Republicans Looking for an Enemy?

Matt Yglesias cites Francis Fukuyama, formerly of the neocon bandwagon, as evidence of a dastardly Republican plot to pretend that the United States has enemies:

During a BloggingHeads.tv appearance with Robert Wright, Fukuyama says of Bill Kristol and his circle at The Weekly Standard that during the 1990s “There was actually a deliberate search for an enemy because they felt that the Republican Party didn’t do as well” when foreign policy wasn’t on the issue agenda. The obvious candidates were either China or something relating to Islamic fundamentalism and, as Fukuyama notes, what they came up with was China. Then 9/11 changed things around, at least for a few years. I think this is very telling, and reveals a great deal about the mentality that’s been guiding America’s foreign policy during the Bush years.

Kevin Drum agrees and “just want[s] to hear Bill Kristol deny it.”

[Update: Upon re-reading of the quotation, it occurs to me that Fukuyama’s charge is directed at the Weekly Standard whereas Yglesias’ is aimed at Bush and the GOP. My response is directed to the latter, having an insufficient familiarity with or interest in complete works of the Standard.]

Let’s stipulate that Republicans tend to do better with voters when national security is an issue and that GOP strategists are aware of and exploit this fact. There are nonetheless a couple of problems with Fukuyama’s arguments and/or Yglesias’ interpretation of it.

For one thing, the Islamists had already declared war on us, twice, before George W. Bush even announced that he was running for president. That they are enemies of the United States would therefore seem to have been beyond dispute in 2000, let alone after the 9/11 attacks. Should Bush have ignored them for fear of gaining political advantage from this fact?

Not to mention the fact that, even after 9/11, the declaration of an Axis of Evil (including one non-Muslim state), and launching military action, President Bush repeated the phrase “religion of peace” so many times that it became, quite literally, a joke. And failed to call the enemy “Islamists” rather than simply “terrorists” until recent months?

Further, foreign policy was scarcely an issue in the 2000 campaign. I can scarely recall Bush mentioning China policy at all, with the exception of some oblique references to China as a “strategic competitor.” Indeed, a quick search of the 2000 presidential debates reveals no mention except for noting that it made no sense for the Kyoto agreement to exclude countries the size of China and India.

Indeed, the emphasis was very much on democracy promotion. An article by Condoleezza Rice in the January/February 2000 Foreign Affairs, “Campaign 2000: Promoting the National Interest,” was typical of the emphasis.

The process of outlining a new foreign policy must begin by recognizing that the United States is in a remarkable position. Powerful secular trends are moving the world toward economic openness and — more unevenly — democracy and individual liberty. Some states have one foot on the train and the other off. Some states still hope to find a way to decouple democracy and economic progress. Some hold on to old hatreds as diversions from the modernizing task at hand. But the United States and its allies are on the right side of history.

In such an environment, American policies must help further these favorable trends by maintaining a disciplined and consistent foreign policy that separates the important from the trivial. The Clinton administration has assiduously avoided implementing such an agenda. Instead, every issue has been taken on its own terms — crisis by crisis, day by day. It takes courage to set priorities because doing so is an admission that American foreign policy cannot be all things to all people — or rather, to all interest groups. The Clinton administration’s approach has its advantages: If priorities and intent are not clear, they cannot be criticized. But there is a high price to pay for this approach. In a democracy as pluralistic as ours, the absence of an articulated “national interest” either produces a fertile ground for those wishing to withdraw from the world or creates a vacuum to be filled by parochial groups and transitory pressures.

The first substantive discussion of China is more than halfway through the article:

For America and our allies, the most daunting task is to find the right balance in our policy toward Russia and China. Both are equally important to the future of international peace, but the challenges they pose are very different. China is a rising power; in economic terms, that should be good news, because in order to maintain its economic dynamism, China must be more integrated into the international economy. This will require increased openness and transparency and the growth of private industry. The political struggle in Beijing is over how to maintain the Communist Party’s monopoly on power. Some see economic reform, growth, and a better life for the Chinese people as the key. Others see the inherent contradiction in loosening economic control and maintaining the party’s political dominance. As China’s economic problems multiply due to slowing growth rates, failing banks, inert state enterprises, and rising unemployment, this struggle will intensify.

It is in America’s interest to strengthen the hands of those who seek economic integration because this will probably lead to sustained and organized pressures for political liberalization. There are no guarantees, but in scores of cases from Chile to Spain to Taiwan, the link between democracy and economic liberalization has proven powerful over the long run. Trade and economic interaction are, in fact, good — not only for America’s economic growth but for its political aims as well. Human rights concerns should not move to the sidelines in the meantime. Rather, the American president should press the Chinese leadership for change. But it is wise to remember that our influence through moral arguments and commitment is still limited in the face of Beijing’s pervasive political control. The big trends toward the spread of information, the access of young Chinese to American values through educational exchanges and training, and the growth of an entrepreneurial class that does not owe its livelihood to the state are, in the end, likely to have a more powerful effect on life in China.

