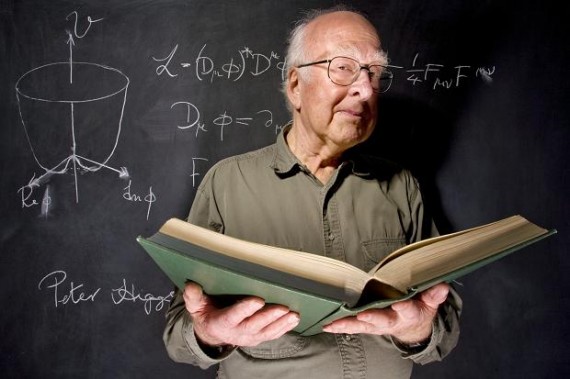

Peter Higgs Not Productive Enough for Today’s Academy?

Nobel physicist Peter Higgs says he could not make it in academia today.

Nobel physicist Peter Higgs says he could not make it in academia today.

Guardian (“Peter Higgs: I wouldn’t be productive enough for today’s academic system“)

Peter Higgs, the British physicist who gave his name to the Higgs boson, believes no university would employ him in today’s academic system because he would not be considered “productive” enough.

The emeritus professor at Edinburgh University, who says he has never sent an email, browsed the internet or even made a mobile phone call, published fewer than 10 papers after his groundbreaking work, which identified the mechanism by which subatomic material acquires mass, was published in 1964.

He doubts a similar breakthrough could be achieved in today’s academic culture, because of the expectations on academics to collaborate and keep churning out papers. He said: “It’s difficult to imagine how I would ever have enough peace and quiet in the present sort of climate to do what I did in 1964.”

Speaking to the Guardian en route to Stockholm to receive the 2013 Nobel prize for science, Higgs, 84, said he would almost certainly have been sacked had he not been nominated for the Nobel in 1980.

Edinburgh University’s authorities then took the view, he later learned, that he “might get a Nobel prize – and if he doesn’t we can always get rid of him”.

Higgs said he became “an embarrassment to the department when they did research assessment exercises”. A message would go around the department saying: “Please give a list of your recent publications.” Higgs said: “I would send back a statement: ‘None.’ ”

By the time he retired in 1996, he was uncomfortable with the new academic culture. “After I retired it was quite a long time before I went back to my department. I thought I was well out of it. It wasn’t my way of doing things any more. Today I wouldn’t get an academic job. It’s as simple as that. I don’t think I would be regarded as productive enough.”

There is an interesting argument, indeed, to be had over the merits of the academic publishing system that has evolved over the last couple generations. The proliferation of niche journals combined with pressure to publish even at the “teaching schools” mounting has rendered the value of most of what has published—and the trade-offs in terms of teaching students, especially at taxpayer-subsidized universities—debatable.

Higgs doesn’t do a great job here advancing that debate, however. He seems to be implying that he largely stopped producing once he had his Nobel Prize-winning breakthrough 49 years ago. Whether pressure from the department to do more than 10 papers in the course of half a decade of employment at a top-tier research university was warranted depends entirely on how important those papers were and how much value he added as a teacher. Was his brilliance enchanting undergraduates who would go on to be physics majors? Was he mentoring doctoral candidates who were themselves making outstanding contributions to the field?

Interesting post, Dr Joyner. I’d have missed it except for OTB. It corresponds to something I’ve noticed in my family (loaded with Doctors of this and that, MDs and RNs) and professionally. The present demands and climate are universally loathed. Physicians urge their kids to NOT go into medicine; academics say they’d not follow the same path today that they took back in the day; RNs lament that the personal touch has been replaced by huge volumes of what is essentially make-work clacking away at a computer.

I’ve kind of dismissed a lot of this over the past few years. At this point the family has continued to produce new RNs and MDs so obviously the younger folks anticipate a rewarding future in the old paths.

But I bet a heck of a lot of people read Dr Higgs remarks and silently think that they know just how he feels.

He might also be implying that it takes a lot of time to develop a really big insight, and such things often lead nowhere. He’d not be alone in that; Einstein spent decades working on his grand unified theory, which came to naught.

And its interesting that many of Einstein’s biggest discoveries (photo-electric effect, special relativity, explanation for Brownian motion – any one of which would have been Nobel Prize worthy in itself) came when he had the relative peace and quiet of working in a patent office with no publishing requirements.

I remember my graduate supervisors in physics complaining about the same thing – the pressure to publish and get grants means young researchers (still without a reputation) have to go after short, relatively safe projects instead of trying for the bold new research that in fact would ideally be done by young researchers whose ideas aren’t set.

It might be that his primary post-Nobel contribution to his institution was as a marketing tool, lending the cachet of his prize.

