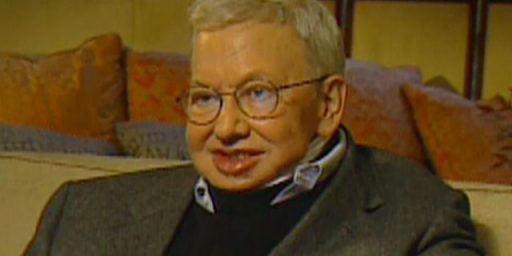

Roger Ebert: Grade Inflater?

The answer to the following question, in my humble opinion, is “yes”:

Thumbstruck: Is Roger Ebert a Little Too Kind? (TimeOut Chicago)

There’s no doubt that Ebert still loves movies, which is admirable given that he’s reviewed more than 5,200 of them over the past 38 years. But maybe he loves them too much. Consider his recent double take on the lame Adam Sandler remake of The Longest Yard. Ebert gave the movie a “thumbs up” on TV, but then second-guessed himself after spending a week at the Cannes Film Festival. “I can hardly bring myself to return to The Longest Yard at all, since it represents such a limited idea of what a movie can be and what movies are for,” he wrote. Fair enough. But then—and this is what bugs us—he still gave the movie three stars on the wishy-washy grounds that it “more or less achieves what most of the people attending it will expect.”

Granted, Ebert usually reserves four stars for genuinely outstanding movies, except when he lets special effects cloud his judgment, as in the case of The Cell (“One of the best films of the year”) or Dark City (“a triumph of art and imagination”). But he’s downright promiscuous with the three-star rating, awarding it to almost a third of the movies he reviews.

To be fair, Ebert has a reasonable, if almost existentialist, explanation for his grading system:

Movie Answer Man, May 25, 2005 (Chicago Sun-Times)

Star ratings are the bane of my existence, because I consider them to be relative and yet by their nature, they seem to be absolute.

Ebert’s problem is that he tries too hard to adapt his review to the movie. With a summer blockbuster, he gives the benefit of the doubt, recognizing that mindless entertainment rules the season. With a presumed Oscar contender, he elevates the standards. I think that critics should certainly bear in mind the aim of a movie and have, as it were, a sense of humor. But they should also remember that, with such an approach, they run the risk of being terribly sloppy. And, within a span of hundreds of movies a year, the inconsistencies will become abundantly clear — very quickly.

Except for Ebert, most of the critics on my reading list (A.O. Scott of the New York Times, Kenneth Turan of the Los Angeles Times, and David Denby of the New Yorker, among others) don’t use ratings, and I tend to prefer it that way. I like going through an entire review without the distraction of, and the temptation to rely solely on, a grade. Sure, I visit Rotten Tomatoes, too. But I use it mainly as a tool to find fresh perspectives and always with the understanding that the numbers are flawed. In any event, it’s much more satisfying to take in a full deconstruction of a movie and understand all of the nuances.

Man, that’s a lot of work – I just watch the trailers and see if there are mostly nekkid hot chicks in the flick before I plunk down my $.

Actually, I quite like about Ebert that he judges movies for what they are. There’s nothing I hate more than reading or listening to reviews by the likes of David Edelstein (whom I consider to be the worst offender on this count) and others who fault what is nothing more than a dumbly entertaining action movie for failing to make deep and moving commentary on the human condition. I seem to remember Ebert once calling Star Wars something like shallow space opera. He is right. He is also right that for shallow space opera, Star Wars is fairly good.

I commented on Ebert’s grade inflation a while back. For a stretch, more than 80% of the movies he rated had three stars or more.

Once upon a time, people enjoyed going to the movies, enjoyed them for what they were and knew better than to take them too seriously. But as the years went by, the people gradually became spoiled by the industry and they became less satisfied with the movie-going experience. The movies, in fact, had steadily improved over time, become more elaborate and extravagant every year, but the better they got, the less people were impressed. Then the internet came, and the all the worst traits of man were expressed there from the safety of their anonymity, and then the vile epithets were multiplied a thousandfold until there was scarcely a site anywhere where the inevitable “this movie sucked” couldn’t be found. They began to imagine a golden age of the past where all the classic movies were great, each the pinnacle of writing, acting, and directing. Sadly this golden age never existed except in the minds of those who so urgently longed for it.

Somewhere along the line, man had lost his capacity to say “this is not my kind of movie”, and emulating those staples of WGN television, began to perform a Siskel and Ebert routine. Like those two critics, they merely expressed an opinion without the benefit of in-depth knowledge of the film-making process. Almost overnight across the entire internet, the entire online population became knowledgeable about writing, acting, directing, etc. More knowledgeable, it would seem, than Hollywood itself, though in the realm of amateur film-making, most of these individuals were strangely absent. More importantly, the ability to objectively critique a movie never existed in them, and instead was replaced by an urgent need to foist one’s favorite movies on others. Which is where we find ourselves now. Drowning amidst a sea of pretentious, would-be experts, who, thanks to the internet, are free to broadcast their mindless blather to all points on the globe.