On the Median Voter

A David Brooks column inspires some thoughts.

David Brooks had a column the other day about the mid-term results versus recent polling concerning Trump v. Biden. It is entitled Democrats: You Can Chill Out Now! I am not going to comment on the whole thing, but the following leaped out at me (such is the way in which the clearing of tabs can take one into a lot of words).

So, here we go. From Brooks:

The median voter rule still applies. The median voter rule says parties win when they stay close to the center of the electorate. It’s one of the most boring rules in all of politics, and sometimes people on the left and the right pretend they can ignore it, but they usually end up paying a price.

The Democrats’ strong showing in elections across the country this week proves how powerful the median voter rule is, especially when it comes to the abortion issue.

Ok, there is actually a lot to unpack here and there is no way to cover it all in one post, but let me note something that I think is really important: the median voter “rule” (really, what is usually called the median voter theorem–although it is really isn’t a theorem, but more a model or theory) is highly dependent on the distribution of voters, and therefore to what the median of that distribution is*. Journalists, and often people in general who talk about such things, tend to speak as if we always have a normal distribution of voters in terms of ideology (so that the centrists are the big peak in the curve) and that is how we should understand election outcomes.

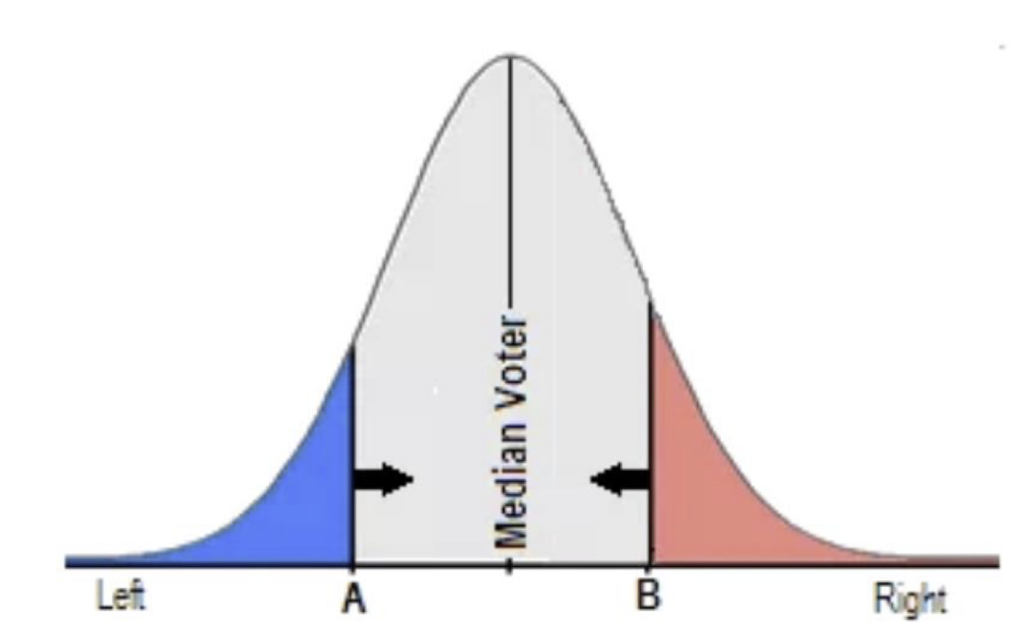

Basically, the simple model looks something like the following and assumes a vast middle with the true left and right being far smaller. Yes, this is a simplified model but it should give everyone an idea of what I am talking about. The higher the curve, the more voters at the given ideological point under that part of the curve. In this distribution there are a lot of centrists and, indeed, the center of the distribution (the median, wherein half the voters are to the right of that point and half to the left) is the Most Centrist of Centrists (which the space at which many, many, many pundits pretend like they exist and the position from which many a column pining for a Third Party Savior has been based). Logically, a far-left extremist would lose to a moderate, or even a conservative, and vice versa.

So, sure in a distribution like that, the candidate who is more centrist out of two is likely to win. And assuming that the US electorate looks like this is why columnists and third-party activists pretend like the way forward is centrism. This was the logic of Ross Perot and, to a degree, people like Joe Manchin and his No Labels (yes, it’s a label) buddies.

And frequently this is the way that people talk about American democracy as if it is just a big relatively fair contest and the competition is in (or should be in) the middle.

However, one of the various reasons that I argue that the US has a democratic deficit is because, no, it doesn’t work that way.