I’ve seen an awful lot of instances of scholars whose outputs (however measured) declined drastically after they received tenure. As Dr. Johnson is said to have remarked, the prospect of being hanged focuses the mind wonderfully.

IMO this is all just human nature. People respond to incentives.

I think you missed his point James. He is saying that without the freedom to wander aimlessly about the world of physics, he would not have been able to indulge his curiosity in the way he felt was most rewarding, and productive, for him. If he had had to publish 3 papers a year (I have no idea of what is expected in today’s academia, so that # is straight outta my a$$) he would not have been able to fully explore other slightly less than fruitful endeavors (meaning, not finding anything new, just confirming current theory).

It’s not just true of Universities but corporations as well. There used to be a lot of pure research that went on at places like Bell Labs. While most of it led no where that was also where the big breakthroughs came from. My first employer, Tektronix, was like that. Neither of them exist anymore and in this world of leveraged buyouts, quarterly profits and stock prices there is simply no place for it anymore.

@JohnMcC: Yes, I think that’s right. The work professional environment is generally more demanding and less rewarding than in the past.

@george: @OzarkHillbilly: Sure. The problem is that he framed it in terms of his post-seminal work. If he argued that he’d have been fired before coming up with the Higgs’ Boson idea because it took him so long to develop, it would be an outstanding point. But he’s saying that he’d have been canned post-Eureka! because he wasn’t producing much work in the ensuing decades. Was that work also making significant impact in his field? Or, as @Dave Schuler suggests, was he just coasting along once he made his breakthrough? I suspect it’s the former but really have no idea. But I have less sympathy for the latter.

And, yes, once he got nominated for the Nobel—way back in 1980—he became valuable as a marketing tool. But that’s a different thing.

It’s a hell of a luxury to have a career based on one idea.

I have to work every day.

Who chooses who gets to space out all day for years on end?

Wow, you just made Higgs point better than he did. The idea that “publishing” has some kind of value is bunk. Publishing garbage is still garbage (ok, fine, its peer reviewed garbage) and a huge amount of stuff published today is garbage. Very few of the papers will ever be cited in future papers and if your work is not cited, you have not contributed any thing to the advancement of knowledge.

The measure of your productivity as a scholar is not how many papers that you have published, especially now that there are so very many ways to get published. It is how many citations in other papers your work has. I think Higgs has that covered.

@C. Clavin: I have to work every day.

And what you do compares to “his groundbreaking work, which identified the mechanism by which subatomic material acquires mass”…how?

Mike

@jib10:

I do agree with this in part, but would dissent in part (and I say this after having just this week having sat through an all-day, university-wide T&P review meeting for a school that is predominantly oriented towards teaching).

On the one hand, as you say, having something published does not mean that the item published has a great deal of merit (although “garbage” may be unfair and unkind, at least if it has been adequately peer reviewed). On the other, even if a given paper is not making a major contribution to knowledge, it does mean that the author is actively engaging in their field in a way that will likely enhance and contribute to their teaching (and likely will, over time, contribute to more mature work output). If a person does little to nothing, however, this very likely means that they are not actively engaging their own fields of study, and this translates (negatively) into the classroom. Do we want professors who are teaching at the graduate level, for example, who have no discernible scholarly output?

The focus in these discussions is often on the fact that any given paper may only have a handful of readers, and this may be true, but such a focus ignores that those who are actively involved in their field should, by extension, be better teachers (as opposed to relying mostly on what they learned in graduate school) as well as the fact that a variety of smaller works can have a cumulative effect (e.g., I wrote and presented a number of conference papers over a space of years that I am pretty sure very few, if any, people read–but those papers were stepping stones to a book, which certainly has moderate reach, but was well-received in my little niche of the academic world).

While I can understand it, several people here obviously would not produce much of anything but for the spur and lash of the flat-out need to survive. The sort of mind that spends decades obsessing over a single problem and, sometimes, changing the way we think about the world, well these people do not follow up success by munching chips on the sofa in front of the tv until the boneyard beckons. No, they continue thinking; that’s what they do. Universities used to provide a refuge for these types, a place where people of talent provided people of genius with the time and conditions necessary for original thought. Mediocracy, it need hardly be said, likes to be seen to be busy and generally recognises nothing higher than itself.

This reminds me of a story, which I copy here straight from another site:

Henry Ford told of an efficiency expert who complained about a fellow down the hall, sitting with his feet on the desk. Ford replied, “That man once had an idea that saved me a million dollars. When he got it, his feet were right where they are now.”

Steven makes a good point. The increasing specialization of study in the academic world inherently means that any given work or even a body of work has a limited audience.

What complicates the story is that the work Higgs got the prized for was independently discovered by a number of people. And since the Nobel prize is only awarded to three people at a time not all the discovers get equal attribution.

