Quiet Heroism

On the eve of Veterans’ Day, a new study sheds light on the nature of heroism.

An infantryman charges a pillbox in the face of enemy fire. A firefighter rushes up the stairwell of a burning skyscraper as office workers flee. A teacher shields her student from a schoolyard gunman with her body. Heroes all. But what personal qualities made them heroic?

In the movies, heroes are charismatic rebels played by the likes of Will Smith or Bruce Willis. But researchers who surveyed decorated World War II veterans found not all heroes are cut from the same swashbuckling cloth. Quiet types with a sense of loyalty and selflessness often have the right stuff, too.

“We often think of the gung-ho, John Wayne ‘Sands of Iwo Jima’ kind of hero driven to combat,” said researcher Brian Wansink of Cornell University. “But there’s a whole lot of these heroes that are much more along the lines of that Captain Miller character Tom Hanks played in ‘Saving Private Ryan’ — the reluctant high school English teacher.”

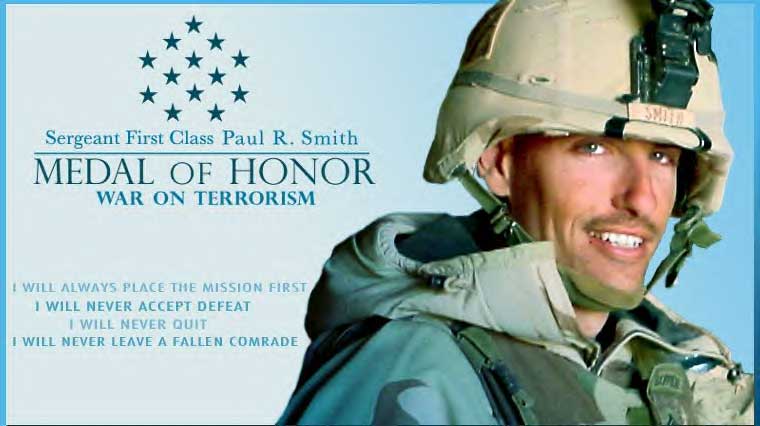

In a paper to be published in the management-oriented journal The Leadership Quarterly, researchers asked 526 World War II veterans who experienced “heavy and frequent combat” to evaluate themselves on qualities such as leadership, loyalty, spontaneity and selflessness. There were 83 men in the group who received a medal for meritorious service or valor — either a Bronze Star, Silver Star, Distinguished Service Cross or Medal of Honor.

Unsurprisingly, veterans who had been awarded medals tended to rate themselves higher for qualities like leadership, adventurousness and adaptability. Results became more intriguing when researchers divided medal earners into two groups: those who enlisted (“eager heroes”) and those who were drafted (“reluctant heroes”). The reluctant heroes scored higher than any other group in selflessness and working well with others.

The study suggests that quiet heroes rely on a deep sense of duty and esprit de corps as opposed to derring-do. That sentiment was echoed by several of the medal-earning veterans interviewed separately for this story. To a man, they downplayed any notion of heroism. “You show me a man who says he was brave over there and I’ll show you a liar,” said draftee and Bronze Star recipient William O. Carpenter, 84, of Champaign Ill. “Every one of us was afraid. Even the Germans were afraid.”

Former paratrooper Charles Murz was shot at more times than he can recall after dropping behind enemy lines in Europe and earning two Bronze Stars. Now 83 and living in East China, Mich., he scoffs at the idea he showed any particular courage. “Brave? Well, I don’t know about that,” Murz said. “I did what I had to do at the time that I did it.”

Of course, that’s the very definition of heroism. As George Patton famously put it, “All men are afraid in battle. The coward is the one who lets his fear overcome his sense of duty. Duty is the essence of manhood.” He also said, “If we take the generally accepted definition of bravery as a quality which knows no fear, I have never seen a brave man. All men are frightened. The more intelligent they are, the more they are frightened.”

Wansink said that understanding the range of heroic qualities can be useful to people who recruit and train soldiers, firefighters and police. A quietly respectful student might be able to distinguish herself as much as the extroverted high school quarterback.

Wansink also said the study underscores the effectiveness of team building in hazardous jobs, be it partnering police officers, having firefighters live together or organizing troops into units. “A hand grenade falls on the floor and leads you to do something other than if you didn’t know who these guys were and didn’t have a commitment to them,” he said.

That sort of loyalty effect has been noted before, famously by the late author Stephen E. Ambrose, who even named one of his books about World War II combat troops “Band of Brothers.” Writing in “Citizen Soldiers” of the men who liberated Europe, he noted: “What held them together was not country and flag, but unit cohesion.” “I did it because it was expected of me,” said 88-year-old Marcel Leschot, of Indianapolis, Ill, a Bronze Star recipient. “You never thought of your own preservation.”

Indeed, the idea that men fight for their comrades-in-arms more so than for lofty ideals of patriotism, belief in the cause, and the like has been long established. Indeed, it has been the essence of professional military training for decades.

Makes sense. “Heroism” in battle often means getting killed, or running a very, very high chance of getting killed, in order to save others. People who are driven by their own egos are less likely to sacrifice themselves, unless they’ve internalized their duty so much that they’d be ashamed *not* to risk their lives.

I’d bet that if you asked Marines, especially those who served in WWII, who were the bravest men they knew, to a man they would say Navy Corpsmen. And I’d bet that soldiers would cite Army medics.