ought to be constrained in their domestic policies is dicey, indeed. Even among the democratic states, there’s a longstanding distinction between SOBs and our SOBs. Bahrain, and for that matter Saudi Arabia, are given far more latitude than Libya. Indeed, even Gaddafi himself has gone from Public Enemy Number 1 to exemplar of the Bush Doctrine and back again.

Good points all. One minor correction: according to Polity and Freedom House, most sovereign states now have democratic governments.

@Jay: Fair point: The vast majority of states now qualify as “Electoral Democracies” by Freedom House standards. But only roughly a third (51) are “free,” with another third (51) “partly free” and another third (60) “unfree.”

The problem is that the Africans are complaining that only Africans are indicted by the ICC. That´s why even countries that ratified the treaty allowed Bashir to enter their countries.

I think the question is why now? Your colleague has made an argument that the move has no practical import. I would argue (as you suggest and as I implied in an earlier comment) that the move is an actual impediment. Not only does it give Gaddafi one more reason to hold on to power to his dying breath, it makes it harder for countries that are signatories to the convention to cut him a deal for a more timely exit.

I can only speculate that there’s some political motivation that’s opaque to us poor benighted Americans. Is there a constituency for this somewhere? Are Europeans that desperate to feel good about themselves?

Dave,

Yes, good question. As best I can tell, two diametrically opposed explanations are simultaneously true:

1. Europeans actually believe international law matters, whereas Americans see it as a tool for achieving policy ends.

2. Europeans think acting as if international law matters is sufficient, whereas Americans think we have to abide by the treaties we enter into and are therefore much more reluctant to enter into them, lest they impede us.