From what people tell me Guralnik, Kibble, and Hagan actually made the discovery first but published later. Around the same time two young soviet physicists also discovered the Higgs mechanism but their contribution didn’t leak out of the Soviet Union until a few years later.

@JohnMcC:

Hasn’t it long been a theme that outwardly successful people surprise you by advising their kids not to do what they did?

I question it. I think it is too often “been there, done that” reflected on kids who would probably have a completely different experience anyway.

On the main theme though … I think our connected world cuts two ways. Many more millions are exposed to cutting edge research than 50 years ago, but our connected world does favor connected workers.

Somewhere there is a kid posting on reddit while he works a physics problem. 50 years from now that kid will have a Nobel. That’s our world.

(Hell, maybe the kid is playing Call Of Duty while his experiments run.)

@JohnMcC:

Excellent points, and they very much are in line with many conversations I’ve had with professionals in all fields. To a person, all of them say that they are working harder and enjoying their profession far less than they did even 20 years ago. It does seem to be connected with our workplace technology and the productivity expectations.

Thirty years ago independent physicians and surgeons were not corporations, now they are. My own doctor and her colleagues closed up their five physician group practice and signed on with large medical provider groups (Sutter, St Joseph, Kaiser, etc) because they were tired of running a business and wanted to be general practice doctors. Now I’m sure that the corporate demands of an integrated medical group like Kaiser puts pressure on them, but that is not the same kind of pressure that comes with being a physician and running a business at the same time.

More on the corporate research end here. When I first went to work for Tektronix 40 years ago they had a huge R&D department. Scientists and engineers were given free reign to chase their dreams. One of the projects I worked on was a projector to display images from a computer. We worked on it for well over a year. Our project was a failure but the science and engineering we developed is now found in every projector available today. I was also part of a project to develop a color printer. That was a success and that division was sold to Xerox several years ago and is still going strong. This R&D is for the most part no longer done in the US. Is Microsoft innovating? The answer is no – they are simply adding bells and whistles to existing platforms. Even Intel is only making improvements to existing technology rather than looking for the next technology.

The world needs “mad scientists” for innovation and they are no longer encouraged.

@Ron Beasley:

https://news.ycombinator.com/news

@MBunge:

Um…maybe…its been tentatively confirmed…and it’s called theoretical physics for a reason.

And how many Higgs never came up with a boson?

Let me come at this from a different direction. I write young adult books. I am, by any measure, absurdly productive. In fact I’d easily make the top ten for most prolific kid/YA authors, having written more than 150 books.

Harper Lee wrote one book, To Kill a Mockingbird. It’s not false modesty to say that she accomplished more with one than I have with 150. But apparently in an academic environment, I’d be the favored one, and she’d be let go.

I’m getting heartily sick of the tyranny of the STEM-minded, with their primitive faith in numbers as the alpha and the omega. Not everything can or should be reduced to numbers. Some of what you get out of people takes time to develop. Some of what the human race does best, it does in very limited quantities. More is not always better. Efficient is not always right. Faster doesn’t always get you from A to B more efficiently than slower. Life is not engineering. We are not tools.

@JohnMcC:

You see it in other professions too. It’s rare to find a lawyer or an architect, say, who encourage their children to follow in their footsteps. Personally I considered it a victory every time I dissuaded one of my assistants from going to law school.

I don’t think this was as true 30 to 50 years ago. Something…has gone wrong.

@Rafer Janders:

I’d love to see my kids do my job, if they wanted to. It’s one of the greatest jobs on earth. Short days, good money, almost 100% autonomy, wear what I want, work how and when I want. I’d recommend it to anyone.

@michael reynolds:

Its sounds great, but you’re also highly self-motivated, creative, and comfortable working alone for long periods of time. A lot of people need a different work environment, need to be around people, etc.

@Rafer Janders:

Thank you. But I’m those things in large part because I simply evaded capture by the system. HS drop-out, one semester of college.

Because we believe in all things numerical and eschew what we used to call “poetic data” we create a system that, whether it intends to or not, drives relentlessly toward the mean, toward mediocrity and conformity. It discourages outliers. It undermines the mad scientist and the creative outlier in order to make widgets of humans.

We make philosophical choices that we aren’t even aware of and of course don’t think through, and get results, some good, some bad. The fact that so many professionals don’t want their children doing their jobs is an indicator that something is wrong. I think what’s wrong is that we’ve placed the number on a pedestal and discounted the human.

That’s a choice. It’s not the only way society can be structured. “Measurable” is not the most important virtue. When it becomes the be-all and end-all you get a lot of unhappy people.

@michael reynolds:

Ha! Well Sir, one thing we STEMs do is logic. And logic dictates while a Post Hoc fallacy is bad, a “Pre Hoc” one is even worse!

