Putting the Amendment Process in Perspective

Continuing a discuss from below.

In James Joyner’s post below, Doug Mataconis raised the following points about amending the constitution:

The drafters of the Constitution recognized their own lack of perfection, and their inability to foretell the future, by putting the Amendment procedures of Article V in place. Yes, it’s a difficult thing to do, but that’s because it should be difficult to alter the fundamental law of the land without an adequate consensus. It’s not impossible, though, as has been proven on 27 different occasions in the past. The fact that we can’t, or won’t, come to a consensus on some issues isn’ their fault, it’s our own.

Emphases in the original.

I agree with the general sentiment, insofar as yes, consensus is a requirement for constitutional change and it shouldn’t be easy. But, I am going to blame the Framers in the sense that they choose an especially cumbersome mechanism that ultimately makes change very, very difficult and verges on the impossible when considered in conjunction with factors like the population-disparities between states and the general pro-conservative (small “c”) bias of the system (in simple terms, the system has a pro-rural bias, which tends to be opposed to change).

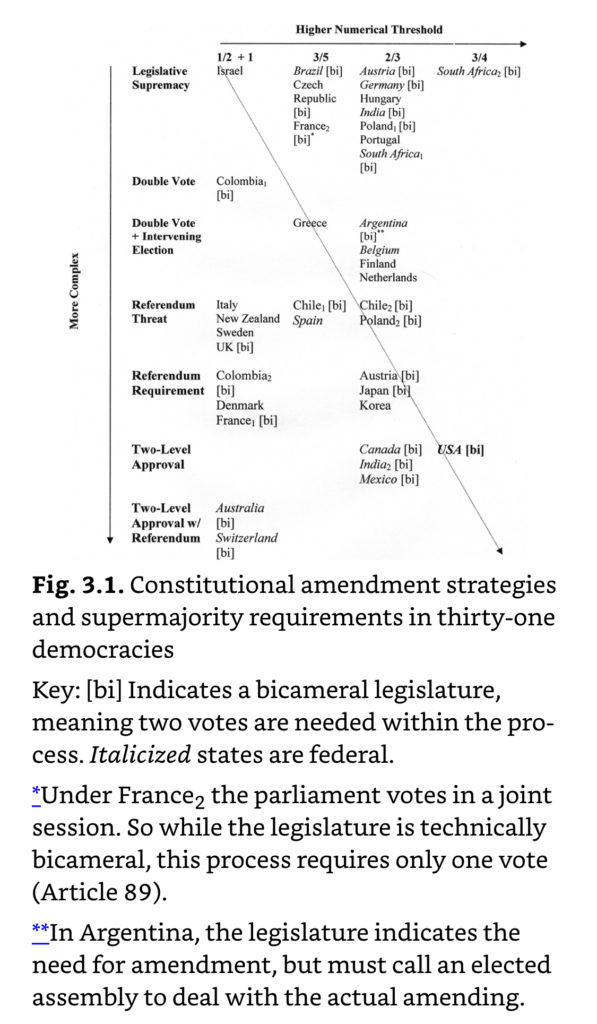

In our book comparing the US to 30 other democracies, my co-authors and I noted the amendment processes of all the constitutional orders under examination and found the US’ to be the most restrictive. It requires bicameral approval, two-level action (federal and state), and high thresholds (2/3rds at proposal and 3/4th at ratification). Note that these were not derived as the result of some theoretical scheme, but rather as part of the politicking of the convention.

Here is the figure comparing amendment processes. Top left is the most permissive, bottom right is the least.

Of course, Doug is correct that having a complex system does not mean that amendment is impossible. Of course what it does mean (and has meant) is that we have allowed constitutional change via Supreme Court because is has been the only viable route (whether originalists like it or not). It also means that systemic changes are likely only to come via major crisis/breakdown of the system,

On those last points, I do blame the Framers for creating such a restrictive process that reform is mostly coming in via different routes (the courts, and norm changes) and that major reform can only occur via crisis.

But, yes, contemporary Americans are to be blamed for not addressing major problems in the here and now.

But let’s talk about those 27 amendments that appear to prove that the system can be changed, but thinking them through actually show how little change the amendment process produces.

Consider: the first 10 are the Bill of Rights–basically extensions of the writing of the Constitution itself, all ratified by 1791.

The next two, the 11th (about who can sue states) and the 12th (fixing a flaw in the Electoral College), were early tweaks ratified in 1795 and 1804, respectively.

The 27th was actually one of twelve proposals written to be the Bill of Rights, so while it was ratified in 1992,* it belongs in this early set of immediate post-convention tweaks.

So, 13 of the 27 (48.15%) of all the amendments (almost half!) are from this very early period and are all of a piece with either fulfilling political deals linked to ratification (i.e., the Bill of Rights) or are linked to post-drafting tweaks. These are all better understood as part of the writing of the Constitution, as opposed to examples of how the process allows for change.

The next three amendments, the 13th, 14th, and 15th are the Civil War amendments, which abolished slavery, made former slaves citizens and extended equal protection of the law, and gave black males the right to vote (respectively).

Here we see how crisis leads to change–it took a bloody Civil War to rectify the sin of slavery (and only force of arms followed by Reconstruction led to southern states acquiescing to these changes–normal politics was not going to accomplish that feat).