First, if we think about the US presidential race, the reason (well, one of them) that the Electoral College is a problem is that it skews the outcome away from whatever the median preference of all of the voters is. A national popular voter ought, in fact, to drive electoral competition to roughly wherever the actual median of the electorate is (which is not the perfect bell curve above, but for the sake of argument I will say that it isn’t radically different).** But, instead, the process drives the competition to a limited number of competitive states.

I would note that one of the reasons that national polling for the president is a problem is because, as we all know, there are actually 56 individual contests (50 states plus DC plus the two Maine and three Nebraska district-level elections). The issue becomes, therefore, not what the national median voter is, but what the median voters are in each of those elections. (By extension this is true in the 50 Senate races and 435 House races).

Second, this is why single-seat districts are a problem (which is made worse by gerrymandering). The median voter in state X might in fact be more moderate, but when you can slice state X into, say, seven segments, you can make damn sure to skew the outcome as far away from the state median towards your party as possible. And even if the state’s districts are drawn in a non-partisan way, they are very likely to skew away from the state’s overall median preference because of population distributions.

Further, most US congressional districts would have curves that would peak either substantially farther to the left or to the right than the curve above.

I would note that both the EC and the usage of single-seat districts result in where lines are drawn ending up to be more important than the actual democratic preferences of the voters. This is why they diminish democratic quality and representativeness. Again, the location of the lines ends up being more important than the broader distribution of voter preferences.

Third, I would add that primaries further skew the issue of whether the system is really driving competition to the median. The median primary voter almost certainly has a different ideological profile than the median co-partisan at the district level. But, the median district-level voter is going to vote for their party’s nominee because they are closer ideologically to them than they are to their opponent’s nominee (or, at least, their partisan ID tells them this is the case even if their district is a case of an MTG-like GOP candidate and moderate Democrat).

On that last point, I would note that partisan identity itself as a general matter influences how voters perceive candidates, meaning that it is possible that a given candidate might actually be closer to the median ideologically in a given district but that voter perception is swayed by party labels and the signals they are perceived to be sending. This is a large part of the reason why even if, say, in a heavily Republican district a moderate or even center-right Democrat who might be closer to the ideological median of the district is going to lose, despite pundit (and sometimes by OTB commenter) fantasies to the contrary.

To Brook’s point, sure, it is clear that the median position in Ohio is pro-choice, but this isn’t a good illustration of the median voter concept, because a referendum of this type is about voter preferences on one single issue, not a guess by voters of whether candidate X or Y is closer to the ideological median of a given district. Not only is that just one issue, which makes it easier to determine where median preferences lie, but the mechanism of a simple yes/no choice on a statewide ballot definitionally finds the median preference (more or less)–at least it identifies roughly where the median preference is on the exact question being asked.

Indeed, if the statewide contest for, say, Senate, had been a pro-choice Democrat and a pro-life Republican, the outcome of that contest would have been a bit different, even if abortion was THE topic of that race (but it still would only but one variable in a far more complex stew of issues and views). That illustrates in simple terms the difference between a single-issue choice and a race between candidates even with the exact same pool of voters.****

After all, Ohio was roughly +8 R in 2020 and J.D. Vance won his Senate seat in 2022 by +6.1. The abortion reference passed +13.2. As such, what this likely tells us is a lot more about abortion than it does about the appropriate application of the “median voter rule.” (Or at, least, the potential limitations of using it to find political clarity).

A side note to conclude, which opens up another can of worms. It is worth considering the degree to which we should be concerned with just having the median views of the country represented, or whether we should prefer a system that proportionally represents the entire distribution of voters. The entire discussion above more or less assumes only two choices and either plurality or majority decision rules.

*If you are at a party and 40% of the people like pepperoni pizza, 20% like sausage, 20% like a combo of both, 10% want Canadian Bacon, and 10% are vegetarian and there is a vote, it sure looks pepperoni to me. But if the distribution is 70% vegetarian, 20% pepperoni, and 10% “can’t we have hamburgers” the vote is going to be vastly different.

**This is where I note that I am writing this for funsies on a weekend and am not writing a real academic treatise. Were I doing that the figures would be much better!

***And I will risk being accused by some readers of being too pie in the sky and note that an electoral system with proportional representation, even modest PR, could solve this. This is doable for the House by legislation, depending on the system deployed. Yes, it is a political non-starter at the moment, so I probably should not even mention it!