You can’t blame modern engineering for things that came far, far, earlier in human history.

And yet systems of numbers literally defined civilization, arising on clay tablets of the Mesopotamians.

@this:

Or independently developed, the knot-languages of the Andes!

@michael reynolds:

It is not the stem minded it is the actuarial minded.

Both STEM-minded and actuarial-minded understand numbers, but that is largely where our companies part.

@michael reynolds:

Actually that’s not STEM minded. STEM minded is spending years just thinking before producing anything – Einstein, Newton, Lagrange, Gauss – the list of the greats in STEM who took that approach is much longer than those who produced a continuous flow of small results.

What you’re describing is admin and bean counting; universities and research institutes aren’t run by STEM majors or principles, they’re run by finance and commerce.

STEM isn’t about numbers, its about physical insights. Equations are just descriptions of those insights. Moreover, the equations aren’t about numbers either, they’re descriptions of patterns, which is a very different thing from numbers. Accounting and finance are about numbers (or so I’ve been told by people in those fields); very different than STEM.

@James Joyner:

That’s a fair point, his phrasing is unclear – I immediately assumed he meant the former, because that’s what I’ve seen among some very good physicists – they never stop thinking and working on problems, though they often tackle one beyond their (or anyone’s at the time) capabilities. If he meant he just sat around watching TV afterwards then yes, his argument isn’t very convincing.

@michael reynolds:

It is a rather important value when designing systems for millions of people.

Without measurable data of some sort how do you judge whether or not our schools or anything else are doing what is intended?

I think we test too much and too poorly, but we do have to test somehow.

@Rafer Janders:

It works out in the long run.

Kids told not to become academics become lawyers.

Kids told not to become lawyers become doctors.

Kids told not to become doctors become academics.

@Grewgills:

I read a little book once that tried to distinguish between natural measurments and forced ones. Height or weight or temperature are natural measurements. IQ or GDP or MBTI are not. They are somewhat forced, because a natural measurement is not available.

Perhaps even, when Michael groups some things as STEM he is doing something not really natural. I mean, how many movies (without spaceships or dwarves) would a STEM have to see each year to degrade his pure STEM status?

@john personna:

No, numbers did not define human civilization, they merely counted some of its elements. Before there were numbers there was curiosity, courage, the will to survive, greed, pride, external threats, the human body, and many other elements, and these form the basis of human civilization. Numbers were and are extremely useful tools, but they are tools in service to human need and human emotion.

And numbers standing alone are essentially useless without words. We have 12. . . what? 12 what? Oh, 12 oxen. Very different than 12 cows or 12 slaves or 12 bricks. 12=12=12, but 12 oxen does not equal 12 bricks.

First, the human and his environment, both external and internal. Then pictures. Then words. Then numbers.

There’s a hubris in the STEM-folk. Every 30 days what do we get? A headline that reads jobs/GDP/healthcare costs either fail to meet or exceed expectations. But the notion is always that we merely need to tweak the numbers, and not that what we are observing is a complex human-driven phenomenon that defies mathematical modeling.

We even try to use numbers to describe emotion. We compare “happiness” numbers from Sweden and Japan and the US, as though this meant anything at all, as if happiness is a measurable object, the same across all cultures.

That’s just one of myriad examples of what is a sort of religious faith in numbers. We are misled by the certainty of formula, the fact that 1 + 1 always equals two, into believing that numbers reveal some transcendent truth. Sometimes numbers do, other times they don’t, and sometimes the attempt to apply a number is pure nonsense and diminishes our understanding rather than increasing it.

Long time ago I read a sci-fi short story (I forget the author) that insisted only math would be needed to communicate with extraterrestrials, because math could describe everything. It’s the kind of thing that sounds cool and clever until you ask the numerical description of Hamlet, or a glance from a pretty girl, or the taste of an orange. Almost all of human life and human civilization defies reduction to numbers, and if one insists that numbers are all one needs, one misses most of life.

@Grewgills:

Aristotle taught Alexander. I doubt there was a standardized test involved. The test was Alexander’s life. Socrates taught Plato. More broadly, artists “teach” other artists, whether in person or just by example.

Most importantly, parents teach children. The vast majority of what you know you learned before you ever went to school. You learned the basic architecture of language, of spatial relationships, of permanence and impermanence, of gesture, expression, distance, a million things without which you’d never have made it to school.

And you learned all that without your progress being numerically described. We have to test only because we institutionalize and standardize. And the results? Have you seen another Bill Shakespeare walking around lately? Another Da Vinci or Van Gogh? The educational system, with all its lovely metrics, is virtually designed to eliminate Van Goghs.

And I would add, even in math. Have we had a second Newton or Leibniz produced by our well-measured educational system? No. Newton, run through an American High School, would have ended up engineering knobs for the dash of a Chevy Impala.