So, that leaves only 11 amendments after the Civil War (if we count the 27th as I did above). If we note that two of those are about prohibition (its creation and its repeal, the 18th and the 21st) we are down to 9. This is not a robust process for addressing change.

And, I would note, that the last time we successfully went through the amendment process was 1971–almost a half century ago (longer even than the ~40-year gap between the 15th and the 16th).

All of this is to say that we need to consider all of this when evaluating exactly what our amendment process can actually accomplish.

*If you don’t know the story of the 27th Amendment, I recommend the following: How a C-grade college term paper led to a constitutional amendment.

All good points, Steven. I think you could also tie this in with what you have repeatedly hammered home, namely that the Founders did not foresee political parties. Perhaps the mathematics and realities made sense (more or less) as originally envisaged. But certainly not in today’s 50/50 world, especially where a significant minority hits well above its weight due to precisely the reasons that constitutional change would address.

Any democracy must suffer during a prolonged 50/50 period of disagreement, all the more so when the disagreement is acrimonious and zero-sum. And I’m not sure that any system can recover once a minority gains sufficient power.

We agree on all the substantive points here and I’ll defer on your expertise on comparative institutions. I’ll defend the Framers on the narrow grounds of the politics of the possible.

I don’t know the history behind the systems to which you’re comparing ours. But ours is incredibly old and were produced under rather unusual circumstances: 13 sovereign states loosely bound in a confederation coming together to produce something more efficient but not TOO efficient. It strikes me that, under those conditions, they moved a long way in 1) creating a House of Representatives that a moved them away from sovereign equality, 2) creating an Electoral College system of electing the President that also empowered high-population states vis-a-vis the extant system, and 3) was much more amendable than the extant system. I can’t imagine they could have moved much further and still gotten it ratified.

I wouldn’t pass over this one so quickly. Banning alcohol – a staple of human existence since our species first settled and began farming, was no small feat. The temperance movement provides a model that worked quite well and could very well work again. It took a lot of effort by a lot of people as well as a coherent strategy and leadership. The Civil Rights Movement was similar in how it effected change and I think cemented MLK Jr. as one of the greatest strategists of the 20th century.

So we know what works. The problem today is that no one is adopting these models and implementing an actual strategy that might be successful. Political action today consists primarily of sending money to DC-based lobby groups and complaining on the internet. It should be obvious that is insufficient to build the support necessary to make fundamental changes to the core elements of our political system. It’s usually insufficient for basic legislation.

In my view, the path forward and methods to build political support for changing the constitution is pretty clear – the problem is the people today are not invested enough in the effort to do much more than spend a bit of money and post on social media. We also lack leaders like MLK Jr. who actually have strategic vision and the ability to implement that vision.

@James Joyner: I certainly concur about the politics of the time and why what was produced was produced.

That said, path dependency can be a real bitch.

@Andy:

Sure, but it belongs in its own category for a couple of reasons.

First, one cancels out the other.

Second, and more importantly, it was a specific policy issue of the type that really ought to have been legislated. It was neither an extension of the definition of a right nor a reform to institutional practice. Those amendments are outliers and tell us very little about solving large structural problems.

You know, if amendments were easier to pass early on, and if it was clear to all that political parties were already dominant, the early governments really erred in not amending the Constitution in order to account for parties.

@Steven L. Taylor:

This needs to be on a shirt or something.

Because very yes!

I am a pessimist on the subject, and believe that the only changes we’ll ever see in the Constitution’s text going forward will arrive via convention, and will reflect the fact that at least 38 of the states have agreed on a partition of the country…

@Steven L. Taylor:

I wasn’t talking about the details of the policy, but the movement itself and the actions and strategy that got the amendment passed.

@Andy: I think the nature of those amendments is central to how they should be understood.

Sure, as a general issue they show that broad consensus can lead to change.

@Steven L. Taylor:

Yes, a broad consensus can lead to change – that much is obvious. My point, however, is about the methods and strategies used to build and achieve that since consensus doesn’t apparate from the void.

There are historically successful examples that could be adapted for today and the temperance movement is but one such example. In other words, it’s not enough to have a goal or a desire, a plan, strategy, and work is just as important if not more so.

I was startled to learn that the moral superiority of rural voters was an explicit thesis during the debates over the Constitution, and was not only taken as an axiom by the anti-Federalists but not really argued against by the Federalists. Along with the misguided expectation that local government would always be less corrupt than remote government, I think it’s one of the two most important blunders the Founders made.

@DrDaveT:

Yes, but the Framers can hardly be blamed for not forecasting the impact of mass communications. FDR was the first modern President because he fully utilized the power of radio and JFK took it a step further with television. We have, for more than my lifetime, reversed the natural presumption of the founding generation. Most of us not only know the names of the President’s family members but even his pets. Relatively few know their Congressman, much less their state and local representatives’ names, much less that of their family.

@James Joyner:

I’m intrigued that you think mass communications are the reason federal government is less corrupt than local government. Can you unpack that a little?

My experience has been that local government is corrupt because it is local — the powerful can exert influence locally, and the unpowerful cannot resist because they can’t get away from the consequences. The only effective counterbalance is a larger, more distant power whose actions are public.