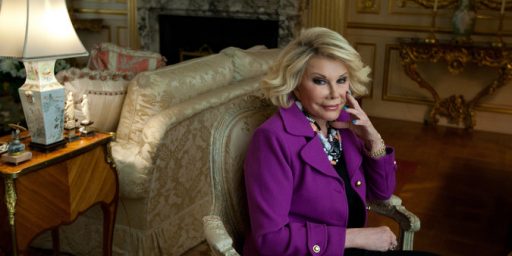

Legendary Actress Joan Fontaine Dies At 96

Joan Fontaine, who became an icon of Hollywood’s Golden Age, died yesterday at the age of 96:

Joan Fontaine, the patrician blond actress who rose to stardom as a haunted second wife in the Alfred Hitchcock film “Rebecca” in 1940 and won an Academy Award for her portrayal of a terrified newlywed in Hitchcock’s “Suspicion,” died at her home in Carmel, Calif., on Sunday. She was 96.

Her death was confirmed by her assistant, Susan Pfeiffer.

Ms. Fontaine was only 24 when she took home her Oscar in 1942, the youngest best-actress winner at the time, but her victory was equally notable because her older sister, Olivia de Havilland, was also a nominee that year. The sisters were estranged for most of their adult lives, a situation Ms. Fontaine once attributed to her having married and won an Oscar before Ms. de Havilland did.

Until the Hitchcock films, Ms. Fontaine’s movie career had not looked promising. While Ms. de Havilland was starring opposite Errol Flynn in hits like “Captain Blood” and “The Adventures of Robin Hood” and captured the coveted role of Melanie Hamilton in “Gone With the Wind,” Ms. Fontaine struggled.

In 1937 and 1938, she made 10 mostly forgettable pictures, alternating between screwball comedies like “Maid’s Night Out,” in which she starred as a socialite mistaken for a servant, and dramas like “The Man Who Found Himself,” in which she played a noble nurse determined to save a hobo’s life.

In 1939, she appeared in two critically acclaimed pictures. She was a minor player in “Gunga Din,” with Cary Grant and Douglas Fairbanks Jr., but made an impression in the all-female ensemble cast of “The Women.” Those roles were followed by her career-making performance in “Rebecca,” which Frank S. Nugent praised in The New York Times as the film’s “real surprise” and “greatest delight.”

In the 1940s and ’50s, Ms. Fontaine — only slightly typecast as shy, aristocratic or both — had a thriving movie career, starring opposite the era’s male superstars, including Burt Lancaster, Tyrone Power and James Stewart.

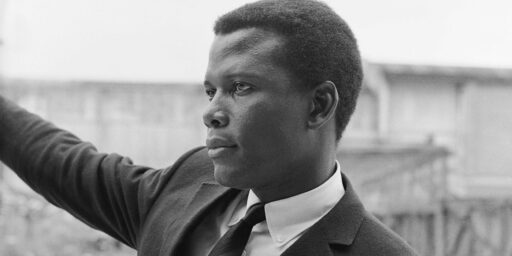

She played the title character in “Jane Eyre” (1944), opposite Orson Welles; a romantic obsessive in both “The Constant Nymph” (1943), for which she received an Oscar nomination, and Max Ophüls’s “Letter From an Unknown Woman” (1948); the prim Lady Rowena in “Ivanhoe” (1952); and a British colonial in the Caribbean in the early race-relations drama “Island in the Sun” (1957). That film’s mere suggestion of an interracial romance, between Ms. Fontaine’s character and Harry Belafonte’s, was considered daring.

She made her Broadway debut in 1954, replacing Deborah Kerr as a headmaster’s sensitive wife who helps a young man affirm his sexuality in “Tea and Sympathy.” Brooks Atkinson, writing in The New York Times, preferred Ms. Kerr but called Ms. Fontaine’s performance “forceful and thoughtful” and her New York appearance “one of the better lend-lease deals with Hollywood.”

She returned to Broadway once, in the late 1960s, replacing Julie Harris in the comedy “Forty Carats,” about a middle-aged woman’s romance with a younger man.

Joan de Beauvoir de Havilland was born to British parents on Oct. 22, 1917, in Tokyo, where her father, Walter, a cousin of the aviation pioneer Sir Geoffrey de Havilland, was working as a patent lawyer. In 1919, her mother, the former Lillian Ruse, moved with her two daughters to Saratoga, Calif., near San Francisco. The de Havillands divorced, and Lillian married George M. Fontaine, a department store executive, whose surname Joan later took as her stage name.

Ms. Fontaine, who also briefly used the name Joan Burfield (inspired by a Los Angeles street sign), moved back to Japan at 15 to live with her father and to attend the American School there. Returning in 1934, she soon moved to Los Angeles to pursue a film career.

Her final big-screen roles were the heroine’s jaded older sister in “Tender Is the Night” (1962), based on the F. Scott Fitzgerald novel, and a terrified British schoolteacher in “The Devil’s Own,” a 1966 horror film.