One final point, and then I’ll stop filibustering: you can’t measure what ain’t there. So if you’ve built a system that produces 1000 bright, capable mediocrities, you figure: success! Because you can’t measure the fact that in doing so you destroyed one Newton. To create a Newton you have to respect the random.

@michael reynolds:

That does not answer my question.

All of what you described are small group very personal interactions. Those are great and everyone needs them, but in a large complex society, at least on in which you want any social mobility you need a lot more than that. Public schooling, as much as you disdain it, has done more than just about anything else to enable the social mobility.

There are people writing today that are every bit as good, so yes. Shakespeare didn’t do it all on his own either, most of what he did was collaborative. If he were alive today, he’d likely be writing for TV and or movies and producing great work.

and

Bull shit. I get that the education system as you encountered it served you poorly, but that doesn’t mean what you seem to think it does. Open your eyes and look around you. There are more brilliant artists, authors, scientists and mathematicians than ever before and not in just raw numbers (there are a lot more of us after all), but more per capita. The biggest reason for that is free and ubiquitous public education. It is the best playing field leveler we have yet found and is the basis for most of our economic and social mobility.

Education can stand A LOT of improvement, but you’re tossing out the baby with the bath water.

@michael reynolds:

How many Newtons have we lost over history because he (or particularly she) never had any education? How many peasants’ children in Newton’s time could have been him, if only?

You are speaking from emotion, not logic here.

@michael reynolds:

As a curious aside, I’ve heard that Feynman said the American school system of his time (unmeasured, fairly slow paced, almost no homework etc) was perfect for developing exceptional scientists, because it gave them time to develop their interests and imaginations. A more rigorous, measured system keeps boys and girls far too busy (with what is mainly work for its own sake) to let them do anything but digest what’s fed them. I’ve certainly heard Japanese scientists say the extreme workload of their school system is good for developing competent scientists, but detrimental for developing good ones.

Like I said before, its not STEM folks who want the measured, numbers oriented education you’re criticizing – its a lousy system for science and engineering education, where creativity and imagination are vital (unless you want to just copy whats been done before). Its admin and accountants who are behind it – and I suspect they’re behind it because politicians demand it, and I suspect the only reason politicians care is because voters have decided that this approach is going to be beneficial for obscure reasons.

@michael reynolds:

That is quite an elitist argument.

@john personna:

Exactly. I don’t think there are many of these pure STEM folk out there. Every scientist and engineer I have ever met has a wide range of non STEM interests. People don’t go into science or engineering or math because of a lack of curiosity or imagination.

@Grewgills:

.

I don’t believe you can support that argument with data.

We choose to standardize. It doesn’t have to be that way. We chose this educational system to prepare children for the marketplace. That’s not the only way to go about the job of education. It’s a choice, driven by our choice to value production within a capitalist system. It’s not chiseled in stone, it’s what we’ve done in order to make children into tools to be used by business in order to generate profit.

Now, you may argue that’s the best approach. Maybe it is. But it’s by no means the only way to educate. We have an entire country now being driven relentlessly through an educational system that prepares them to take tests to assess their progress through an educational system designed to teach them to take tests to assess their progress through an educational system designed. . .

And people think: well, I guess we’d better pile on some more tests. And down the rabbit hole we go, measuring our ability to measure our ability to measure our. . . what?

This may have been forgivable 20 years ago, even, but it’s absurd now. Humans are individuals. We have the means now to recognize that different people learn in different ways and at different speeds. This lockstep, one-size-fits-all system is obsolete. It’s obsolete in terms of its goals as well as its methods. It’s doing just what we don’t want it to do: pounding down the nails that stick up.

Education has to be a lifelong process. Don’t believe me, ask any of a million unemployed people with the “wrong” skills. Education does not have to be organized by chronological age – age is an imprecise tool. Education doesn’t have to be a single continuum running from kindergarten through your BA or BS. It can start and stop and start again. Education does not require a special location in all cases, though in some it may. It doesn’t have to take place between 7 AM and 3 PM.

We do all of that because it’s easy and it fits existing patterns. We do it because test scores drive real estate values. We do it because that’s how educators were taught themselves. We do it because special interests, from educators to politicians to various employers, profit from keeping things the way they are.

By the way, I’m not trashing STEM folk. I’m typing on a lovely Mac Air developed by STEM folk (and made sexy by Jony Ive.) I love science. I have a kid who is STEM folk.

My objection is to the hubristic and demonstrably false notion that science, technology, engineering and math represent the only values we need to maintain a civilization. And I’m objecting to the reflexive reach for the next number that will somehow reduce everything to a formula. It’s the philosophy I object to, this notion (unspoken usually, but quite real) that humans are a math problem, that we could all be happy if only we could figure out the algorithm.