****Note I said “pool of voters” and not just “voters” since turnout affects who the voters are, even if they all come from the same pool.

*** ???

The attractiveness of the the “median voter rule” is that it allows columnists like David Brooks to pontificate about where the median voter is at (which naturally happens to coincide with David Brooks’ policy preferences).

They’re never going to give that up. Who can resist speaking for the entire electorate (if only in their heads)?

@Mister Bluster: Me being cheeky. Someone inevitably tells me that reform is impossible and that I am being too academic or somesuch. 😉

Dang, you made me read the whole David Brooks column, and to my surprise, I found nothing to really object to. He’s made his living for decades pretending to be a moderate centrist while really being a Republican concern troll. Perhaps Trump, and DeSantis, Vance, Abbott, Pence, Haley, Hawley, Gaetz, Alito, Leo, Johnson, …., have beaten the GOP out of him. In fairness the median voter thing in the column was kind of in passing. He didn’t even make the de rigueur crack about extremists on both sides.

Didn’t Rachel Bitecofer have a thing about a negative median voter theorem? The winner is the candidate who least repels the median voter. A theory Biden seemed to have embraced in ’20 by staying bland and not triggering negative partisanship.

This remains the most important aspect of your elections that remains rather badly presented in press and in general, and even in comments it seems to me a vast majority of commentators do not truly price this in, not truly – falling into the traps of national level abstraction as to electorate, remaining fundamentally blind to the structured importance of significant geographic variation

Rather like considering if one preferentially prefers unicorns or Pegasus as you haven’t any path to achieve any kind of actionable reform in this area.

Good piece Steven. Thanks.

I guess the ‘median voters’ of Ohio rejected normalcy and went for a charlatan like J.D. Vance. Or maybe the ‘median’ curve in Ohio has shifted pretty far right.

Median voters are not necessarily much better than the so-called extremist fringe that elects people like Lauren Boebert. I mean, what is the ‘median voter’ in Marjorie Taylor Greene’s district? Is the term ‘median voter’ useful any more? I’m not sure of this at all. the ‘median voter’ is a moving target.

Ridding ourselves of the Electoral College would not necessarilly give us sunshine and rainbows, but it would be better than what we have now. That sais, it’s not going to happen.

@drj: Human nature pretty much guarantees that we will tend to see our viewpoint as being the median one unless gifted with uncanny levels of self-perception. Moreover, I wish to posit a different theory about the center and “the median voter.” Given the veritable universe of issues and options about how to resolve them, is it possible that the “quintessential median voter”–the one who supports the middle road on every issue–is not at the middle of the curve but rather on one of the edges as the ultimate outlier given that holding the median position on every issue is unlikely to be the actual behavior of the largest plurality in the cohort mix?

ETA: In the alternative, I would suggest that the curve of voter preferences is a relatively flat, kind of blocky distribution with no particularly recognizable peak at the mid point/median.

@Lounsbury: I don’t see it as a “fundamental blindness” as much as the same kind of concession that economists make in theorizing “all thing being equal.” As one of my econ professors put it in a private conversation once, yes everybody knows that all things being equal doesn’t happen in real life, but admitting this eliminates the ability to project about outcomes and causes.

They maintain the fiction to do their work–and in the modern day, to get those all-important clicks.

When I saw that bell curve of left-to-right voters, I wondered what it would look like weighted for likelihood of voting in primaries and general elections.

Wouldn’t that be 54? (Maine and Nebraska are being counted twice, as normal states, and then again as special states with silly district elections)

That’s where my head is at today, needlessly nitpicking. I’ll just skip this discussion.

@Gustopher: Nebraska equals 4 contests (1 statewide and 3 districts) and Maine is 3 (1 statewide and 2 districts).

@Steven L. Taylor: needlessly nitpicking and wrong! The perfect combination!

and

Gee, I wonder who you are talking about!

On that, I’ll just say that we all have different opinions. Your disagreements with David Brooks are not dissimilar from my disagreements with you. There is a universal desire for us all to make the points we want to make and criticize the arguments of those we disagree with, including you using Brooks’ piece to return to the issues and arguments you like to discuss in the way that you like to discuss them.

Anyway, on the median voter stuff generally, I think one of the problematic effects of our de facto binary system is how often the framing for all sorts of issues is reduced to a single axis with two poles (or arguably a horseshoe) where all things must inevitably fall somewhere on that axis, hence why we tend to use words like “average” and “median” as descriptors for people who are not orbiting one of the two poles.