Ms. Fontaine married and divorced four times. Her first husband was Brian Aherne, the British-born stage and film actor, whom she married in 1939 and divorced in 1945. She married William Dozier, a film producer, in 1946, and they had a daughter. After their divorce in 1951, she was married to Collier Young, a film and television writer-producer, from 1952 to 1961, and Alfred Wright Jr., a Sports Illustrated editor, from 1964 to 1969.

In 1952, she took in a 5-year-old Peruvian girl, Martita Pareja Calderon. When the girl ran away in her teens, Ms. Fontaine was unable to bring her home because she had never formally adopted the girl in the United States.

Ms. Fontaine is survived by her sister, Ms. de Havilland; a daughter, Deborah Dozier Potter of Santa Fe, N.M.; and a grandson.

Though other actors and actresses who appeared in Alfred Hitchcock’s films received Academy Award nominations, Fontaine was the only one who ever actually won an award for her performance in “Rebecca.”

As for her sister, Olivia de Havilland is still alive at 97, and living in Paris where she has spent the last several decades. As this 2012 New York Post story notes, the two sisters didn’t exactly have the best relationship:

The sisters have carried on Hollywood’s longest-running and most bitter feud, currently in its eighth decade — clashing over roles, Oscars and lovers, among other things. They have not spoken in 35 years.

Their rivalry goes back to their childhood in Japan, where Fontaine claims the 15-month-old de Havilland “was still too young to accept the arrival of a competitor for the affections of her parents and adoring staff.” Their British-born parents split in 1919, and their mother, Lillian, took them to California because of young Joan’s poor health.

After the family resettled near San Jose, Lillian married a department store owner named George Fontaine. Both sisters hated their stepfather and his authoritarian ways, but disliked each other even more. Olivia, the editor of a school magazine, published a mock will: “I bequeath to my sister the ability to win boys’ hearts, which she does not have at present.”

When Joan was 15, in 1933, “Olivia threw me down on the poolside flagstone border, jumped on top of me and fractured my collarbone,” the younger sister recalled. “I regret I remember not one act of kindness all through my childhood.”

Both elegant beauties, the sisters were soon professional stage actresses, with de Havilland quickly zooming to stardom when she was signed by Warner Bros. and teamed with Errol Flynn in “Captain Blood,” the first of their seven films together.

Fontaine, meanwhile, struggled in forgotten B-movies before landing bland romantic roles in more ambitious movies opposite stars like Fred Astaire and Cary Grant.

Fontaine was the first to marry — to one of de Havilland’s discarded boyfriends, actor Brian Aherne. The night before the wedding, de Havilland’s beau at the time, billionaire Howard Hughes, flirted with Fontaine — something her sister was none too happy about.

But that was nothing compared to their professional rivalry. When Fontaine tested for the role of Scarlett O’Hara in “Gone With the Wind,” producer David O. Selznick asked if she would be interested in playing the sweet Melanie Hamilton instead.

To her everlasting regret, Fontaine rejected what she considered an inferior role. Instead, she suggested her sister, who snagged an Oscar nomination, for Best Supporting Actress.

Fontaine beat out her sister for the much-sought lead in Alfred Hitchcock’s “Rebecca” and received her first Best Actress nod, though she ended up losing to Ginger Rogers.

But at the 1942 Oscars, the sisters went head to head for Best Actress — the first time this ever happened — de Havilland for “Hold Back the Dawn,” and Fontaine for another Hitchcock film, “Suspicion.” Fontaine won, and things got really bad.

Fontaine recalled: “I froze. I stared across the table, where Olivia was sitting. ‘Get up there!’ she whispered commandingly. All the animus we’d felt toward each other as children . . . all came rushing back in kaleidoscopic imagery . . . I felt Olivia would spring across the table and grab me by the hair.”

Things got worse when de Havilland finally won her own Best Actress Oscar, in 1946, for “To Each His Own.” “After Olivia delivered her speech and entered the wings, I went over to congratulate her as I would have done to any winner,” Fontaine recalled. “She took one look at me, ignored my hand, clutched her Oscar and wheeled away.”

Sharp-tongued Fontaine gave as good as she got. When de Havilland wed the frequently married novelist Marcus Goodrich in 1946, Fontaine quipped, “It’s too bad that Olivia’s husband has had so many wives and only one book.” The sisters didn’t speak for six years after that, not even when de Havilland won her second Oscar for 1949’s “The Heiress.”

“This cut me to the quick,” de Havilland told Hollywood columnist Hedda Hopper in a never-aired radio interview unearthed by film historian Robert Matzen for his book “Errol and Olivia.” “I never got any kind of apology, and wasn’t going to say, ‘How do you do?’ to her until I did get it,” she added.

There were occasional truces between the sisters. But after their mother died in February 1975, the estrangement became permanent.

One imagines the hyper-competitive nature of Hollywood only enhanced what it seems to have been a long brewing example of sibling rivalry.