Humans are not numbers. Until you eliminate humans, numbers will be of limited utility in describing, or prescribing for, the human race. Other systems of thought exist, and other priorities, and we should be more humble and more open-minded in considering the importance of things which don’t lend themselves well to plus and minus signs.

I feel pretty good about my observation that writing systems, numbers, and civilizations were founded together. Numbers were used for accounting, tax, and bureaucracy long before they were used for STEM. Heck, numbers were old when alchemy was new.

And so of course the argument that STEMs invented numbers and crushed the human soul … “needs work.”

Very related:

http://mobile.bloomberg.com/news/2013-12-05/lazy-journalists-aren-t-to-blame-for-death-of-print.html

@michael reynolds:

I am positive that you cannot prove otherwise.

More people and a much wider swath of the populace now has access to information to self educate than ever before. That is doubly true when you consider how recently women have been allowed that access.

Do you really think that Newton had a typical upbringing for his time? Do you think that most people then had the time or other resources he had to pursue the goals he did? Do you really think that the King’s School of 1655 and Trinity College of a few years later were closer to the individually tailored schools you envision than to schools as they are today?

Newton had plenty of forces trying to beat down his head, but he was too damn stubborn to let them. He would be a brilliant scientist or a brilliant something if he was born today and with the communications network made available by all those STEM folk he would be able to share whatever he produced.

Who thinks that? Certainly no scientist or engineer that I know. All of the scientists and engineers I have known (including some that helped design that fancy notebook you’re using) support arts and physical education in schools. The ones with children foster curiosity and creativity in their children. Those children and yours and the children of all parents that are creative and curious and have the leisure to pursue those interests are lucky. All of those children will be fine. Their little heads won’t be pounded down, because they have the resources at home to make sure of that.

As I and others have pointed out, it is not STEM folk that are pushing the over testing or the teaching to tests we see now. It is accountants, professional administrators (that often have little or no experience actually teaching), lawyers, and politicians. Last I checked almost none of them are STEM associated. Those people of late have decided to focus more on STEM because their little actuarial tables tell them that is where the money is. In short you are raging at the wrong target.

BTW science, technology and engineering are necessary for the giant civilizations we have today and we would not have civilization on anywhere near the scale we do now were it not for those STEM folk. Then again we wouldn’t have the global climate changed or as much of the habitat and species lost caused by the technology and the increased population it allowed.

@michael reynolds:

To speak to some of your examples more directly:

Shakespeare (and Marlowe who was arguably as good) and Newton went to British public schools in the late 16th early 17th century. If you think modern American schools do more to smash down the heads of those that stick out than British public schools then, I have a bridge to sell you.

VanGogh went to a Catholic village school with one teacher to 200 students. Again, if you think that environment did less to crush individuality I have another bridge to sell you.

@Grewgills:

B-I-N-G-O. Though I’d also add economists and sociologists (though not all) to that mix.

I would suggest the excellent collection of essays on this topic entitled “Audit Culture”:

http://www.amazon.com/Audit-Cultures-Anthropological-Accountability-Anthropologists/dp/0415233275

This type of self and institutional disciplining and auditing in a fascinating byproduct of the enlightenment and the advent of mass manufacturing.

It’s not coincidence that alongside the rise of these systems, we’ve also seen the development of PhD programs in things like “Higher Ed Management” (because a University can’t have a non PhD running major sections). This ironically get’s to Steven’s earlier point about the hyper-specialization of modern academics.

@Grewgills:

Correct me if I’m wrong, but “Public Schools” mean something entirely different in the UK (even of that day). I mean Oxbridge are considered “public schools.”

I really think that McArdle’s invocation of Baumol’s cost disease cuts across the original complaint and Michael’s variation in an interesting way.

Writers and thinkers could be asked to live simple and unconnected lives … but they actually demand the rewards of that connected life.

Why do we have to measure if our education system is “working?” I don’t find it inconceivable that we could provide education and leave it at that. Why the big hubub over forcing a horse to drink? The ones interested would run with it and leverage it into other productive things and the ones not interested wouldn’t.

Lets just cut to the chase…we have a economic system that has a limited number of elite, middling, and lower class jobs. Grades in schools are the part of the discrimination process whereby the younger generation qualifies for where they’ll end up in the scrum. Of course, grades aren’t the only discriminator–personal connections to elite persons or institutions plays an even larger role so the C-student at Harvard (yes I know…a unicorn) is going to have access to more high-level opportunities than the A-student at State U. Nobody really cares if a kid learns or not on the macro level. Grades are part of the rack and stack process.