Although some argue that the way to support human rights is to refuse trade with China, this punishes precisely those who are most likely to change the system. Put bluntly, Li Peng and the Chinese conservatives want to continue to run the economy by state fiat. Of course, there should be tight export controls on the transfer of militarily sensitive technology to China. But trade in general can open up the Chinese economy and, ultimately, its politics too. This view requires faith in the power of markets and economic freedom to drive political change, but it is a faith confirmed by experiences around the globe.

Even if there is an argument for economic interaction with Beijing, China is still a potential threat to stability in the Asia-Pacific region. Its military power is currently no match for that of the United States. But that condition is not necessarily permanent. What we do know is that China is a great power with unresolved vital interests, particularly concerning Taiwan and the South China Sea. China resents the role of the United States in the Asia-Pacific region. This means that China is not a “status quo” power but one that would like to alter Asia’s balance of power in its own favor. That alone makes it a strategic competitor, not the “strategic partner” the Clinton administration once called it. Add to this China’s record of cooperation with Iran and Pakistan in the proliferation of ballistic-missile technology, and the security problem is obvious. China will do what it can to enhance its position, whether by stealing nuclear secrets or by trying to intimidate Taiwan.

China’s success in controlling the balance of power depends in large part on America’s reaction to the challenge. The United States must deepen its cooperation with Japan and South Korea and maintain its commitment to a robust military presence in the region. It should pay closer attention to India’s role in the regional balance. There is a strong tendency conceptually to connect India with Pakistan and to think only of Kashmir or the nuclear competition between the two states. But India is an element in China’s calculation, and it should be in America’s, too. India is not a great power yet, but it has the potential to emerge as one.

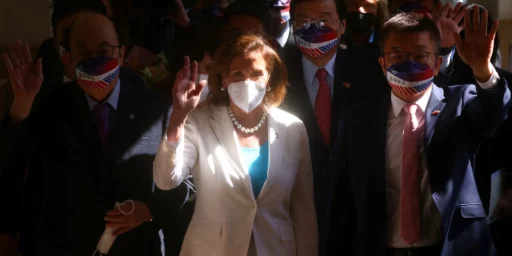

The United States also has a deep interest in the security of Taiwan. It is a model of democratic and market-oriented development, and it invests significantly in the mainland’s economy. The longstanding U.S. commitment to a “one-China” policy that leaves to a future date the resolution of the relationship between Taipei and Beijing is wise. But that policy requires that neither side challenge the status quo and that Beijing, as the more powerful actor, renounce the use of force. U.S. resolve anchors this policy. The Clinton administration tilted toward Beijing, when, for instance, it used China’s formulation of the “three no’s” during the president’s trip there. Taiwan has been looking for attention and reassurance ever since. If the United States is resolute, peace can be maintained in the Taiwan Strait until a political settlement on democratic terms is available.

Some things take time. U.S. policy toward China requires nuance and balance. It is important to promote China’s internal transition through economic interaction while containing Chinese power and security ambitions. Cooperation should be pursued, but we should never be afraid to confront Beijing when our interests collide.

All of this is true. And none of it is particularly belligerent.

If the Republicans were trying to create a China bogeyman for exploitation in 2000, they did a lousy job.

Neither Matt or Fukuyama claim it was a secret plot by “Republicans.” They specifically say it was “Bill Kristol and his circle,” i.e., the neocons, trying to influence what they considered to be a listless GOP in the 90s (they actually preferred McCain to Bush), and then from within as an influential faction in administration centered around Cheney (who saw the neocons as a means of pursuing reassertion of executive authority and hawkish, hardball foreign policy). After 9/11, they offered up their ready-made neo-Wilsonian ideology and rhetoric. Old skool realists Powell and Rice resisted, but the neocons were better prepared, better organized, and more determined.

It’s no secret that “national greatness conservatives” were looking for an enemy – any enemy – to give the country “purpose” all through the 90s, including China. The libertarians noticed, and were postitively apoplectic, because they saw it as Trotskyism in conservative clothing.

Oh, and “Dissident President?” How Trotskyite is that?

Andy, you’re only the second blog commenter I’ve seen compare neoconservatives to Trotskyites.

And yet terrorism was not an issue in the 2000 campaign at all and the GOP platform didn’t even mention it as an issue.

Rick, they made President Clinton the enemy, and were determined to be all things anti-Clinton. Thus when Clinton told them Al Qaeda should be their highest priority, they instead did the opposite and ignored Al Qaeda until it was too late. Watch the blogginheads segment.