The problem, of course, is that real people in the real world, as well as events and policies, do not neatly map on an American-centric partisan or left-right axis. We’ve seen, for example, how the conflict between Israel and Hamas does not neatly map on this axis. There is a real diversity of viewpoints.

Similarly, the “median voter” is also not a single thing IMO. It’s a shorthand for everyone and everything that doesn’t neatly map to one side or the other. This includes those who are genuinely “in the middle” between the two poles on any issue, but it also includes those who are cross-pressured, those who see little difference between the two sides on issues they care about, those who don’t have strong opinions or are disengaged, and those with political preferences and policy views that do not exist on that simplistic axis.

My view is that this “middle” group of voters and Americans, have been decisive in national elections recently because those elections have been close (again, by “close” I’m talking about the system as it is, not as one might wish it to be).

I think our political class, particularly people like Brooks, as well as campaigns that actually want to win, need to do a better job of trying to suss out what’s going on with this group of “middle” voters, particularly those who live in the key swing states that are likely to decide the election. This is where nationalized data (such as the aggregate state of the economy) can be deceptive. Averages and medians can hide a lot of variability.

@Andy: You are right that no voter will be at the median across multiple issues. IIRC there’s a theorem that where a population has positions on multiple issues there isn’t an optimum position for a politician to take. A Pareto maximum can’t be defined.

But, it turns out that a single axis works fairly well. There’s a procedure called NOMINATE that ranks politicians based on their votes. Turns out that if Senator A is left of Senator B on issue 1, there are good odds he’s to the left on issues 2, 3, 4,… However, they sometimes add a second dimension for a particular issue, say civil rights. They could, I guess, do any number of dimensions, but one still offers a pretty good approximation.

Which, sort of, doesn’t matter because voters don’t vote on policy anyway, they vote on some weird tribal identity. (Although policy can influence where they see a candidate’s tribal membership.) Those who aren’t locked into a tribe vote more on feels than policy.

I’m writing this quickly, without looking anything up, so I have no problem if Dr. T wants to correct me on terminology or concept.

@Steven: The combination of your concluding side note and first asterisk is noteworthy. To wit:

Ideally, depending on how many guests there are, rather than ordering a sufficient number of pepperoni pizzas to satisfy the majority, we’d get a proportional number of pizzas satisfying all of these desires. But, if we’re forced to order only one pizza for all, it’s rather clear to me that vegetarian would be the winner because otherwise that group can’t eat at all whereas the others will just be marginally grumpy about the tastiness of their dinner.

@James Joyner: Ideally, indeed.

@Andy:

You, of course, but not just you.

Regardless, I would argue that in your comment you are, despite semi-rejecting the concept, making the typical argument about centrist/swing/etc. voters.

And note that part of my point is that the concept is used too simplistically in the discourse.

But my main point is that even the basic notion of the median voter is different in Mississippi than it is in Vermont, in terms of ideology. It is certainly different in a Congressional district that is 75% R versus one that is 75% D. It really isn’t all about centrist and swing voter even thought it is inevitably treated as such (indeed, Brooks does in his column, and I think you are in your comment).

And, further, to your point (and to mine in the post), if we are able to reduce it to single issues (like abortion) then you can get a more accurate understanding of the median position on that topic. But when candidates run then there is a vast mixture of issues and partisan cues tend to take over.

This is why the centrist columnist’s dream of the socially liberal, fiscally conservative candidate never works.

And, I will note as I have before, the true swing voter (which is not necessarily the median voter) is often not especially ideological or may be, as a collection of voters, at various ideological positions.

@gVOR10:

Unfortunately, it’s much easier to measure elected leaders’ behavior through their votes than the general public.

@Steven L. Taylor:

Yes, hence why I keep saying that people ought to focus on the swing states. The centrist swing voter in that handful of states is very important IMO, because they can tip the balance in a Presidential contest, unlike a centrist/swing voter in California or Alabama. And yet few seem interested in characterizing or discussing this group.

I think the reality is that the combo of social liberalism and fiscal conservatism (as uselessly vague as those terms are) just isn’t very popular generally, especially the fiscal conservatism part.

@Andy:

For the EC, yes. But I don’t think anyone is arguing otherwise. But that really isn’t the point of the post nor of the general concept under discussion.

Yes, well, I did use the descriptor “dream” and I am referring to a particular flavor of columnist.