In sports there is a concept called SASS– Specific Adaptation to Specific Stress. In short, it says that residual benefits you get from performing activities similar to game activity is limited. In other words, you don’t get to be a more powerful tackler in football by doing olympic-style weight lifting. You become a better, harder tackler BY TACKLING PEOPLE… ALOT. Now that doesn’t discount weightlifting and working on technique but it does help guide into how the trainee prioritizes training time.

Likewise, school and testing isn’t going to help kids do what we actually want them to do. We want them to be intuitive, imaginative, and have the ability to go into an unfamiliar situation and solve problems by identifying relevant factors/ignoring irrelevant ones and formulating a plan of action. Schooling provides only a small portion of these skills. The rest kids would have to learn by actually doing those types of exercises. It’s an ability that must be dialed in with live fire….this would be the opposite of testing as its non-standard and subjective–like life. Just like SASS says that the kid lifting weights to become a better football player actually is only becoming a better weightlifter–what we have now is kids that are getting better at taking tests. A skill no one in the real world gives a damn about.

@OzarkHillbilly: I don’t publish (at my, untenured, rank, I can meet my service to the institution requirements by doing workshops for other departments and student service organizations), but among those in my school who do, the conventional wisdom is that it takes approximately 18 months to get a journal article published and that one needs to be working on 3 research projects (or three directions for one project) in order to publish once a year.

Of course, the most nefarious thing happening at my school is that some tenured people “hitch their wagons” to someone else’s star by “offering” the prospect that since journals don’t usually publish the work of graduate students, those students need the “assistance” of their mentors–usually in the form of the position of lead author–to get published and start their careers.

Things haven’t changed much, in the days of my youth, one graduate seminar on “research writing” came with the notation in the course description that “all student submissions will become the property of the class instructor” (interestingly enough, a violation of the laws of the state in which I lived, but ignored by both the administration and the campus office of the Attorney General’s representative).

@mattbernius:

Yes, it means something rather different, but to pretend that British public schools of that day were more individualized and less likely to bat down the heads of the kids that were different is just silly.

@george: I think what Feynman said is for the most part true. The American school system encourages mediocre results. I attended high school from 1960 to 1964. I did extremely well in all the placement tests but my grades were horrible, I was placed in an under achievers group and the advisor asked me what my problem was. I answered that school was interfering with my education. I got into college based on achievement tests and did much better but still not great. In spite of that I had a very creative and successful career as a scientist and engineer.

@Ron Beasley: I might add I think that is because I always refused to think inside the box. If someone told me something couldn’t be done I set out to prove them wrong. Yes, I was often wrong but when I wasn’t it was really special.

@michael reynolds:

Writing is a log-normally distributed career field where a few people make a lot and most make little. I have always thought that most school counselors, advisers, and even parents are not capable of understanding log-normal career fields versus normally-distributed career fields.

I seem to remember the same complaint that Professor Higgs made about the present educational system was also stated by one of the most brilliant economists out there–he had only written three papers, each of which were seminal. Forget who it was.

And please remember that the success rate in theoretical physics is damned low. I remember as a grad student bitching to my boyfriend (also in theoretical physics) about running down blind alleys all the time and he gave me a hard look and said:” ninety percent of the time it’s not going to work out. Get used to the ratio or get out of theoretical physics.”

It would be much easier to fill one’s publication quota if we could publish all our failures as well….luckily, you can at least get a doctoral thesis out of it.

@grumpy realist:

And really, is the Super Soaker such a lesser accomplishment?

I think we have way more research universities then we need and should be developing more teaching oriented 4 year institutions, kind of like 4-year community collages. The level of teaching in most research university classrooms is scandalous. I work at a university, I hire students from the IT school all the time who are taught nothing practical about computers.

While I understand that they are not training these kids for desk-side support there are things like deployment engineering and computer management that make up a huge part of current life-cycle management and those topics are being abandon in favor of learning about current throughput of copper vs fiber, which while interesting, is the kind of knowledge that is mostly useless in the real world.

@Rick DeMent: Many people have made the same sort of complaints about law school education….I think the most useful course I’ve had is the International Business Transactions course. I now know exactly what a Bill of Lading is, and no one is ever going to frighten me with one again!

@Rick DeMent:

I’d argue the things you’re looking for should be taught in a community college. I’ve hired a lot of engineers over the years (not surprising since I’m an engineer) – I expect them to have the theoretical background to quickly pick up whatever practical skills we are using at any given time (and which change fairly quickly, as technology advances).

The last thing I’d want is to hire someone with a set of current practical skills that isn’t backed with the theoretical understanding to quickly pick up new practical skills when necessary. We’ve tried that approach – hiring engineering technologists instead of engineers, and in the long term its generally not nearly as useful as hiring engineering degree graduates. In fact, many (and probably most) engineering companies have tried that approach, and give up on it for the same reason – technology changes too quickly to hire someone based on current practical skills. The ability to pick up new skills is vital, and experience shows that engineering college graduates (for engineering problems) are much better at that than technologists who come out with better practical skills but huge holes in their theoretical background.

Its the difference between hiring someone who knows all the phrases in a language guide, and someone fluent in the language. The person with the phrases might be more useful at the start, but after a few months the fluent person will be far more useful.

@Steven L. Taylor:

But my problem is defining a published paper as “discernible scholarly output”. I think that is wrong. You can publish garbage, it has been shown that peer review does not guarantee quality. In fact, it seems in many cases to enforce group think. Every one gets a pretty good idea of what they can say and more importantly HOW they can say it.

I keep thinking of David Graeber’s essay On Bullshit Jobs and the cult of publishing in academy seems to me to be a classic example. A bullshit job is one that no one will notice if you dont do it. A paper that is not CITED (and I am talking about citations, not reads) is a paper that no one would have noticed if it had not been published.

Now many papers are not cited for years, if not decades and then when academic fashions change, find themselves in vogue. So it is hard to say when

Maybe it is a good theoretical exercise for a teacher to go through but really, that does sound like rationalization. There are better ways to spend your time if you are looking at how to improve as a teacher.

Now it is true that many papers are not cited for years, if not decades and then when academic fashions change, find themselves in vogue. So it can be hard to judge who is productive on cites alone. But I find the idea that some one can make a fundamental contribution to the field like Higgs did and then be dinged for not doing enough industry acceptable busy work there after, well, bizarre. The purpose is to move knowledge forward. One great discovery is worth 1000 small insights.

@jib10: But to get cited, and to make a contribution requires publication. If you publish nothing, and there is no requirement that you do so you do worse than produce no citation papers, you produce NOTHING.

For your position to make sense you have to explain to me how producing nothing (and therefore not having to put any effort into scholarship at all) is a preferable outcome.

@jib10:

I would be happy to hear your insights.

Speaking for myself, work on conference papers and publications has been a big help to me in the classroom.

@george:

I don’t disagree with this but the point I was trying to make is that we need more 4 year institutions where the emphasis is on instruction, not research. Instruction at every 4 year institution I have ever been to is wildly inconsistent at best. Even then the best instructors are typically those who are adjuncts unburdened with the pressure to publish. Community Collage instructors, in my experience, are far superior as instructors of course material. It is almost impossible to sanction an instructor on the basis of bad teaching alone at even a class 2 research University.

@Rick DeMent:

I don’t disagree with that, so long as those four year institutions are still teaching the necessary theory instead of teaching “practical” skills. The problem with Community Colleges is that, whether their instructors are superor or not, because they aim at transmitting practical skills instead of the theoretical basis for a lifetime of changing skills, the resulting students are generally far less well prepared than from universities for an engineering world where necessary skillsets change frequently and often dramatically.

I don’t know if that’s because the instructors at the Community Colleges don’t have the background to teach the theory (I wouldn’t expect this to be the case – I assume for instance a physics teacher at such a college still has a Phd in physics and so is comfortable with basics such as the Lagrangian and Hamiltonian, Maxwell’s equations, the Dirac equation and so on), or because the Colleges see no reason to teach such things (ie their goal is more short term practical), but the results are pretty clear – the students graduating from them just don’t have the theoretical background for most engineering work.

@john personna:

While I largely side with you in this disagreement with Michael (like, 90% side with you), I think you’re missing something with your numbers made civilization argument. Numbers from early civilizations are amongst the first historical records we have. That does not mean they were foundational – it means that’s the oldest stuff that survived for us to see/read/interpret. There were civilizations that pre-date the civs we know of that had written records that survived. Maybe they had writing/numbers, maybe they didn’t. But we don’t really know, because so much is lost.

Measuring things is obviously really important, and I think that any civilization would eventually need to be able to measure and record things. You certainly can’t tax without it. If that’s what you mean – that civilization requires numbers, especially as it grows and advances – well, sure. Whatever the problems with Michael’s argument, I don’t think he’s disputing that.

@Rick DeMent: @george:

The overwhelming number of American four-year institutions are teaching oriented. If it’s not a PhD-granting school, it mostly exists to teach. Increasingly, teachers there are expected to do *some* research. But they’re still teaching three or four classes a semester.

Community colleges are either teaching purely vo-tech classes or they’re teaching the most rudimentary introductory courses (freshman and sophomore level). If they’re teaching physics at all, they’re teaching one survey course. The instructors typically have a masters degree in the field although, increasingly, they have a doctorate because of excess supply.

@michael reynolds:

I think the “publish or perish” phenomenon is also equally present in the academic humanities as with STEM fields, but I could be wrong.